the film

forum

library

tutorial

contact

|

|

Salmon Face Deadly Hot Waters Along Columbia

and Snake Rivers as the Call for Dam Removal Grows

by Samantha Wohlfeil

Pacific Northwest Inlander, September 2, 2021

|

A complex web of ecosystems and economic drivers depends on the river systems that flow from cool Inland Northwest elevations on out to sea.

A complex web of ecosystems and economic drivers depends on the river systems that flow from cool Inland Northwest elevations on out to sea.

Farmers use Snake River dam reservoirs to enable barging of their grains from as far inland as Lewiston, Idaho. Native American tribes that could once rely on abundant fish runs worry about their future and that of wolves, grizzly bears, trees and other parts of nature that historically received nutrients from fish that now struggle to survive.

Salmon and steelhead rely on the cool mountain waters of spring to usher them out through the Snake and lower Columbia River to the sea, where commercial fishermen and guides depend on their return years later.

The adult fish need those same upriver waters to provide a cool refuge for spawning when they return to their home grounds in the spring, summer or fall.

But the window of survivability is getting shorter and shorter for those already endangered fish as climate change and placid waters slowed by eight different dams create warmer and deadlier conditions.

Anadromous fish -- those that switch between fresh and saltwater -- struggle in water that's hotter than 68 degrees Fahrenheit, and at 70 degrees they start to die. This summer, water behind all eight dams on the lower Columbia and Snake rivers hit that mark, with some getting as high as 73 degrees.

The effects are being felt everywhere.

Bob Rees has been a professional fishing guide in Oregon for 25 years. Speaking from his boat outside Astoria in late August, he notes that spring Chinook, prized for their quality and high price at market, used to return to the rivers in early spring, spending summers there before spawning at their home grounds in September.

"Typically they run in April and May into Portland and even Idaho, but we're catching them in August because they know they can't survive up in those hotter watersheds," Rees says between catching fish with customers on his guide boat. "So they're holding down here where the estuary is cooler."

Along the Deschutes River, a cold water refuge from the lower Columbia, fly fishing guides Alysia and Elke Littleleaf say they've seen the changes over the years, too.

Descendants of the Wasco Tribe of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, the couple has not only seen hotter river temperatures and restrictions affect fishing times but also algae blooms that impact the tribe's freshwater resources. Personally, they've switched to gathering their own natural spring water as those issues continue impacting them.

"We know the feeling of climate change," Elke Littleleaf says. "We see the fish getting smaller, the diseases they're facing, and it's not just in our river. It's scary times."

The time has come to plan with people in floodplains for dam breaching that can help fish runs recover, Alysia Littleleaf says.

"This 'hurry and wait' scenario, we're tired of hearing that. As Native people we hear that too much," Alysia Littleleaf says. "It's time to honor the treaties. It's too late, almost."

For 20 years, the public has heard that salmon and steelhead could be helped by breaching the four lower Snake River dams. Now, with several species in crisis, many worry there aren't another 20 years to prevent them from becoming memories. But the question remains, who will take the lead?

VIGIL FOR THE DEAD AND DYING

The overall picture for 2021 isn't complete yet, but hot water exacerbated by a historic heat wave has harmed some of the more than one dozen endangered fish species along the Columbia and Snake rivers.

Northwest tribes and environmental groups worried this year could be a repeat of 2015, when the region saw more than a quarter million sockeye salmon die off.

In late June, air temperatures in parts of the Pacific Northwest hit as high as 116 degrees, which was deadly for hundreds of people. With the heat rapidly melting the remaining mountain snowpack that would usually keep rivers cool later into the summer, water temperatures also rose.

In weekly reports, environmental groups have tracked reservoir temperatures. All four Snake River dams had waters above 68 degrees for at least 39 to 60 days this year as of Aug. 24; the four lower Columbia River dams saw temperatures exceeding 68 for at least 58 to 60 days this year.

On Aug. 19, the water behind Ice Harbor Dam on the Snake River hit more than 73 degrees, while water behind the Columbia River's John Day Dam hit 72.5 degrees.

But the stress on salmon was evident well before that.

July footage captured for the environmental group Columbia Riverkeeper showed sockeye sick with lesions and infections as they sought refuge and died in the Little White Salmon River.

On July 30, Native American tribes and environmental groups held a vigil for the fish.

"What do I tell my grandchildren? How do you continue to give hope for the future?" said Cathy Sampson-Kruse, a member of the Confederated Tribes of Umatilla Indian Reservation and a Columbia Riverkeeper board member, speaking in a speech for the vigil. "We carry on the best we can, but we are now at a precipice."

'WE, THE PEOPLE'

Since time immemorial the Nez Perce Tribe has honored the connections between salmon and other animals. The tribe's traditional territory includes much of the Palouse, from north of Pullman to south of Lewiston and beyond.

But compared to local stories of runs so abundant you could practically walk across the river, very few fish now return to the cool tributaries of the Clearwater and Salmon rivers in north central Idaho.

This May, the tribe's fisheries resources staff pointed out just how dire things are in a presentation to the Northwest Power and Conservation Council. The council develops a regional power plan for Idaho, Washington, Montana and Oregon.

This May, the tribe's fisheries resources staff pointed out just how dire things are in a presentation to the Northwest Power and Conservation Council. The council develops a regional power plan for Idaho, Washington, Montana and Oregon.

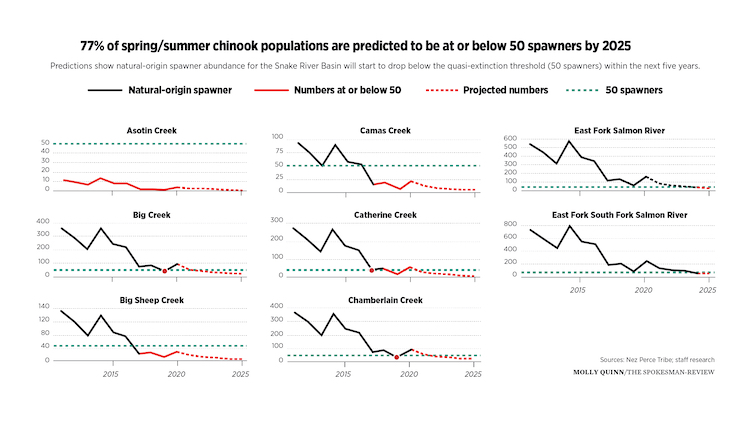

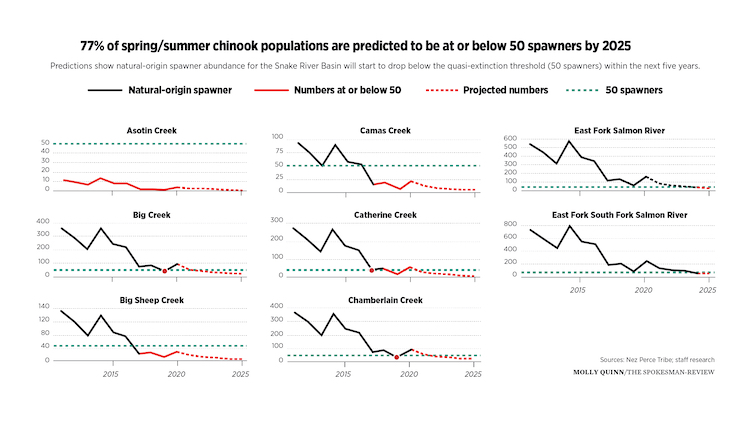

The presentation notes that while none of the runs are effectively extinct yet, 42 percent of spring and summer chinook runs in the Snake River are at a "quasi-extinction threshold" where 50 or fewer spawning fish are returning to 31 smaller creek areas. By 2025, just four years from now, national and state data point toward 77 percent of those 31 regions seeing fewer than 50 fish return.

"It just emphasizes the need to breach the lower four Snake River dams," says Elliott Moffett, a board member of Nimiipuu (the Nez Perce name for themselves) Protecting the Environment, a nonprofit that works on environmental restoration and education for youth. "They're just such pools of death for our fish."

One of the major issues politicians opposed to dam breaching often mention is that the reservoirs enable barging of grain and lumber all the way from Lewiston to the Pacific Ocean.

But Julian Matthews, a co-founding member of Nimiipuu Protecting the Environment, doesn't think people realize that the tribe and individual tribal members like him would also be impacted by farming changes.

"The tribe has a lot of land leased out to non-Indian farmers," Matthews says. "We also will be impacted by the changes to barging."

Tribal members who farm and tribal members who lease out their land in exchange for a share of that year's crop would both be affected by costs to ship that grain by another method to market, Matthews says.

But Matthews, Moffett and many others are trying to convey a sense of urgency to decision-makers as the fish can't wait for many more years of studies and negotiations.

"Someone has to take a stand," Moffett says. "We just need to get to the business at hand, which is breaching the four lower Snake dams, and we need the leadership to lead us that way."

Federal and state agencies have tried other methods of helping, including loading juvenile fish onto barges or trucks to take the trek downstream.

"We're putting fish on trucks so we can put wheat on the river," says Sam Mace, Inland Northwest director of Save Our Wild Salmon, with an air of disbelief. "Especially this year, with the backdrop of this summer and knowing that the fish have had a rough time, I think our senators and elected leaders are feeling that sense of urgency."

But everyone is waiting to see which elected leaders will take action, Mace says.

So far, one of the only congressmen to promote breaching the dams is U.S. Rep. Mike Simpson, a Republican from Idaho. But his plan has yet to receive support from congressional delegations in Washington and Oregon.

"We're all waiting to see, 'OK, what is your plan?'" Mace says. "We don't have 10 more years to figure this out."

Mace says for the fish to have the best chance, the region needs, in the next year, a plan for breaching, alternate methods for grain transportation and funding.

When looking at what true recovery would mean, fish and wildlife agencies look to the wild runs, not hatchery fish, says Stephen Pfeiffer, a conservation associate with Idaho Rivers United, which works to restore healthy fish runs.

"Our wild fish are on the threshold of extinction, and that's especially evident when you look at the last 60 years or so of collapse," Pfeiffer says. "The window is closing on these populations being able to withstand climate warming."

A key answer could lie right in the very central Idaho areas that have seen fish all but disappear. With higher elevation and cooler temperatures, several rivers in that area could provide the cool refuge anadromous fish need, so long as they can get there, Pfeiffer says.

"The environment of the mainstem Columbia and Snake rivers, exacerbated by the dams, is so inhospitable the concern is these fish won't be able to migrate back to Idaho," he says. "The good news is ... central Idaho, which still has this incredibly intact system of high elevation rivers and streams, is modeled to withstand a lot of the climate warming impacts."

Samantha Wohlfeil

Salmon Face Deadly Hot Waters Along Columbia and Snake Rivers as the Call for Dam Removal Grows

Pacific Northwest Inlander, September 2, 2021

See what you can learn

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum

A complex web of ecosystems and economic drivers depends on the river systems that flow from cool Inland Northwest elevations on out to sea.

A complex web of ecosystems and economic drivers depends on the river systems that flow from cool Inland Northwest elevations on out to sea.