forum

library

tutorial

contact

EPA Issues Report Analyzing Heat

Pollution in Columbia, Snake Rivers

by George Plaven

Capital Press, June 2, 2020

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

EPA Issues Report Analyzing Heat

by George Plaven

|

Releasing water from Dworshak Reservoir, on the North Fork Clearwater River in Idaho,

as one example of what the agency is doing to cool water along the lower Snake River.

PORTLAND -- Oregon and Washington regulators are taking steps to address high water temperatures in the Columbia and Snake rivers that impact migrating salmon and steelhead.

PORTLAND -- Oregon and Washington regulators are taking steps to address high water temperatures in the Columbia and Snake rivers that impact migrating salmon and steelhead.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency issued a report May 18 that details when and where the two rivers become too warm for fish to survive -- especially at each of 14 federally operated dams spanning 900 river miles.

The report, known as a "Total Maximum Daily Load," or TMDL, typically studies industrial pollutants in waterways such as mercury, nitrogen or phosphorous. In this case, heat is the pollutant that causes stress in salmon, which are protected as an endangered species, and prevents them from spawning.

Oregon and Washington have set a maximum temperature of 68 degrees Fahrenheit in the rivers to protect fish. According to the EPA, water temperatures at the dams regularly exceed that threshold between July and October.

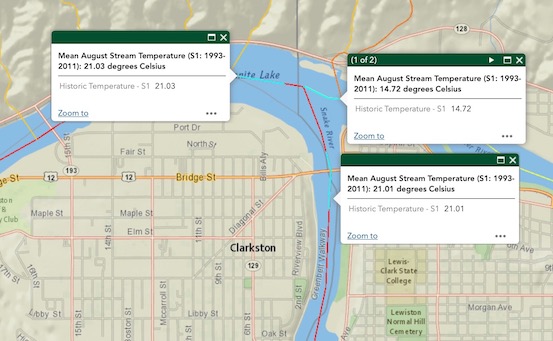

Conditions vary by time and location, but are generally warmest farther downstream in August, ranging from 70 degrees at McNary Dam to nearly 72 degrees at Bonneville Dam on the Columbia River. Temperatures also exceeded 68 degrees in the lower Snake River, from 69 degrees at Lower Granite Dam to 71 degrees at Ice Harbor Dam.

Environmentalists argue just a few degrees can be the difference between life and death for fish.

In summer 2015, warm water exceeding 70 degrees was blamed for the death of 250,000 Snake River adult sockeye salmon, about half of that year's anticipated run. Groups have urged the federal government to consider removing the lower Snake River dams to avoid a repeat catastrophe.

Brett VandenHeuvel, executive director of Columbia Riverkeeper, said the EPA's TMDL is a victory for salmon and steelhead in the rivers.

"It's been known for a long time that the rivers are too hot and getting hotter every year," VandenHeuvel said. "This EPA report is the first time where heat pollution is assigned to individual dams, and there will be a requirement for the dam operators to address that pollution and cool the rivers."

Columbia Riverkeeper, Snake River Waterkeeper, Idaho Rivers United, the Institute for Fisheries Resources and Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen's Associations successfully sued the EPA in 2017 to write the TMDL. The EPA initially wrote a draft report in 2003, though it was never finalized.

The report is now out for public comment until July 21. And while it does not dictate specific actions to cool the rivers, states are now considering plans to implement the temperature standard.

Melissa Gildersleeve, watersheds section manager for the Washington Department of Ecology, said the agency is reviewing the TMDL and seeing what it means for issuing future water quality permits. That includes permits to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which operates the federal dams for flood control, hydroelectricity and barge traffic shipping agricultural goods around the Northwest.

"There are a variety of different tools we could be looking at," Gildersleeve said. "All those dams are distinctly different."

Gildersleeve said they will work together with the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality on plans for a stretch of the Columbia River that forms the border between the two states.

"We actually have a history of working together on the Columbia River," she said.

Matt Rabe, a spokesman for the Army Corps Northwest Division based in Portland, said the focus remains on passage and survival of salmon at the dams while continuing to operate them for their congressionally mandated purposes.

Rabe said the lower Snake River has historically been warmer during the summer months, even before the dams were built. He mentioned releasing water from Dworshak Reservoir, on the North Fork Clearwater River in Idaho, as one example of what the agency is doing to cool water along the lower Snake River.

Environmental groups, however, remain adamant that breaching the dams is the best way to save salmon.

"Snake River dam removal not only solves the problem of hot water, it has the additional benefit of allowing fish to reach high-quality spawning habitat," VandenHeuvel said.

Kurt Miller, executive director of Northwest RiverPartners, a group that represents nonprofit electric utilities in Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana and Wyoming, emphasized the value of low-cost hydroelectricity produced by the dams. He worries the temperature standard for salmon is not realistically achievable, and places an unfair burden on dam operators.

Chiefly, Miller said the TMDL shows water coming into the two river systems from Canada and Idaho already exceeds Oregon and Washington standards by over 5.4 degrees Fahrenheit in August. Even the EPA report noted that the current water quality standards in Oregon and Washington "present a significant challenge."

"You can see that the issue has a lot to do with air temperature, more than it does with the dams," Miller said.

Water temperature is a legitimate concern, but depending on what the states do it could reduce the availability of hydroelectricity and increase electricity bills for millions of customers, Miller said.

"If you set up standards that are not possible to attain, what are the ramifications of that?" he said. "That's concerning to us. It seems like you're setting up the dams to fail."

Related Pages:

Comment on EPA's "Cold Water Refuge" Plan by bluefish.org, 12/5/19

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum