forum

library

tutorial

contact

Idaho Power is Waging War on

Renewable Energy. Is it Winning?

by Stephen Ernst

High Country News, September 2, 2013

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Idaho Power is Waging War on

by Stephen Ernst

|

One of the West's great old-school monopolies and its multi-pronged attack on wind and solar.

BOISE, IDAHO -- When Brian Jackson's cellphone rang Dec. 13, 2010, something he'd chased for three years seemed within reach. The wiry engineer had invested his life savings in Rainbow Ranch, a pair of wind farms that average 10 megawatts, each capable of powering some 8,400 homes a year. He hoped to build them in southern Idaho, between Pocatello and Twin Falls.

BOISE, IDAHO -- When Brian Jackson's cellphone rang Dec. 13, 2010, something he'd chased for three years seemed within reach. The wiry engineer had invested his life savings in Rainbow Ranch, a pair of wind farms that average 10 megawatts, each capable of powering some 8,400 homes a year. He hoped to build them in southern Idaho, between Pocatello and Twin Falls.

"My goal was to help people stay on the land," says Jackson, 46, whose family has farmed in Idaho for a century. He expected to pay off the debts of the approximately $70 million project in about 15 years, then earn several million a year, half of which would go to the landowner. "Wind is a huge asset to a farmer. They can make a little money and keep working the land."

All Jackson needed was a contract with Idaho Power, the state's largest utility. So he was delighted when the company's contracts coordinator called: Could Jackson pick up the contract, or should he mail it?

Jackson raced to downtown Boise. With one kid in college and four younger ones, he had a lot to lose. But a little-known federal law minimized the risk. The Public Utilities Regulatory Policy Act, or PURPA, passed on the heels of the 1970s energy crisis, requires utilities to purchase power from small alternative projects like Rainbow Ranch. It seemed Jackson's gamble was about to pay off.

He gave the contract one last read and handed it back before the day was out. "It was almost like Christmas Day," he recalls, trailing off into a rare silence: "We were so close. . . ."

What Jackson didn't know that day was that Idaho Power was closing its doors to wind and solar. Idaho is the toughest place in the West for renewable energy. Other states, aside from Utah and Wyoming, have adopted renewable portfolio standards to lower climate-changing emissions. Those policies require utilities to include a certain percentage of renewable energy in their power mix. Accompanied by federal tax breaks, they've created a market for wind and solar. But Idaho's overwhelming Republican majority is apathetic about climate change and wary of raising electricity rates. A renewable portfolio standard died several years ago while only in a legislative committee.

PURPA promised wind developers a market. But in 2010, at the request of Idaho Power and two other major utilities, the Idaho Public Utilities Commission lowered the 10-average-megawatt size limit for PURPA contracts enough that no commercial project would qualify, effectively blocking the only path for wind and solar. The change would take effect Dec. 14, a deadline Jackson thought he'd beaten. But Idaho Power waited three days to sign and submit the contract to the state utility commission. By then, contracts were only guaranteed for projects under 100-kilowatts -- roughly enough energy to power a single home.

That sank Rainbow Ranch and 14 other wind farms. Jackson lost his investment and money from friends and family -- $500,000 altogether. Last July, before he landed a job with a mining company, his phone and utilities were cut off. "I just never saw a scenario where (Idaho Power would) stonewall us to the very end," he confesses.

Today, Jackson is among a small band of clean energy advocates attempting to force the utility to embrace renewables. In March, they acquired a powerful ally: For the first time, the federal government sued a state for failing to enforce PURPA. But changing Idaho Power won't be easy.

"The (renewable) investment atmosphere in Idaho is the worst in the Western U.S.," says Peter Richardson, a Boise attorney who represents wind developers and Idaho Power's industrial customers. "It's almost hostile."

Utilities tend to be stodgy, conservative beasts. Left to themselves, they're unlikely to abandon the hulking coal-fired power plants that generate about 40 percent of Americans' electricity, because they provide cheap and abundant power and utilities are guaranteed to profit from its sale. So-called "investor-owned utilities" like Idaho Power are publicly sanctioned monopolies granted exclusive access to a city or region's customers so long as they provide affordable, reliable power. They profit by building new power plants and transmission lines, billing customers for construction and raising rates enough to reap a "reasonable rate of return." Public commissions oversee utilities, but once they have approved a new power plant and attendant rate hikes, utilities have little incentive to forsake it and its profits.

But what serves utilities' bottom line doesn't always serve the public's energy goals. That was true when PURPA was passed in 1978 to address soaring electricity prices by promoting clean energy and diversifying the country's energy mix. And it's true now, with the impacts of carbon a growing concern.

Political pressure can make utilities change, but seldom without a fight. In the early to mid-2000s, consumers and legislators began demanding that utilities lower emissions by generating clean electricity. Colorado's biggest utility, Xcel Energy, and small rural power providers successfully lobbied against renewable energy standards at the state Legislature. In 2004, Xcel bankrolled the campaign against an RPS ballot measure, saying renewable energy was too expensive and unreliable; voters disagreed, approving the renewable standard by a 7-point margin. PNM, New Mexico's major utility, also fought the state's initial renewable mandate. In the most liberal Western states, utilities didn't oppose the mandates outright. Still, they had reservations. As the amount of wind energy grew, Pacific Northwest utilities worried that a sudden drop -- or escalation -- in power would make the grid collapse.

Those fears were soon put to the test. Renewable portfolio standards -- plus carbon emissions limits for new plants in Oregon and Washington -- were historic shifts: For the first time, utilities had to consider climate change when building new power plants. No longer could they just exploit coal, the cheapest resource. Suddenly, gusty hilltops around the Northwest's Columbia Gorge were sprouting hundreds of turbines. Wind power did challenge grid operators, who must ensure that the amount of electricity being fed to power lines is equal to the amount being consumed. Coal, natural gas, nuclear and hydroelectric power plants make this task relatively simple by putting out consistent streams of energy. Wind does the opposite; its gusts can fluctuate wildly within 15-minute windows. Grid managers could no longer just tweak the output of individual plants to match demand. A certain amount of energy would have to be kept in reserve to be used in a pinch to prevent blackouts. Stabilizing wind also increased operating costs because some generators were kept on, just in case, even if power wasn't sold. Still, renewable energy standards offered opportunity. Big utilities acquired or built wind farms and secured rate hikes to cover the cost.

What resulted was widespread development of the Northwest's second great renewable resource. Thanks to large hydroelectric dams, which generate about 60 percent of the region's power and have predictable fluctuations, grid operators eventually married wind to water. In 2000, Washington, Oregon, Idaho and Montana hosted about 50 megawatts of wind-power capacity. Today, that figure is 8,500 megawatts, and the Northwest boasts one of the country's faintest carbon footprints.

(bluefish notes: It is interesting to compare this to the 1050 aMW (~3000 MW peaking) produced by the four Lower Snake River dams. In 2000, many in the region said that these four dams could never be replaced wind wind and solar. It seems as though this prognostication was incorrect.)Not once have the lights blinked out because the breeze faltered. Monthly electric bills are higher, but wind is only one reason; over the past six years, utilities have also invested heavily in updating infrastructure. And they still enjoy comfortable profit margins. In other words, fears of a collapsed grid and exorbitant costs proved unmerited. None of this, however, seems to matter to the wind debate in Idaho.

There's an old joke that Idaho is the only state named after a utility -- a nod to Idaho Power's reputation as a major powerbroker. The nearly 100-year-old company secured its station in the 1950s, when, after a struggle over whether Snake River hydropower should be developed by public or private interests, it got permission to build its three-dam Hells Canyon Complex. The complex generated more power than Idahoans used, so excess electricity was sold out of state, and Idaho Power promoted new farmland development at home -- irrigated with electric pumps. Today, the company provides over three-quarters of Idaho's power, and its 17 dams provide some of the nation's cheapest electricity.

Idaho Power has frequently fought to protect its water rights and keep reservoirs full. Its lawyers and lobbyists have allied with industrial pulp mills and irrigators with superior water rights to curtail newer water users, worked with lawmakers to broker compromises, and occasionally played hardball. In 1994, the company successfully lobbied the Legislature to affirm that the utility's hydropower water rights had priority over farmers wanting to replenish aquifers. Later, it tried to use that law to sue the state to stop diversions from the Snake River destined for aquifers. It also supports politicians and political organizations, primarily conservative ones. Last year, it gave its first-ever donation to the Idaho Freedom Foundation, the state chapter of the Tea Party, which generally opposes renewable energy mandates. And since 2004, Idaho Power has contributed $660,535 to federal and state campaigns, according to the National Institute for Money in State Politics.

That doesn't mean it always gets what it wants. PURPA, in particular, has been a persistent thorn in its side. Before wind developers appeared, irrigators fought the company and won, forcing it to buy power from small irrigation-company dams, which offset farmers' electricity costs.

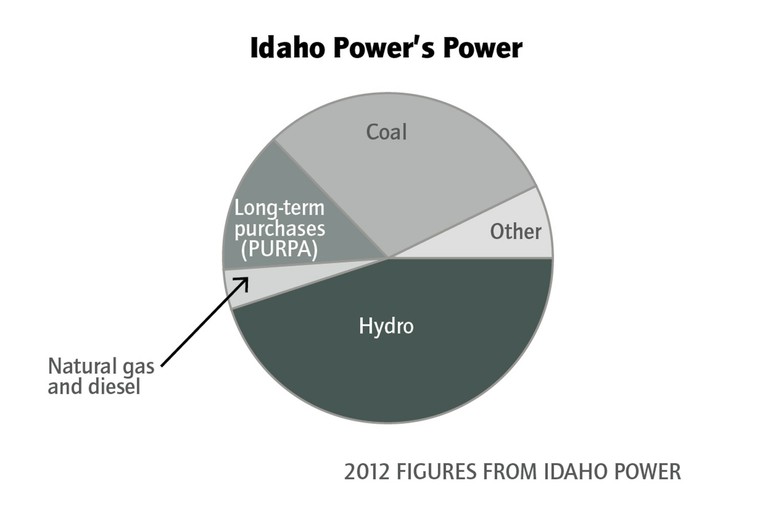

But renewable energy developers lack the political clout of farmers, and their act in this drama has played out differently. Between 2006 and 2010, Idaho Power took on 577 megawatts of wind power because PURPA obligated it to; wind now represents about 8 percent of its power capacity. When Jackson signed the Rainbow Ranch contract, Idaho Power anticipated adding 300 megawatts more.

These deals were a boon to wind developers, but not to Idaho Power. The rate utilities have to pay for power under PURPA is based on "avoided cost" -- what it would cost Idaho Power to generate the same amount by building its own natural gas plant. The utility passes those costs onto customers, but doesn't profit. Sometimes, it loses money. If wind turbines kick out juice in the middle of the night, when there's no demand for power, Idaho Power tries to sell it on the open market. But if prices are lower than the rate set under PURPA, it does so at a loss, which is eventually passed onto ratepayers.

As PURPA contracts piled up, Idaho Power complained that wind developers were abusing the law by carving large projects into 10-average megawatt slices so they'd qualify. But mostly it argued that wind was too expensive. "The costs to our customers are staggering," says Dan Minor, Idaho Power's chief operating officer. "We felt we needed to call a timeout on PURPA."

Wind has raised electric bills in Idaho, but whether the increase has been staggering is a matter of perspective. Last year, Idaho Power paid $67.9 million for PURPA-contracted wind. Its residential customers pay an average of $93 a month for electricity. About $7.20 of that covers the added expense of wind.

Still, in 2010, at the request of Idaho Power and the state's other major utilities, PacifiCorp and Avista, the Idaho Public Utilities Commission limited guaranteed PURPA contracts for solar and wind to projects under 100 kilowatts. (The change doesn't apply to other renewable energy, like the methane digesters used on dairy farms to convert manure into power.) Wind development skidded to a halt.

It was Idaho Power's opening salvo in a war on wind -- and, to a lesser extent, solar. Recently, the company supported a narrowly defeated bill that would have put a two-year moratorium on wind development. Earlier, in 2011, the utilities successfully lobbied the Legislature not to renew the sales tax exemption on energy equipment -- a key financing tool for wind developers. And that April, in a direct-mail campaign and ads on conservative websites like The Drudge Report and Fox News, Idaho Power called wind expensive, unnecessary and unreliable. In most other states, this kind of public bashing of clean energy would have drawn the ire of the governor and legislature. Here, it didn't.

The three-member Public Utilities Commission -- which doesn't make policy, but interprets state law -- has occasionally pushed back. During periods of strong wind and low energy demand, Idaho Power would shut off wind farms, claiming it was cheaper to run only its coal and natural gas plants. The PUC and the feds stopped that earlier this year. And this July, the PUC struck down Idaho Power's request to limit the amount of residential solar generation on its system.

Idaho Power says it's not ideologically opposed to renewable energy: "We don't think wind is the right resource for our customers today," Darrel Anderson, the company's president and chief financial officer, says. Anderson says Idaho Power's position reflects its customers' beliefs, noting low participation in the company's green-power programs and outside polls indicating that Idahoans are skeptical about climate change and unwilling to pay extra for renewable energy.

"We have an obligation to our customers to provide reliable and low-cost power. Wind does not fit those characteristics," Anderson says. "It's really a minority in the state that have taken exception to what we've done."

Kiki Tidwell is one of that minority's most vocal members. On a sunny day last September, the petite, well-coiffed blonde sat in her Seattle condo happily discussing clean energy, producing stacks of research and hand-written notes. "I see a lot of similarities between clean energy technologies today and the early days of the personal computer," Tidwell said. "We are in the early stages of a massive market with global ramifications."

Tidwell, who grew up in Hawaii, worked for a time in her family's Outrigger Hotel and Resorts, a global chain of posh beachfront getaways. She came to Idaho 30 years ago because it had the "best damn ski mountain anywhere," and built a successful career in real estate. Now, she splits her time between Hailey and Seattle, where she's an active member of the Northwest Energy Angels, a group of wealthy investors who fund clean energy start-ups. When Jackson lost his Rainbow Ranch investment, Tidwell lent him money to keep his kid in school.

Tidwell doesn't call herself an environmentalist. She prefers "capitalist," and is an ardent free-market Republican. But she sees renewable energy as a tool for rural development. Idaho could generate 18,074 megawatts of energy from wind, but has only 972 megawatts of installed capacity. Tidwell believes that developing more wind and solar, while increasing energy conservation through a fleet of recently installed smart meters, could give Idaho counties tax revenues while saving consumers money.

And coal, she believes, is too risky an investment. That's why in 2009, Tidwell, who owns a chunk of Idaho Power stock, masterminded a shareholders' resolution urging the utility to shrink its carbon emissions -- another way of telling it to kick its dependence on coal, which generates about 42 percent of its power. The company objected, unwilling to ditch coal or bring new wind or solar online until the scope of federal climate legislation was clear. The shareholders' resolution was financed by Tidwell and filed by the shareholder advocacy group As You Sow, along with Calvert Asset Management and Trillium Asset Management, which own stock or represent shareholders. "Companies all across the country are planning to reduce carbon emissions and to capitalize on renewable energy opportunities," Lily Donge, senior analyst at Calvert, said at the time. "Idaho Power's wait-and-see strategy raises a lot of red flags for investors."

For years, environmental activists have unsuccessfully tried to change utilities through shareholder resolutions. But this time, in Idaho, they triumphed, with 52 percent of the vote. "The company takes this vote seriously and will consider adopting quantitative goals this year," Idaho Power CEO LaMont Keen responded. The Idaho Statesman opined that the resolution was "a favor disguised as a mandate," adding, "The issue comes down to timing. Does Idaho Power do the right thing now, or does it wait until later?"

The company responded by setting a goal of lowering carbon emissions 10 to 15 percent below 2005 levels. It's surpassed that goal: Last year, carbon emissions were 27 percent below 2005 levels. But critics say that's because of a historic, recession-induced drop in electricity demand, which allowed Idaho Power to rely on hydro and natural gas-fired power plants and rarely use its smallest plant. There's no guarantee this pattern will hold as demand rises again.

Idaho Power gets most of its coal power from two out-of-state plants: Nevada's 538-megawatt North Valmy Generating Station and Wyoming's 2,110-megawatt Jim Bridger Plant. Both need pollution controls to address mercury emissions and haze, and within the next five years, new nitrogen oxide controls, too. And then, of course, there's carbon dioxide. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has yet to draft CO2 limits for existing plants, but President Obama directed it to do so this summer. Additionally, Jim Bridger stores the wastewater and sludge from burning coal in open, unlined ponds. EPA is considering stiffer regulations for those ponds, even labeling them "toxic." Should that happen, Idaho Power and the plant's co-owners would have to treat nearly 50 years of slurry as hazardous waste, and the cost could shut the plant down.

Earlier this year, Idaho Power released a long-awaited study of the costs of upgrading its coal plants versus converting to natural gas or building new gas-fired plants. It put the price of the cheapest option -- haze and mercury controls at Jim Bridger -- at $140 million, and asked the PUC to bill customers for the upgrades. In contrast, faced with similar choices, Portland General Electric simply decided to close its Boardman coal facility -- which Idaho Power owns 10 percent of -- and build a natural gas plant. NV Energy, Idaho Power's partner in the Valmy plant, is also planning to close several coal facilities, mostly in southern Nevada, but is keeping Valmy for now.

Environmentalists contend Idaho Power low-balled the costs with a piecemeal upgrade strategy that addresses specific pollutants in the short term instead of accounting for the total cost of complying with future regulations. "They know that around 2018 they are going to have to comply with new regulations for nitrogen oxide emissions," notes Ben Otto of the Idaho Conservation League, "but in this study they give it zero compliance cost."

Meanwhile, the utility marginalized some of its most vocal critics. For years, the Snake River Alliance has pushed the utility to beef up its conservation and energy-efficiency programs. In May 2012, when Idaho Power held its annual shareholders meeting in a blocky downtown Boise office tower, the group organized its own "careholders" meeting across the street. Some 40 people rallied under a hand-painted sign proclaiming, "Idaho Power: We care, choose efficiency." The star of the show was "Mr. Idaho Power," who arrogantly dismissed questions about emissions and climate change, drawing chuckles and boos.

It was a small protest, and Idaho Power could have ignored it. But executives thought Mr. Idaho Power vilified Board Chairman and CEO LaMont Keen. The next week, the utility booted the Snake River Alliance from its resource planning committee -- which helps the company chart how it will meet future energy demand -- criticizing the group's "wind at all costs" attitude. Ken Miller, the Snake River Alliance's clean energy director, retorts, "We've never advocated for replacing a coal plant with wind. That's just impossible."

Mark Stokes, the utility's power supply planning manager, says the Alliance was expelled because "they called our CEO a liar," adding that Miller still attended public resource committee meetings, giving valued input. "They probably do feel we bullied them to some degree. But the campaign we started was really designed to educate our customers around wind issues. If that's what they consider hardball, well, it is what it is."

This hostility toward renewable energy is ironic, say critics, because the utility is perfectly positioned to kick coal. Its anti-wind battle has played out in the shadow of Langley Gulch, a controversial new natural gas plant that came online last summer, raised electricity rates by about 6.5 percent, and was justified partly as being necessary to integrate wind. With two more gas plants and its Snake River dams, says Boise attorney Richardson, Idaho Power's portfolio is primed for more renewables. "Gas and hydro are what utilities need to balance wind, and they have plenty of both."

But the addition of Langley Gulch's 330 megawatts means there's almost always excess power. Given this surplus, Idaho Power has sought to ditch renewables and backpedal on conservation. Energy efficiency is strongly supported by business leaders and elected officials, and historically Idaho Power has boasted some of the West's strongest efforts. But last year, it suspended programs that click off air conditioners and irrigation pumps during peak demand.

When the utility sought approval to build Langley Gulch, Richardson -- along with a coalition representing all of Idaho Power's various customer groups -- argued it wasn't needed because demand was way down. It would have been cheaper to beef up renewables while managing demand and investing in efficiency to shave summer spikes. At the very least, says Richardson, the company should have had to close its Valmy plant to build Langley Gulch.

Now, hope for a cleaner future may rest on a new transmission line. The company recently released its integrated resource plan, a 20-year road map for meeting future demand, which is expected to eventually increase above what even Langley Gulch can satisfy. The plan favors building a transmission line from Boardman, Ore., to Melba, Idaho, that would access wind, hydro and natural gas power in Washington and Oregon. Additionally, starting in 2016, Idaho Power plans to have conservation programs in place to reduce electricity use by 150 megawatts during periods of high demand.

Clean energy advocates aren't celebrating yet, but they're encouraged by the proposed transmission line, which could give the company new options for replacing its coal power and generate revenue. Access to cleaner energy, and the likelihood that carbon will eventually be regulated, could make it increasingly hard for the company to justify Valmy. "It's not like, 'Hallelujah! They got religion!' " the Snake River Alliance's Ken Miller says of the company's 20-year plan. "But it's a cleaner option."

And in March, the federal government raised hopes that Idaho's new PURPA rules may be overturned, claiming that Idaho overstepped its authority when it changed the rules. If it wins, Jackson could build Rainbow Ranch.

The Snake River Alliance didn't protest at this May's annual meeting. But about a dozen pro-clean energy stockholders showed up to pepper CEO Keen with questions about emissions and renewable energy. After one particularly testy exchange, a frustrated Keen told the crowd that the shareholders meeting wasn't the forum to discuss climate change or new energy technologies; it was a time to talk profits. The news on that front was good: Last year, the net income of IdaCorp, Idaho Power's parent company, rose to $168 million, the fifth straight year of positive earnings growth. Idaho Power is doggedly focused on the bottom line, and it delivers. Keen emphasized that in his response to the climate-concerned shareholder, underscoring the wide gulf that remains between Idaho Power and renewable energy activists: "This should be a celebration for IdaCorp," Keen complained. "We had a great year."

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum