forum

library

tutorial

contact

When It Comes To Dams,

Dugger's Claims are Fishy

by Richard Scully

Lewiston Tribune, September 20, 2022

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

When It Comes To Dams,

by Richard Scully

|

From 1938 to 1947, lower river harvest rates averaged 64% for chinook salmon and 60% for steelhead.

This Turnabout is a response to comments in Marvin Dugger's Aug. 28 commentary.

This Turnabout is a response to comments in Marvin Dugger's Aug. 28 commentary.

First, it has been possible to estimate salmon and steelhead harvest rates below Bonneville Dam since 1938. Those estimates are not "pure speculation."

The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife's "Status Report: Columbia River Fish Runs and Fisheries 1938-2000" states that: "The estimates of the size of the upriver (above Bonneville Dam) runs were obtained by adding the lower river (below Bonneville Dam) fish landings to the appropriate Bonneville Dam fish counts." Lower river landings divided by (lower river landings plus Bonneville Dam fish counts) equals harvest rate.

From 1938 to 1947, lower river harvest rates averaged 64% for chinook salmon and 60% for steelhead.

During the 1991-2000 decade, harvest rates below Bonneville Dam were only 5% for chinook and nearly zero for steelhead. Dugger referred to his friend, Charlie Pottenger, whose graph purported to show how fish populations on the Columbia and the Snake rivers were stable from the year 1938 until the year 2000.

But, as I stated before, "The reason Pottenger's graph was flat from 1938 through the end of the century was partially because harvest decreased at the same time total run size decreased, not because the number of fish remained the same."

The average 127,500 Bonneville Dam steelhead count from 1938-47 were all wild fish. Of the 227,300 average annual steelhead counts from 1991-2000, only 28,800 (13%) were listed as wild, and part of these "wild" or non-adipose fin clipped fish were likely unclipped hatchery fish. A 2019 Idaho Fish and Game study (Report No. 20-12), documented that at Lower Granite Dam, 30% of the non-adipose fin clipped steelhead were actually hatchery fish. Wild Snake River steelhead have remained threatened under the Endangered Species Act since 1997.

The increase in 21st century steelhead numbers were mostly hatchery fish. Only 28% at Bonneville Dam were unclipped "wild" fish, and part of these were likely hatchery fish.

Dugger noted that the number of wild steelhead counted at Bonneville Dam in the 2000-09 interval was 117,000, similar to the average of 127,000 steelhead from 1938-47. However, 60% of the steelhead entering the Columbia River in 1938-47 were harvested below the dam, whereas virtually no steelhead were harvested below Bonneville Dam in recent years. The average number of steelhead, all wild, destined to cross Bonneville Dam in the 1938-47 interval was actually near 317,000.

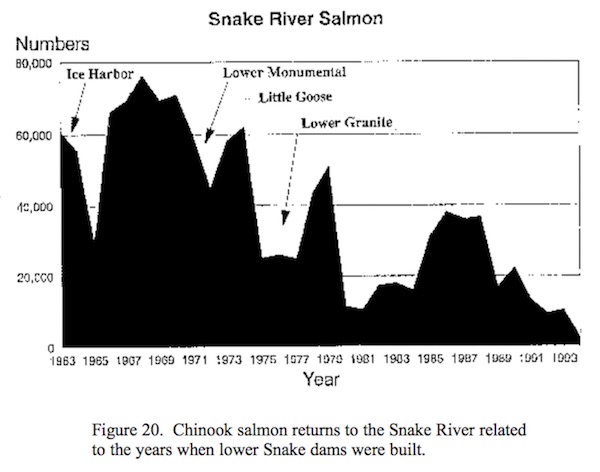

The abundance of salmon and steelhead was much greater from 2000-09 than in recent years due to variations in river and ocean conditions. Breaching the lower Snake River dams would increase the frequency of abundant fish runs as it would greatly decrease the time it takes smolts to reach the ocean and decrease the number of times a smolt encounters a dam's fish bypass system.

The Fish Passage Center documented that making these changes would significantly increase Snake River smolt survival.

Under most river conditions, smolts survive better if they are spilled over dams than if they enter bypass systems and get barged downriver. As I've noted previously, in the five years when there were fewer than 10,000 spring chinook adults counted at Lower Granite Dam, the average percentage of smolts that were barged two years earlier averaged 67%, while the average percentage of smolts barged two years prior to the seven years when adult spring chinook counts at Lower Granite dam exceeded 80,000 was only 57%.

A combination of factors contribute to the smolt-to-adult survival ratio.

The flex-spill program (16 hours of spill per day to benefit smolts and eight hours of minimum or no spill to maximize power generation) in effect since 2019 benefits smolt survival. But the relative benefit depends on which hours are chosen for power generation. If these are the same hours when a high percentage of smolts is moving past the dams, then smolt survival is reduced. And to some extent, that is what has been happening. Smolt survival would increase if fisheries managers could choose the hours for spill.

Another factor decreasing smolt survival recently is that dam operators have been holding some reservoir levels about 3 feet above the minimum operating pool (MOP). This is occurring in Lower Granite and John Day reservoirs.

Lower Granite is being held high because of the accumulating sediment near Lewiston-Clarkston, which makes it difficult to fill grain barges to capacity and to dock cruise ships at the Port of Clarkston.

John Day has been held above MOP to flood a potential piscivorous bird rookery on Blalock Island. The recommended river management plan would keep the reservoirs at MOP during the smolt migration season to decrease smolt travel time.

Unfortunately for fish, river managers are allowed to keep the reservoirs high when there are commercial navigation or other concerns.

Dugger asked: "If dams are the problem, why are there record numbers of sockeye that must cross nine Columbia River dams?"

There are also record numbers of sockeye in Bristol Bay, Alaska. Recent ocean conditions must have been favorable for sockeye. Sockeye are the only salmon species that spend at least one year in lakes before migrating to the ocean. Sockeye are genetically programed to find the outlet current in the otherwise still lake waters. This unique trait also helps them quickly move to the outlet of the Columbia River reservoirs.

Upper Columbia River sockeye are never barged and never enter a bypass system on the five upper Columbia River dams, as there are none. Spill greatly benefits out-migrating sockeye.

Washington Gov. Jay Inslee and Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash., declared recently that removing the four Lower Snake River dams was the most promising approach to salmon recovery, but that dam removal would not occur until services provided by the dams were replaced. Wind generators, solar panels and large-capacity batteries are part of the solution. So are restoring and modernizing rail lines and loading facilities and adding battery-electric locomotives with regenerative braking when hauling loaded grain cars down from the prairies.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum