forum

library

tutorial

contact

Scientists Survey Pacific Northwest Salmon Each Year.

For the First Time, Some Nets are Coming Up Empty.

by Lynda V. Mapes

Seattle Times, October 9, 2017

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Scientists Survey Pacific Northwest Salmon Each Year.

by Lynda V. Mapes

|

Surveys off Washington's coast detected low numbers of juvenile salmon from the Columbia River,

including spring chinook, a bad omen for orcas and other species that rely on the king of fish.

Scientists have been hauling survey nets through the ocean off the coasts of Washington and Oregon for 20 years. But this is the first time some have come up empty.

Scientists have been hauling survey nets through the ocean off the coasts of Washington and Oregon for 20 years. But this is the first time some have come up empty.

"We were really worrying if there was something wrong with our equipment," said David Huff, estuarine and ocean ecology program manager in the fish ecology division at NOAA Fisheries. "We have never hauled that net through the water looking for salmon or forage fish and not gotten a single salmon. Three times we pulled that net up, and there was not a thing in it. We looked at each other, like, ‘this is really different than anything we have ever seen.'

"It was alarming."

Moving from Newport, Oregon, to the northern tip of Washington, anywhere from 25 to 40 nautical miles offshore last spring and summer, the survey team began catching fish -- but not the ones usually in those waters. Instead, warm-water fish, such as mackerel -- a predator of young salmon -- and Pacific pompano and pyrozomes -- normally associated with tropical seas -- turned up in droves. Both deplete the plankton that salmon need to survive.

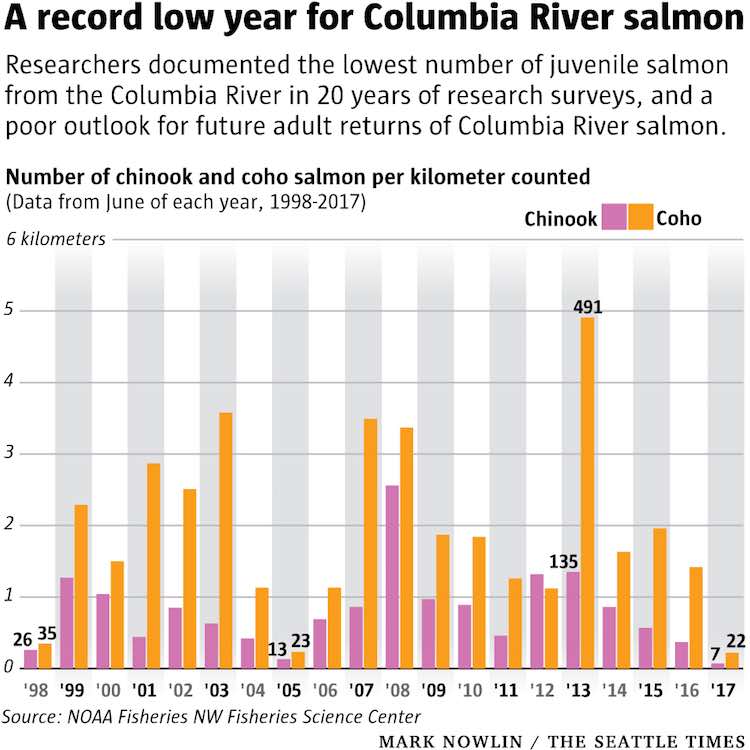

In a report on their trawl survey, the scientists logged some of the lowest numbers of yearling Snake River spring chinook recorded since the survey began in 1998. Coho numbers were just as depressed.

"Every year is different. But this year popped out as being really different," said Brian Burke, a research fisheries biologist based at the NW Fisheries Science Center in Montlake. "Not just a bunch of normal metrics that point to a bad ocean year, but the presence of these things we have never seen before, really big changes in the ecosystem. Something really big has shifted here."

It's not a short-term problem.

Low survival of juvenile salmon also portends a paltry return of adult salmon in two years and longer into the future -- bad news for animals that depend on salmon for their own sustenance. Especially southern- resident killer whales, already at a 30-year low in their population, following the recent death of an emaciated calf.

While its body was not recovered, so the cause of the calf's death cannot be certain, starvation makes the orcas' other challenges, from vessel noise to toxic pollution to disease, harder to fight off.

This year's bizarre survey results all started with The Blob, as it came to be known: an enormous mass of unusually warm water off most of the West Coast that beginning in 2013 wreaked havoc with species survival and food abundance in the ocean.

Now the blob is gone, but some of the animals that came north with it, vastly expanding their range, are still here.

The survey demonstrates the value of direct sampling, and long-term data sets. Satellite imagery shows a return to normal water temperatures by now along the West Coast. It was only by getting out with their nets and pulling trawl samples -- and having a long-term data set against which to compare results -- that scientists realized the disruption that is still very much underway.

The interrelated nature of the ecosystem means those disruptions have far-reaching effects.

Pacific pompano and jack mackerel used to be scarce off the Northwest Coast. But their abundant presence now has indirect and direct effects on salmon.

Researchers also found plankton with less of the fatty nutrients that young salmon need, starving the food chain from its first link. Chlorophyll, the indicator of plankton that stoke the higher levels of life in the sea, also is at its lowest levels recorded in 20 years.

Tiny marine crustaceans called copepods that spell fat city for salmon have also been at depressed populations since 2014. The jelly- fish community is upside down, too, with a complete shift underway from predominantly Pacific sea nettle, to the much smaller water jelly.

Critical forage fish that support a wide range of species -- including herring, anchovies and smelt -- also are scarce.

That could force predators that usually would feed on them to eat salmon instead. Birds that gather just north of the Columbia River mouth, such as common murre and sooty shearwater, may have turned to yearling salmon to fill their bellies, with their usual fare of forage fish so depleted. That, in turn, could have substantially increased mortality for juvenile salmon just as they reached the ocean.

That would explain why researchers sampling salmon populations in the estuary didn't find the same stark and troubling scarcity the ocean researchers did, Burke noted.

And why what fish the ocean researchers did catch in their trawl nets looked well. "We did not see skinny fish," Burke said.

While the research is still being finalized, it signals likely lean times ahead for salmon fishers, human and non. That's bad news for southern-resident killer whales, which just won't switch to other prey, even when their preferred food -- chinook salmon -- are scarce. Their diet is culturally embedded in teachings reinforced in intergenerational family clans. The result is that orcas, so far, are starving rather than switching to seals and the other marine mammals that orca whales elsewhere devour.

Huff said the purpose of a memo the research team wrote to managers about their survey results was intended to provide an early warning of how poor and just plain strange conditions in the ocean off Washington and Oregon's coasts are.

The findings also underscore the powerful role the ocean plays in salmon survival, as well as the importance of creating and maintaining good freshwater habitat, to help salmon deal with the vagaries of the sea.

It's not clear what will happen next. "It takes some time to find that out," Huff said. "Sometimes things don't recover right away. If at all. Only time will tell."

Related Pages:

UW Professor's Study Links

Food Scarcity to Orcas' Failed Pregnancies by Lynda Mapes, Seattle Times, 6/28/17

As the Chinook Go, So Go the Orcas by Peggy Andersen, Seattle Times, 4/5/6

World's Oldest Known Killer Whale Granny Diesby Victoria Gill, BBC News, 11/3/16

Related Sites:

Fisheries Canada: www.pac.dfo-mpo.gc.ca

National Marine Fisheries Service: www.nwr.noaa.gov

Orca Network: www.orcanetwork.org

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum