forum

library

tutorial

contact

Fish Scales Break Even in 2020

by Eric BarkerBonner County Daily Bee, February 4, 2020

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Fish Scales Break Even in 2020by Eric BarkerBonner County Daily Bee, February 4, 2020 |

The long-term SAR for wild spring chinook from Lower Granite to Lower Granite is 0.92 percent and for wild steelhead it's 1.7 percent.

Adult returns of Snake River salmon and steelhead are the gold standard when measuring efforts to recover the imperiled fish. And by that standard, we don't have much gold.

Adult returns of Snake River salmon and steelhead are the gold standard when measuring efforts to recover the imperiled fish. And by that standard, we don't have much gold.

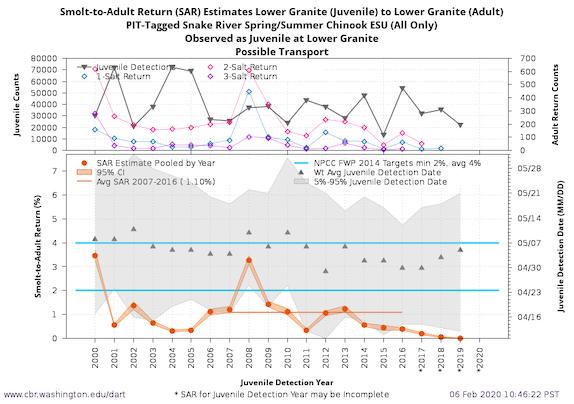

It's simple -- in order for the runs to persist, enough juveniles that migrate to the ocean must survive and ultimately return as adults to produce the same number of smolts to repeat the cycle. In the Snake River that means 2 percent of smolts must survive and return to spawn just for the runs to hold steady. To grow the runs, returns have to average 4 to 6 percent.

Thus the region has long held a goal of reaching smolt-to-adult return rates, or SARs, of 2 to 6 percent.

"It's established as the goal because the actual currency is adults coming back," said Michelle DeHart of the Fish Passage Center at Portland. "So smolt-to-adult captures the whole life cycle survival. You have a number of smolts going out and what number of adults coming back from that number of smolts is capturing everything that happened to those fish."

A return of 2 percent is basically breakeven. It's like making just enough money to cover your bills.

"Two percent is the lower end of the range, we would like to get considerably better than that," said Tim Copeland, a fisheries biologist for the Idaho Department of Fish and Game. "I've seen too many times people focus on that 2 percent as if it were the goal. It's not. The goal is to get something better than 2 percent on average."

To consistently build the runs, returns need to average 4 percent over time. In this scenario you make enough to cover your bills and sock a bit away in savings. A smolt-to-adult return rate of 6 percent means more savings and maybe even some discretionary spending cash.

Using that scenario, salmon and steelhead that return to the Snake River Basin are going broke. According to the Fish Passage Center, over the past 18 years the average smolt-to-adult return rate for wild Snake River spring and summer chinook is 1.26 percent. For wild Snake River steelhead it's a bit better. The 17-year average SAR for those fish is 2.37 percent.

The smolts are measured at Lower Granite Dam on the Snake River during their outmigration to the ocean. The adults are measured at Bonneville Dam during their return. If you measure the adults at Lower Granite Dam, the numbers are worse. For example, the long-term SAR for wild spring chinook from Lower Granite to Lower Granite is 0.92 percent and for wild steelhead it's 1.7 percent.

To DeHart, the problem is clearly the Snake and Columbia River hydrosystem. She said the declines of Snake River fish can be traced to completion of the four dams on the lower Snake River. For evidence she points to the long-running Comparative Survival Study. It looks at survival rates of several stocks of salmon and steelhead in the Columbia River basin. Fish that have to pass eight dams, four on the Columbia and four on the Snake, consistently fall below the 2- to 6-percent return rate.

However, fish that must pass fewer dams, usually hit the 2 to 6 percent sweet spot. On the John Day River in Oregon the SAR for wild chinook is 4.21 percent and 5.6 percent for wild steelhead. In the Yakima River the long-term SAR is 5.3 percent for steelhead and 3.3 percent for chinook.

"Most of the time they are in the 2- to 6-percent (range) and their averages are close to 4 percent. The John Day and Yakima rivers are meeting that goal most of the time," DeHart said.

"All of it is telling you, in terms of the Snake River, we went beyond the point of balance in development, we went too far."

She noted vast areas of the Snake River Basin, such as Middle Fork of the Salmon River in Idaho, contain pristine spawning and rearing habitat for the fish. The same is not true for the John Day and Yakima systems.

The John Day and Yakima rivers don't hit the 2- to 6-percent average every single year and there are some years where fish returning to the Snake River do hit the goal. For example in 2008, Snake River wild chinook and steelhead returned at a rate higher than 4 percent. But the same year the John Day fish topped 10 percent for steelhead and 6 percent for chinook and the Yakima River fish hit about 9 percent for chinook and steelhead.

Similarly, when return rates are poor the trends between the three rivers tend to track each other, only with the Snake River fish dipping much lower. For example, in 2015, an overall poor year for fish, the SAR for John Day steelhead was 1.7 percent and just more than 1 percent of chinook. For the Yakima River, steelhead posted an SAR of 1.5 percent in 2015 and chinook hit 2.5 percent. On the Snake River, the SAR was 0.35 percent for chinook and 0.2 percent for steelhead.

"It shows that fish that don't have to pass as many dams seem to have a better smolt-to-adult return rate consistently and those fish, at least up until recent years, were getting SARs in that 2- to 6-percent range," Copeland said.

The 2- to 6-percent goal was adopted by the Northwest Power and Conservation Council in 2003 and was pushed by fisheries managers at the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife and the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission. It was also folded into a state, tribal and federal science review panel examining causes and solutions to fish declines.

Distance the fish have to travel is another difference between Snake River runs and those that return to the John Day and Yakima rivers. Fish that return to the Snake River not only have to pass more dams they have to travel much farther both as juveniles and adults. But DeHart doesn't think it explains the low return rates for Snake River fish.

"You have to remember something, the distance from the mouth of the Salmon River (in Idaho) to the mouth of the Columbia River has not changed in thousands of years and those fish prior to the development of the hydro system still came out of the Salmon River. The difference is they returned in very big numbers."

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum