forum

library

tutorial

contact

Get Rid of Dams to Save Salmon?

Not So Fast

by Kurt Miller

Idaho Statesman, October 1, 2019

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Get Rid of Dams to Save Salmon?

by Kurt Miller

|

Make no mistake, wild Chinook are in trouble.

Make no mistake, wild Chinook are in trouble.

They're not alone either. As a whole, salmon and steelhead are struggling, and historically speaking, they have been for a long time. Recently, the New York Times covered this struggle in an article they published entitled, "How long before wild Chinook salmon are gone? 'Maybe 20 Years.'"

Indeed, the concerns over the future of wild Chinook and other salmon is valid. This is especially the case for populations that are listed as threatened or endangered, including those in Idaho.

I largely agree with the concerns that Jim Robbins, the author of the article, raises about the future that lies ahead for salmon. However, I am not alone when I say that he is misinformed about the following statement, which serves as the foundation of his article. Mr. Robbins writes,

"Before the 20th century, some 10 million to 16 million adult salmon and steelhead trout are thought to have returned annually to the Columbia River system. The current return of wild fish is 2 percent of that, by some estimates.

"While farming, logging and especially the commercial harvest of salmon in the early 20th century all took a toll, the single greatest impact on wild fish comes from eight large dams -- four on the Columbia and four on the Snake River, a major tributary."

This statement gives the impression that the dams on the lower Columbia and lower Snake rivers are primarily responsible for the decline of adult salmon returns in the Columbia River Basin.

There is actually very little debate in the region about the fact that salmon populations were already largely decimated due to the commercial harvest that occurred well before Bonneville dam was completed in 1938.

Articles in local newspapers, including The Oregonian in 1882, describe the overfishing that took place and how it drove salmon populations to near extinction.

Since the completion of Bonneville dam, salmon returns have improved from the mere few hundred thousand annually to over 2 million in 2014, before tapering off in the last several years.

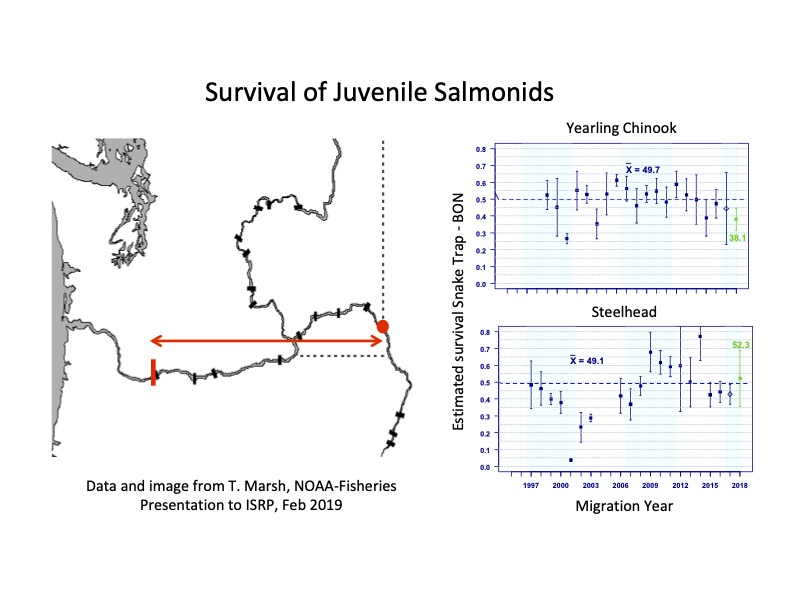

The declines observed since 2014 perfectly mirror degrading ocean conditions as a result of a massive marine heatwave that began that year and lasted for over three years.

Mr. Robbins also acknowledges the threat of poor ocean conditions, but also states that, "those who want to keep the dams point to changing ocean conditions as a major factor in the decline of the salmon." This implies that ocean conditions are a talking point rather than a legitimate issue.

There is, however, a wealth of science that has consistently shown a direct tie between ocean temperatures and the number of returning adult salmon. The higher the temperature, the worse the runs will be.

Warming temperatures in oceans and rivers as a result of climate change and human activity have raised the acidity of the water, decreased oxygen levels, and reduced the availability of critical prey for salmon.

A recently released special report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change states that, "the ocean has taken up more than 90% of the excess heat in the climate system," and warns of the impacts this has on the abundance of marine life and fish populations, especially in coastal areas.

Should this trend continue, and the temperatures continue to rise, salmon indeed certainly face an uncertain future.

The idea of pulling out renewable resources, like the lower Snake River dams, threatens to only worsen the severity of climate impacts.

The calls for dam breaching also ignore the fact that the dams help us add other renewable resources.

Solar and wind are very important as we fight our contribution to climate change, but they are intermittent. Hydroelectric dams are essential because they can quickly "turn on and off" to help balance the grid.

Simply put, hydropower partners with solar and wind to provide a consistent power supply in a completely carbon-free way.

When we discuss the place of the lower Snake River dams, we need to look at these issues holistically. An oceanwide problem requires a solution that addresses the ocean and a climate problem requires a climate-based solution.

Ultimately, I believe in science-based solutions for salmon, and like Mr. Robbins, I am deeply concerned about the future for wild Chinook and other salmonids. I am also concerned that while the fight continues over the dams, we are ignoring the real threat to the future of salmon in the Columbia River Basin and the entire North Pacific Coast. Our time to act is running out.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum