forum

library

tutorial

contact

Salmon Can Once Again Explore

Marsh Mapped by Lewis and Clark

by Rob ManningOregon Public Broadcasting, February 25, 2011

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Salmon Can Once Again Explore

by Rob Manning |

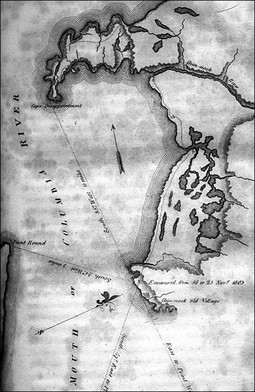

Historians say Lewis and Clark's Corps of Discovery mapped -- but probably didn't bother to explore -- a marsh just north of the mouth of the Columbia River.

Historians say Lewis and Clark's Corps of Discovery mapped -- but probably didn't bother to explore -- a marsh just north of the mouth of the Columbia River.

In recent years, federal officials have become convinced those wetlands are worth exploring -- and worth restoring -- to save salmon.

But as Rob Manning reports, the hurry to get projects going has gotten federal officials into hot water with a key scientific panel.

205 years ago, William Clark mapped a marsh on the north side of where the Columbia River opens wide and empties into the Pacific.

Scientists believe that historically, juvenile salmon used the area to feed before heading out to sea.

But more recently, a railroad line and then Highway 101 cut the wetlands off from the river.

It was still impassable when Amy Ammer with the Columbia River Estuary Study Taskforce toured the area, two years ago.

Amy Ammer: "So, none of the juveniles that are in the Columbia River can make it through to here."

Rob Manning: "This is basically unusable wetland then, as far as the fish are concerned."

Amy Ammer: "As far as the fish are concerned, it's unusable and a deathtrap."

It was a deathtrap for the few salmon that actually got in. But mostly salmon couldn't get in. And that meant they missed out on food, according to a salmon recovery consultant along on the tour, Allan Whiting.

Allan Whiting: "The data is suggestive enough now, to say that salmon using these restored marshes - their stomachs are full, they've gotten the food from the marshes that have been restored. And they're healthier as a result. And that's just based on these first initial projects. You know, we need a lot more of these sites to prove that over time."

Whiting hasn't been alone in calling for more projects in the estuary. So has Judge James Redden - the judge who's been in the middle of years of litigation over the Columbia River.

Largely because of Redden's statements, the Bonneville Power Administration has committed millions to estuary projects in the last few years.

One of their signature efforts has been to take out that "deathtrap" near present-day Fort Columbia.

After years of planning and fundraising, construction crews pulled out the last of the barriers between the wetland and the river last week. The final sequence actually started a little unexpectedly, as Amy Ammer watched silty Columbia River water wash in.

Scientists are focusing salmon restoration efforts on wetlands near the Columbia's mouth.

Amy Ammer: "Our plan was to remove the coffer dam and then have the tide go in. The tide's high enough that it came around and helped itself to our project site."

After the tide forced its way past the coffer dam, crews methodically removed the vertical pieces that had kept the river water out.

As Ammer waited for that work to finish, she emphasized the importance of connecting the wetland near Fort Columbia.

Amy Ammer: "This is kind of those types, you know the 'golden goose' - high quality habitat, fully disconnected, connected again to the Columbia River. And this particularly area, because we're in the brackish area, it's particularly important life history stage for salmon as they're transitioning from fresh to salt."

The $1.2 million project provides fish channels and tree trunks, and promises a salt-and-freshwater mixing zone covering 12 acres.

Salmon could wind up using the whole 96-acre wetland. Ammer says because of the new 12 foot-by-12-foot entrance, salmon will have a wetland that's more like what the Corps of Discovery found 200 years ago.

Amy Ammer: "One of the things that I have at my desk is a map of this. When they came through here, they did map it. And that was part of the impetus for saying 'hey, we do have a good project', because this is an historic distributary. And it would've been connected. This highway causeway wasn't built by nature."

Historians say that Lewis and Clark likely mapped the wetland from the edge, without walking into the bog on foot. Until the last few years, federal agencies didn't look too closely at the estuary, either.

Now, BPA is playing catch up. Officials are trying to expand scientific understanding of the lower river wetlands, while also funding recovery projects there.

But a scientific review panel has raised questions about that approach, arguing BPA doesn't have a scientifically rigorous way of prioritizing projects for federal funding.

Staff at the Northwest Power and Conservation Council summarized those concerns last month by saying "the mechanisms for project selection and evaluation in the estuary are not functioning."

It went on to say that a "intervention" was needed.

Tony Grover directs fish and wildlife for the council.

Tony Grover: "I think it's fair to say that the lower river and estuary is about 25 years behind the rest of the Columbia Basin in developing a set of routine procedures to screen projects and develop them."

Tony Grover says one of the main barriers to good research is pretty basic. He says scientists are used to using structures like dams to count and track fish, but they haven't yet figured out how to do that in an estuary environment.

Tony Grover: "There's no place where the fish congregate below Bonneville Dam in sufficient numbers that would make it efficient to set that kind of a system up."

BPA says it's working with the Army Corps of Engineers and scientists to come up with a better system by the end of the year.

Back at the estuary restoration project, there's a narrow window for getting the work done. Amy Ammer with CREST says the in-river work can only happen in the winter, when the fish aren't using it.

Amy Ammer: "The reason is you have adults coming in the fall, and you have juveniles going out in the spring, summer, fall. And you have adults coming at different times, as well - spring, summer, and fall - pretty much all the time. This is the time when there's the least amount of fish."

So as contractors get their equipment in place and scientists get their monitoring systems ready this fall and winter, they might feel a little like Lewis and Clark did.

It was in late fall 1805 that William Clark wrote of a boggy bay, and a Dismal Nitch, at the mouth of the Columbia.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum