forum

library

tutorial

contact

Crapo Tries to Bridge Salmon Divide

by Rocky BarkerThe Idaho Statesman, October 19, 2003

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Crapo Tries to Bridge Salmon Divideby Rocky BarkerThe Idaho Statesman, October 19, 2003 |

Water users, fish activists weigh senator’s offer

For Barb Lane of Riggins and Vickie Purdy of Eagle, the debate over Idaho salmon and water is larger than economics, science or politics.

For Barb Lane of Riggins and Vickie Purdy of Eagle, the debate over Idaho salmon and water is larger than economics, science or politics.

Lane, who with her husband, Gary, operates Wapiti Outfitters, has built her life around salmon and steelhead. Purdy, who with her husband, Dana, owns a 129-acre dairy farm near Eagle, sees their Boise River irrigation water as a sacred right.

Like other water users and salmon advocates, they face tough decisions as they ponder Republican Sen. Mike Crapo´s evolving offer to find a collaborative resolution to the Pacific Northwest´s most intractable environmental debate.

For Salmon advocates, the question is whether to shift strategies and weaken their legal position in exchange for intangible and still-unclear commitments from Crapo and federal dam operators.

For farmers, canal companies and other Idaho water users, it´s a matter of sitting down with people they believe seek to drive them out of existence.

“All these years we´ve given and given, and they´ve taken and taken,” Purdy said. “Enough is enough.”

Crapo, a stalwart defender of Idaho water, isn´t asking salmon advocates to give up their goal of breaching the four lower Snake River dams, which they blame for the decline in native fish runs. Neither is the senator, an opponent of breaching, asking water users to give up their control of Idaho water.

Crapo is asking for something even tougher: that each side trust him — and each other — in the search for a solution.

“What we are seeking to do is to find the common ground where neither side is going to have a total victory or an eradication of the other side´s interest,” Crapo said.

Crapo’s challenge

His biggest challenge is creating a forum that has relevance beyond Idaho´s borders. For more than a decade, the Pacific Northwest´s salmon debate has revolved around Idaho´s salmon because they have the longest migration and the most dams to pass between spawning grounds and the Pacific.

But the debate is regional, national and even international. The Northwest´s federal hydroelectric system produces 60 percent of the power generated in Idaho, Washington, Oregon and Montana. The $9 billion Pacific Northwest agriculture economy is largely tied to irrigation from the Columbia and Snake river systems.

Anglers in Washington, Oregon, Alaska and British Columbia all catch Idaho salmon. And the federal government is picking up a huge chunk of the bill for the salmon recovery program that has been in place since 2000.

The national scope of the debate is evident, considering 118 members of Congress from both political parties sent a letter to President Bush last week asking him to consider all options for recovering Pacific Northwest salmon, including buying more Idaho water and breaching four dams on the Snake River in Washington.

The letter angered Idaho water users not because it raises the issue of dam-breaching, but because it focuses on an issue even more threatening to their economy, heritage and power: It specifically targets Idaho water. The letter suggested the federal government buy more water from Idaho and Canada to increase flows to aid salmon migration through the Snake and Columbia rivers.

“If this letter from the liberal, largely Eastern bloc of congressmen is any indication of the environmentalists´ intentions, we´re in for quite a fight,” said Norm Semanko, president of the Coalition for Idaho Water, which represents a broad cross-section of Idaho business, farm and water development groups.

The letter, signed by 12 Republicans, including conservatives like Reps. Tom Petri and James Sensenbrenner of Wisconsin and James Leach of Iowa, called for considering all options as a way of reducing wasteful spending.

“As carried out now, the effort´s ineffective,” Petri said. “If it were fully funded to make it as effective as possible, it would cost $1 billion a year. Either way, we have to consider different approaches.”

Pat Ford of Boise is executive director of Save Our Wild Salmon, a coalition of 54 regional and national groups representing anglers, conservationists, commercial fishermen and fishing-related businesses. His coalition sees breaching the four dams as the only way to save the Snake River´s wild salmon.

“The water users are mad because people around the nation care about Columbia-Snake salmon,” Ford said. “I say get used to it.”

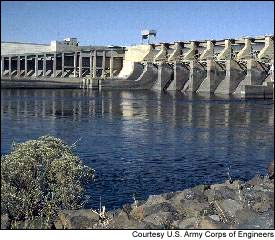

Sen. Larry Craig, R-Idaho, said the Pacific Northwest has a positive message to send to the nation, and it´s the same message President Bush sent when he visited Ice Harbor Dam in August.

“The story really ought to be written that our program is working, that the fish are returning in record numbers,” Craig said.

Lives on land and water

Barb Lane´s business has benefited from the dramatic increase in returns of salmon and steelhead. But she knows the fish they catch are largely hatchery-raised salmon that would swim back into the hatchery and not spawn in the Salmon River drainage where she and her husband make their home.

“The wild fish are where your gene pool comes from,” she said. “A lot of people don´t understand the importance of saving the wild fish as opposed to saying we have tons of fish coming back.”

Her husband, Gary, spends nearly every day on the river as a guide. They live in a tepee along the river in the summer. In September, they were married in a ceremony in boats on the river.

“Our lifestyle is tied to the river,” she said. “We are all connected to nature. A lot of people have gotten away from that because their priorities aren´t the same.”

Purdy´s priorities are remarkably similar. She and her husband, Dana, have roots deep in the land long farmed by Dana´s family. Each day, twice a day, they milk and feed the cows. They care for the calves. They grow corn and hay in fields that were once desert.

“It´s hard work and sweat,” Purdy said. “It´s exhilarating.”

Idaho water users say any discussion of the use of Idaho water for improving salmon flows must be on a willing-seller, willing-buyer basis. That doesn´t mean farmers like Purdy are ready to sell to the highest bidder, especially if the water goes to increase flows for salmon.

“I would be taking that money at the cost of the destruction of my family, my farm, my cattle,” she said.

“That is not how I want to see my water used. It would be a terrible waste and immoral in my opinion.”

Salmon aren´t the only threat to their water and lifestyle. Just last week, farmers in California were forced to accept a compromise that allowed the city of San Diego to buy water from them for $280 an acre-foot. An acre-foot of water is 326,000 gallons, enough to supply two families for a year.

“We are a growing state,” Craig said. “For that growth to continue we will need water. The great debate in Idaho is going to be dividing the water between human uses, let alone the wildlife.”

Competing visions

Craig represents the view of the coalition of groups — from Idaho farmers to Portland port authorities to regionwide utilities — opposed to breaching dams, buying additional water to increase flows, and aiding fish passage by increasing the spill of dammed-up water that could run through hydroelectric turbines.

“I don´t think we have to make trade-offs,” Craig said. “I think we have to bring balance.”

Buying water, increasing spills and other hard choices are a part of the federal salmon plan approved in 2000 and supported by the governors of Washington, Idaho, Montana and Oregon. If these measures don´t work by 2008, then the plan called for reconsidering breaching the four Snake River dams in Washington. Salmon advocates and the state of Oregon challenged the federal plan, saying it had no way of measuring whether the dam operators and others were doing what they promised.

A federal judge agreed in May. The federal agencies have until June to rewrite the plan.

“Our strategy is to use various tools including litigation to force the federal government to honor its plan,” said Ford. “It´s not about forcing the region to do anything. It´s about forcing the federal government to honestly implement the plan.”

In the early 1990s, Oregon Sen. Mark Hatfield brought together industry, conservation groups, Indian tribes, states and federal agencies for wide-ranging talks aimed at writing a salmon plan for the region.

Though progress was made, the talks broke down largely along the fault lines that exist today. Some other efforts to bring various groups together have borne some fruit. More recently, the Citizens Economic & Fish Recovery Forum has brought together farm, industry groups and the Umatilla Tribe in Oregon to seek salmon solutions short of breaching dams.

But its approach presents a direct challenge to the salmon advocates´ agenda. For collaboration to work, Crapo said, people on both sides need to be convinced to move away from the traditional winner-take-all approach inherent in the current salmon decision-making process.

“It forces people to seek alliances and take positions that are very rigid and to seek alliances that will support those rigid positions,” Crapo said. “When you bring people together, once the process is sufficiently validated ... instead of it being win-lose, we can move to win-win.”

Lane doesn´t know how all the politics stack up, she said. But she likes Crapo´s approach.

“I definitely think communication is an important part of getting things worked out,” she said.

“I think people should discuss what´s going on without putting blinders on.”

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum