forum

library

tutorial

contact

Strong Sockeye Run Bodes Well

for Snake River Returns

by Eric Barker

Lewiston Tribune, July 8, 2022

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Strong Sockeye Run Bodes Well

by Eric Barker

|

In 2015, a year that looked promising for sockeye, more than

4,000 Idaho-bound redfish were counted at Bonneville Dam

This summer, Idaho's Stanley Basin could see the most robust return of sockeye salmon it has in several years.

This summer, Idaho's Stanley Basin could see the most robust return of sockeye salmon it has in several years.

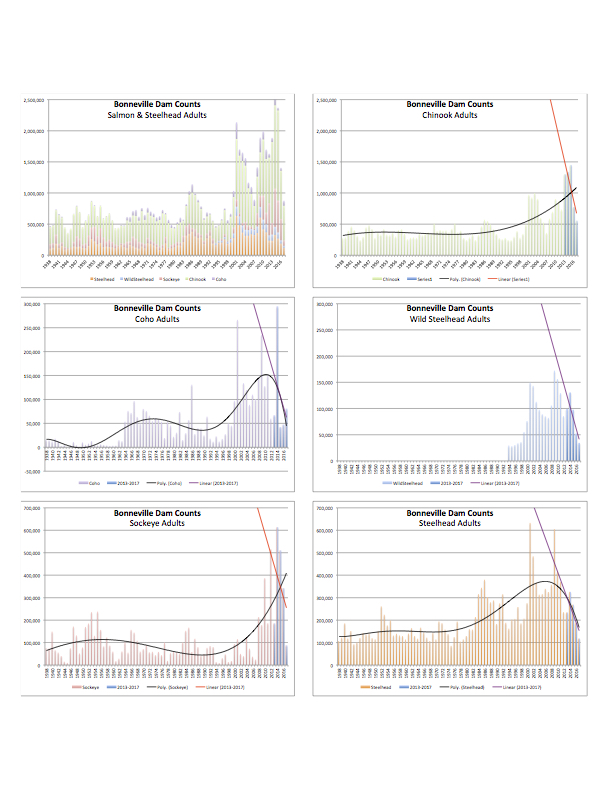

Sockeye numbers at Bonne-ville Dam on the Columbia River have surged in recent weeks, smashing preseason forecasts and providing unexpected fisheries from below the dam to the river's upper reaches. More than 56,000 were counted on June 27 alone and, as of Monday, the total run had topped 500,000.

But almost none of those will come anywhere near Idaho or the Stanley Basin. Instead, just a tiny fraction of the steady stream of reds counted at Bonneville Dam, perhaps as many as 1,800, will peel off near the Tri-Cities and venture up the Snake River. But it's still a big deal.

Snake River sockeye are the most imperiled salmon in the Columbia Basin. They've been hanging by a thread for decades and exist today only because of an emergency captive brood program hatched in the 1990s.

Just like all of the Snake River's wild salmon runs protected by the Endangered Species Act, sockeye have had a rough half a decade. Poor ocean conditions, layered on top of high water temperatures, dam-caused mortality and predators, have hammered returns. It started in 2015, a year that looked promising for sockeye. More than 4,000 Idaho-bound redfish were counted at Bonneville Dam that year. But an unprecedented combination of low flows and scorching weather caused the Snake and Columbia rivers to overheat. Biologists estimated about 90% of the Snake River sockeye succumbed to water temperatures in the 70s.

That same year, a mass of warm water nicknamed "the Blob" formed off the coasts of Oregon, Washington and British Columbia. It lingered into 2016 and ushered in a string of years in which the northern Pacific Ocean experienced elevated sea surface temperatures and a dearth of upwelling that fuels the bottom of the food chain.

Salmon and steelhead suffered. But that cycle finally broke and 2021 was among the most productive for salmon and steelhead recorded over the past two decades. Salmon species appear to have benefited, including sockeye.

"It's 100% ocean," said Eric Johnson, a sockeye specialist with the Idaho Department of Fish and Game. "Everything seems to be responding a little bit better. Our chinook runs are up, our steelhead runs are up. It wasn't a surprise our sockeye numbers are up as well."

As of Monday, 127 of the half a million sockeye counted at Bonneville Dam were detected carrying tracking tags indicating they started life in Idaho. Only a portion of juvenile sockeye salmon are implanted with tags. Expand the numbers and it means about 2,800 Snake River sockeye have or will pass Bonneville Dam this year. Bonneville is the first of eight big dams the fish must negotiate.

If they experience average survival, about 1,600 to 1,700 will make it to Lower Granite Dam on the Snake River -- the eighth dam in the gauntlet. But they will still have hundreds of miles to swim and another 40% can be expected to succumb, leaving about 1,000 to survive the 900-mile trip from the ocean to the Stanley Basin, the headwaters of the Salmon River.

It would be the best return since about 1,500 sockeye made the journey in 2014 and a welcome one-year trend for those trying to save the fish.

But the job is far from done. There have been incremental leaps forward in previous years and serious setbacks as well.

Only 23 sockeye returned to the Stanley Basin in the 1990s, which included two years when no fish made the journey. The fish were listed as endangered in 1991. The next year, only a single male adult sockeye returned to Idaho. He was given the name Lonesome Larry and became part of a desperate effort to save the fish.

Idaho, the Shoshone-Bannock Tribe and the federal government had started a hatchery brood program. Lonesome Larry and other sockeye that made the trip were no longer allowed to spawn in the wild. Instead, they were captured and spawned in a hatchery. Most of their offspring spent their entire lives in captivity. Slowly, as numbers built in the captive brood program, more and more juvenile sockeye were released and allowed to migrate to the ocean. Eventually, some adults were allowed to spawn in Redfish, Pettit and Alturas lakes -- cold, clear water catchments at the base of Idaho's famed Sawtooth Mountain Range.

In 2013, Idaho opened Springfield Hatchery dedicated to sockeye and with a goal of releasing 1 million smolts each year. A problem with water hardness led to low smolt survival rates for the first few years of the program. Then came the string of poor ocean conditions.

Could the fish one day provide the type of fishery that happens on the Columbia River? That's the goal, but it remains distant, and sockeye continue to swim near the brink of extinction.

But those on their way to the Sawtooth Valley look like they will have good conditions.

"I don't anticipate any issues," Johnson said. "Water temperatures are really low, really cool compared to what they normally are. We are kind of getting to the average (air) temperatures right now for summer, so I think unless things really heat up and change, I wouldn't expect anything different than average (survival)."

Related Pages:

Count the Fish Idaho Fish & Game (1977-2021)

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum