forum

library

tutorial

contact

40 Years After Creation, Northwest

Power and Conservation Council at a Crossroads

by Tom Karier

The Oregonian, December 15, 2019

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

40 Years After Creation, Northwest

by Tom Karier

|

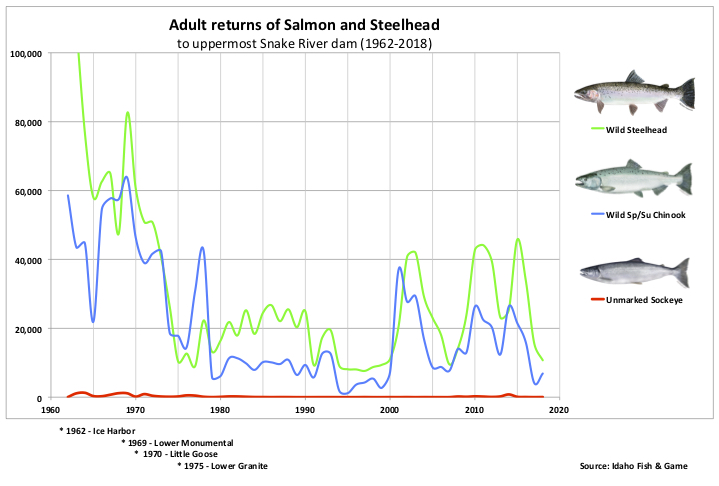

The Northwest is not winning the battle to save wild salmon and steelhead in the Columbia River. Although most of the 12 listed salmonid stocks in the basin demonstrated a weak upward trend for a couple decades, that progress has stalled. Total returns of salmon and steelhead passing Bonneville Dam last year slipped to the second-lowest level in the past 18 years, and spring Chinook returns were 60 percent of the 10-year average. This year, they were only 37 percent.

The Northwest is not winning the battle to save wild salmon and steelhead in the Columbia River. Although most of the 12 listed salmonid stocks in the basin demonstrated a weak upward trend for a couple decades, that progress has stalled. Total returns of salmon and steelhead passing Bonneville Dam last year slipped to the second-lowest level in the past 18 years, and spring Chinook returns were 60 percent of the 10-year average. This year, they were only 37 percent.

Everyone agrees that part of the decline can be blamed on ocean conditions. But is it too much to expect some sign of progress from Bonneville's fish and wildlife efforts that now exceed a cumulative cost of $15 billion over 40 years?

After 20 years representing Washington state on the Northwest Power and Conservation Council, I no longer expect Bonneville to save wild salmon and steelhead. Here's why.

The first reason is the Bonneville Power Administration. Its idea of a salmon recovery program is to give states and tribes hundreds of millions of dollars in exchange for pledging to not sue Bonneville in federal court. However, as recent fish returns demonstrate, refraining from suing Bonneville doesn't necessarily produce more salmon. It also doesn't guarantee success in court as Bonneville continues to lose in the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, casting suspicion on the basic strategy. These deals -- memorialized in the Columbia Basin Fish Accords signed in 2008 by three federal agencies, three states and seven tribes -- are posted on Bonneville's website.

Alternatively, Bonneville could have taken its role seriously as manager of the largest recovery program in the nation. It could have included performance goals in its fish contracts requiring actual results, such as more fish for harvest, more fish on spawning grounds and higher levels of productivity in restored habitat. Instead, Bonneville chose to require legal compliance rather than biological outcomes. It may have been easier as a power marketing agency to buy friends than performance, but it may not have been better for fish.

The second problem is that Bonneville's budget priorities reflect political compromises rather than fish priorities. Most of Bonneville's money is spent on overhead, planning, studies, contracting, coordination, research, monitoring and evaluation. Precious few dollars flow into on-the-ground projects that have any hope of saving salmon. Research and monitoring, for example, have accounted for as much as 40 percent of Bonneville's entire fish budget. Some of this is necessary, but most of it takes money from high-priority actions such as restoring floodplains, protecting cool-water refuges, removing culverts, protecting water flows and creating the type of habitat and safe passage that salmon need.

Forty years ago, the Northwest faced a serious problem: Bonneville Power Administration, a federal power marketing agency, was leading Northwest utilities down the road to financial ruin and a natural-resource disaster. Bonneville was planning to build five nuclear power plants and was failing to take responsibility for collapsing salmon runs, which were struggling to survive due to the same dams that provided Bonneville power to sell.

Congress had a bold solution. It created a council, now called the Northwest Power and Conservation Council, with representatives from Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana. The 1980 Northwest Power Act granted the council the responsibility and authority to ensure that Bonneville would save salmon and make smarter investments in energy resources.

I had the honor of representing Washington state on the council for 20 years which included multiple appointments by Govs. Gary Locke, Chris Gregoire and Jay Inslee.

The council’s role in power planning remains as critical today as it was in 1980. The emergence of regional markets, climate change, carbon reduction, renewables generation, energy efficiency, and smart grid technologies have made long term regional planning for electrical power more important and considerably more complex than it was 40 years ago.

The council’s power plans continue to guide the region in the direction of clean, adequate and reliable power and energy efficiency that saves Northwest ratepayers hundreds of millions of dollars per year.

Unfortunately, the council’s fish and wildlife planning hasn’t seen the same success. Although Congress envisioned that the council would design the program for fish and wildlife recovery, the council ceded most of its original responsibilities to federal agencies over the past 20 years. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration captured part of that responsibility when it started listing species of salmon and steelhead in the Columbia Basin as threatened and endangered. Because the federal Columbia River power system adversely affected these fish populations, NOAA developed a plan, called a biological opinion, that directs Bonneville and other federal agencies to implement specific actions to avoid the extinction of these species.

As a result, project sponsors lobbied NOAA to include their projects in these biological opinions, which essentially guaranteed Bonneville funding. In a questionable act of self-interest, NOAA even wrote its own research projects into these plans and collected tens of millions of Bonneville ratepayer dollars for its science center in Seattle. One of these projects was supposed to evaluate the benefits of habitat restoration but failed to produce compelling results after spending more than $75 million over 15 years.

And how are these federal agencies doing in helping salmon recover? Adult returns for endangered salmon and steelhead are among the lowest of the last two decades including Snake River steelhead which just dropped below a critical threshold for survival.

Eleven years ago, Bonneville decided to bypass the council altogether with its Columbia Basin Fish Accords. Bonneville negotiated agreements with individual states and tribes promising long-term funding for projects in exchange for committing not to sue Bonneville over its fish and wildlife strategies. As Bonneville implemented the accords and biological opinions, the agency made clear it expected compliance, not challenges from the states and the council. How could the council object when three of the four states were signatories to the accords?

Sidestepping the council has been lucrative for some of Bonneville’s partners. Idaho, primarily through its Department of Fish and Game, led the way in capturing more Bonneville fish and wildlife funds than agencies in other states. Idaho had learned the lesson that if they squeezed a million dollars out of Bonneville, Washington and Oregon ratepayers would pay 90 percent compared to only 5 percent from Idaho ratepayers. Bonneville had a choice between providing the funding and winning Idaho support or answering to a strong Republican Congressional delegation and the threat of lawsuits. It was not a difficult choice.

Due to bureaucratic inertia, the council continues to go through the motion of conducting program reviews and occasionally issues a project recommendation – but typically this only happens after the project secures Bonneville approval.

Congress’ vision that four Northwest states could save salmon and steelhead by exercising authority over Bonneville and other federal agencies has run its course. Bonneville is back in charge and has yet to show substantive progress from its expensive salmon recovery effort that has cost ratepayers over $16 billion. Threatened and endangered salmonid populations are crashing.

Who will oversee Bonneville and ensure that it spends ratepayer money efficiently and effectively? Who will make the tough decisions about which salmon recovery efforts are succeeding and which ones are failing? That question was supposed to have been settled 40 years ago with the passage of the Power Act, but it remains open today.

Related Pages:

Why Bonneville Can't Save Salmon by Tom Karier, Spokesman Review, 8/18/19

Dam Breaching Isn't So Simple by Tom Karier, The Oregonian, 7/12/19

Two Long-Serving Members of NW Power/ Conservation Council -- Karier, Booth -- Retire by Staff, Columbia Basin Bulletin, 1/11/19

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum