forum

library

tutorial

contact

Endangered Southern Resident Orca Whales

are Last in Line for Salmon. Here's Why

by Kimberly Cauvel

Skagit Valley Herald, December 27, 2019

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Endangered Southern Resident Orca Whales

by Kimberly Cauvel

|

Two studies and a state report released this month build on the efforts to understand what's impacting the region's endangered Southern Resident orca whales and what steps could be taken to help save them.

Two studies and a state report released this month build on the efforts to understand what's impacting the region's endangered Southern Resident orca whales and what steps could be taken to help save them.

Researchers and wildlife managers have for years suggested that the Southern Resident orcas, which spend several months of the year in the Salish Sea and coastal waters of Washington, are struggling to find large, nutrient-rich chinook salmon to eat.

Studies recently published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggest the Southern Resident orcas are competing with other fish-eating orca populations of the North Pacific Ocean and that orca calves born to families without grandmothers have a lesser chance of finding chinook to eat and surviving to adulthood.

Meanwhile, a draft state report released Dec. 20 concludes it's not clear whether a move long called for by environment and wildlife groups -- to remove dams on the lower Snake River -- would significantly boost the number of fish available to the region's orcas.

Removing four dams on the lower Snake River in Southeast Washington, where it curves from the Idaho border toward the Oregon border, could improve conditions in the river system for salmon, according to the report.

But it's less clear how quickly and by how much the chinook salmon in that river system would increase, and whether it would be enough to help the orcas stave off extinction, according to the report.

That document, Lower Snake River Dams Stakeholder Engagement Report, is available for public comment until Jan. 24.

"I encourage Washingtonians to get engaged in the public comment period over the next month and share their input on what should be done," Gov. Jay Inslee said in a news release Dec. 20. "We need to hear from a variety of people from different regions and perspectives."

While agricultural and energy interests in the southeast portion of the state have a stake in the discussion, Western Washington communities are invested, too, in the quest to find ways to generate more salmon that could feed a dwindling Southern Resident orca population that is down to 73 whales.

CULTURAL, ECONOMIC IMPACT

The state study was initiated out of concern for the orca whales, and based on a recommendation from Inslee's Southern Resident Orca Task Force that convened in 2018. The goal is to understand how much the orcas, which are culturally and economically significant to the Salish Sea region, might benefit from such a large undertaking -- and at what cost.

The published studies that came out ahead of that state report point to other challenges the orcas face in finding fish to eat.

A University of Washington study published Dec. 16 suggests the Southern Residents are losing fish to growing resident orca populations that spend most of their time in waters along British Columbia and Alaska.

Those northern populations are larger in number, according to the study, with about 300 whales in the Northern Resident population along B.C. and about 2,300 in the population found in Alaska.

Because chinook salmon born in Washington rivers migrate to areas of the Pacific including off the shores of Alaska, the northern orcas are first in line for the fish, with the endangered Southern Residents last in line.

"This study highlights the fact that local management strategies need to be put in a much broader spatial context," lead study author Jan Ohlberger, of the university's School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences, said in a news release. "In this case, that means the whole coast, because that's where the fish migrate."

GRANDMOTHERS' HUNTING SKILLS

Ohlberger and four co-authors analyzed 40 years of data on wild chinook populations, hatchery chinook, fishing pressure and ocean conditions. They found the three-fold increase in neighboring fish-eating orca populations could be an important factor in how many fish are available to the Southern Resident orcas.

Another factor that can hinder Southern Residents' ability to find fish is whether a grandmother is alive to pass down hunting knowledge and help care for calves, according to a University of York study published Dec. 9.

That study found that grandmother orcas no longer producing their own young play a vital role in helping calves survive.

The researchers studied 36 years of data on calves born to family groups in the Southern Resident orcas of Washington and the Northern Resident orcas of British Columbia.

They found that calves with grandmothers past menopause may have a 4.5 times higher chance of survival than calves whose grandmothers died in the previous two years, according to the study.

Related Sites:

Fisheries Canada: www.pac.dfo-mpo.gc.ca

National Marine Fisheries Service: www.nwr.noaa.gov

Orca Network: www.orcanetwork.org

bluefish corresponds with lead researcher Jan Ohlberger

Hi Scott

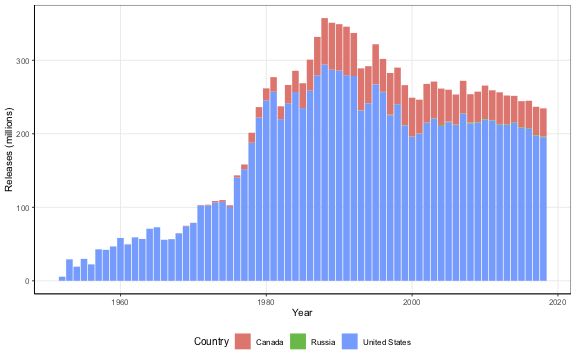

I appreciate your interest and comments. Regarding hatchery releases of salmon: it is correct that hatchery production of Pacific salmon has remained relatively stable since the 1980s, as shown on your figure, and also that production of hatchery Chinook salmon has declined over that time period, as mentioned in our paper. Chinook salmon hatchery production is only a small fraction of the total salmon release, which is dominated by chum and pinks. Here is a similar plot to yours using North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission data for Chinook salmon only:

Other Pacific salmon may also affect the growth and maturation of Chinook salmon, such that the total number of hatchery salmon in the North Pacific Ocean might be important, as discussed briefly in our paper.

Regarding your comment on CR June Hogs: I totally agree that expanding our data further back in time would be instructive, as would considering the contributions of local extirpations. The disappearance of local populations, especially if more likely for those that reached particularly large sizes, could be a contributing factor that we did not account for in our analysis, primarily due to lack of data. We also acknowledge that there are likely some regional differences in terms of factors that contribute to local trends. I think we have only scratched the surface...

Thanks for sharing your thoughts and happy new year!

Jan

While reading your recent research Resurgence of an apex marine predator and the decline of prey body size, I am left with a question about the influence of hatchery fish. If I understand your paper correctly, your group appears to have discounted their contribution to lower body size of salmon.

I sincerely do find it is interesting that your discussion of wild Alaskan Chinook have decreased in size, and this has supported the discounting of hatchery effects.

"Chinook salmon in western Alaska, have experienced similar declines in the size at age of older fish."Primarily this email is in regards to the suggestion that hatchery production has decreased over the past two decades. The North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission data does not appear to comply with this contention."Furthermore, coast-wide hatchery releases of Chinook salmon increased rapidly in the 1970s and 1980s but have declined steadily since the late 1980s."It is interesting to me that your model finds when predators are eating more than 1/3 of the available population, then this size reduction becomes forceful. It would then follow that it is the shortage of prey in comparison to the predator numbers that is a principal driving force of size selection. This fits well with numerous predator prey studies showing that it is best to restore prey populations prior to restoring predator populations.One other thing to note is that the once-famous "June Hogs" of the Columbia basin have been extirpated by the construction of the extensive hydrosystem in their spawning and rearing region. Expanding your data set to an older time frame would be instructive.

I look forward to your eventual response to my questions, but I fully appreciate this being the holiday season and I am in no hurry to hear from you.

Happy Holidays,

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum