forum

library

tutorial

contact

What Happens If You Add Lots of

Wind and Solar Power to the Grid?

Brad PlumerWashington Post, September 25, 2013

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

What Happens If You Add Lots of

Brad Plumer |

Wind power is no longer an insignificant energy source in the United States. Turbines across the country provided 4 percent of the nation's electricity last year -- enough to power half of Mexico.

Wind power is no longer an insignificant energy source in the United States. Turbines across the country provided 4 percent of the nation's electricity last year -- enough to power half of Mexico.

But as wind power (and its cousin, solar power) keeps expanding, it could pose some hassles and headaches for those in charge of the nation's electricity grid.

What would happen if we tried to get, say, one-third of our electricity from wind and solar? How much would that cost? Would we need to build a ton of new transmission lines to remote areas? And what would we do for back-up electricity when the wind's not blowing or the sun's not shining?

Those are surprisingly tricky questions to answer. So it's worth checking out a fascinating series of studies the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) has been conducting over the past few years, examining in excruciating detail what would happen if the western half of the United States tried to get up to 35 percent of its electricity from wind and solar.

The main upshots: It likely wouldn't be cheap up front. But the existing electric grid could probably handle a big infusion of renewable energy without huge infrastructure changes. And, contrary to some recent arguments, putting that much wind and solar on the grid really would cut pollution by a large amount -- and curtail the greenhouse gases that are warming the planet.

Getting to 35 percent wind and solar

Back in 2010, NREL published the initial phase of its study, looking at what would happen to the Western Interconnection (see map on original page) if the region got up to 35 percent of its electricity from wind and solar -- specifically, 30 percent from wind and 5 percent from solar.

First, the bad news: This probably wouldn't be cheap up front. After all, you'd have to build a bunch of new wind and solar farms, and those are still more costly than building, say, a new natural gas power plant (although prices for wind have fallen sharply in recent years, and this doesn't include the social cost of pollution -- adding that gives clean energy more of an edge).

The somewhat better news: The western region wouldn't have to build massive new transmission lines to accommodate these power plants, as previously thought: "The integration of 35% wind and solar energy into the electric power system," NREL found, "will not require extensive infrastructure if changes are made to operational practices."

Grid operators would need to find ways to juggle supply and demand to accommodate intermittent sources. But, the NREL study found, this is largely doable with existing technology -- from improved forecasts for the sun and wind to "demand response" programs for large consumers of electricity. And that's particular true if the wind and solar farms are spread out across a wide geographic area.

The environmental impacts, meanwhile, would be significant. The initial NREL study estimated that increasing wind and solar's share of electricity to 35 percent would cut sharply into natural gas and coal's share. It would also cut carbon-dioxide emissions from the grid by as much as 45 percent. At least, in theory ...

Juggling the grid

In recent years, however, experts have raised other concerns about adding so much wind and solar to the power system. Grid operators would need to ask natural gas and coal plants to fire up periodically to fill in the gaps when the sun goes down or the wind dies. That's costly, and it's potentially a dirty process. Some critics have even argued that adding too much wind might, paradoxically, boost greenhouse-gas emissions.

That sounds bad. Yet the newest NREL study, released this week, says that those fears are misplaced. Wind and solar power really do reduce emissions significantly.

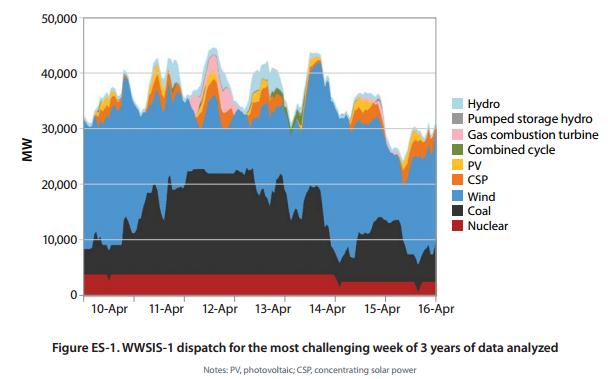

After modeling a year's worth of electricity use (see right for an example), the NREL study found that if you add a lot of wind and solar to the grid, there will be some "cycling" of natural gas and coal plants to balance the load. That does lead to more wear and tear on power plants and increases operating costs by up to $157 million. But that's a small amount compared to the fuel savings of around $7 billion by switching to wind and solar.

After modeling a year's worth of electricity use (see right for an example), the NREL study found that if you add a lot of wind and solar to the grid, there will be some "cycling" of natural gas and coal plants to balance the load. That does lead to more wear and tear on power plants and increases operating costs by up to $157 million. But that's a small amount compared to the fuel savings of around $7 billion by switching to wind and solar.

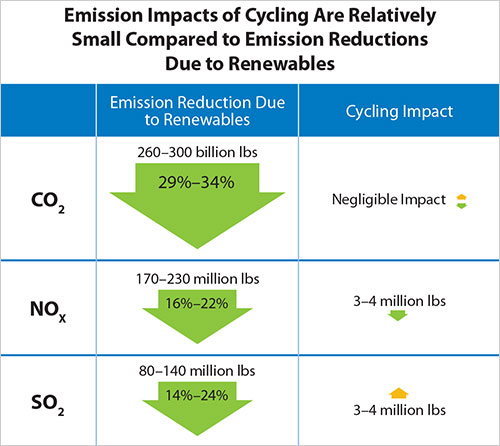

The same goes for pollution. "The negative impact of cycling on overall plant emissions is relatively small," the study concluded. "The increase in plant emissions from cycling to accommodate variable renewables are more than offset by the overall reduction in [other pollutants, such as carbon-dioxide and sulfur-dioxide]. In the high wind and solar scenario, net carbon emissions were reduced by one third." Here's a graphic (at top of article):

As a result, the NREL team's results "disagree with some previous studies" on this score and find "that wind does not increase overall emissions and that avoided emissions from wind and solar have not been significantly overstated."

But is any of this realistic?

Now, a word of caution here. The NREL team only modeled the operations of the Western Interconnection with a much bigger share of renewable power.

But these precise results, the report cautions, are grid-specific. Other parts of the United States -- or other countries -- might have different challenges in scaling up renewables.

Another place to look is Germany, which has used subsidies to ramp up wind and solar power dramatically in recent years -- both sources provided some 15.7 percent of the nation's electricity this past August. That transition hasn't been without hiccups, however.

A long investigation in Der Spiegel rattled off some of the problems with Germany's big renewable push. Thanks to generous government subsidies to solar and wind producers, which are borne by all households, electricity bills have doubled since 2000. And the nation's plans to integrate offshore wind into the grid will require some $27 billion in transmission lines. What's more, Germany has had to ramp up its old coal plants significantly to balance the load -- particularly now that the country is shutting down its nuclear plants.

The NREL study suggests that, at least in theory, the western United States could avoid many of these problems. But it's hard to know how a dramatic ramp up of wind and solar would actually work in practice -- and whether there might be other surprises along the way.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum