forum

library

tutorial

contact

Leave Dams on Snake

and Columbia Rivers in Place

by Editorial Board

The Daily News, August 11, 2020

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Leave Dams on Snake

by Editorial Board

|

The report acknowledges that removing the dams

would provide the runs the best chance of recovering.

For centuries, humans have done much to destroy the Columbia River's storied salmon runs.

For centuries, humans have done much to destroy the Columbia River's storied salmon runs.

We have fished them to exhaustion. We have polluted and trashed the waterways where they hatch and return to spawn. We have erected hydroelectric dams that impede their migration to and from the sea. We have so disrupted the environment that critters now maul them at every stage of their life cycle. Lastly, we have changed the climate and warmed up the oceans where they fatten up and grow into adults.

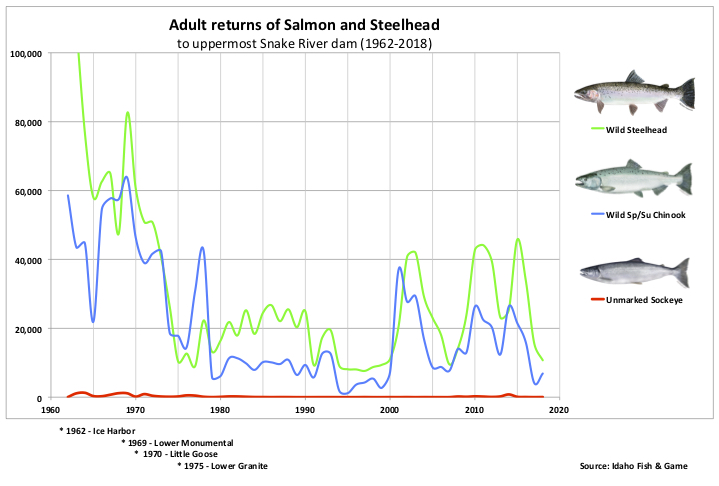

It's a wonder they have survived at all. A river system that once produced 5 million to 16 million returning adult salmon annually now sees only about 2 million, and nearly half of those are born in hatcheries. More than half of the stocks are listed under the federal Endangered Species Act. And other wildlife feeding on them, such as the Puget Sound orca population, suffer the consequences.

This region's electric ratepayers have invested billions of dollars trying to "recover" the runs, with mixed results so far. So it might be understandable that conservation groups and regional tribes have long advocated, in our view, an extreme measure: breaching the four lower Snake River dams.

Late last month, three federal agencies that oversee operation of the Northwest's hydroelectric dams released "final" recommendations on how best to preserve threatened and endangered runs of salmon and steelhead on the Snake and Columbia rivers.

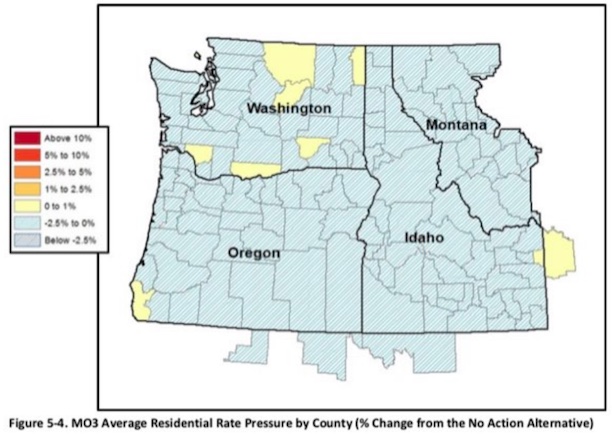

Their 5,000-page report recommends leaving the four lower Snake dams in place, instead using increased spill of water at the larger upstream dams during spring and early summer to aid the passage of juvenile fish on their way down river to the Pacific Ocean. Increasing spill during times of low demand for electricity would reduce the number of fish killed in turbines and screens.

The report acknowledges that removing the dams would provide the runs the best chance of recovering. And it also admits its "flexible spill" plan would only preserve but not rebuild fish numbers. However, it says removing the dams would disrupt the region's power supply, drive up shipping costs for commodities such as wheat, and double the risk of regional power outages.

We agree.

We agree.

Salmon runs were already in steep decline before the Snake River dams were built in the 1960s and 1970s. High summer water temperatures -- which conservationists cite to justify dam removal -- were a problem for salmon long before the dams were built. Snake River Chinook runs, as weak as they are, are stronger now than they were before three of the four Snake dams arose, according to the report.

Agencies have worked diligently to improve downstream juvenile salmon passage through the dams. More spills of water and installation of screens to divert the fish from deadly trips through the turbines have dramatically improved salmon survival. At least 93% of the fish survive the downstream passage at each of the Snake and Lower Columbia River dams, according to the report.

Losing the hydroelectric power of those four dams would be a problem because the region is due to decommission 2,500 megawatts of coal-generated power in the next decade. That's the output of two nuclear plants.

And the dams are strategically located in the eastern half of the Pacific Northwest, helping ease power transmission limits.

(bluefish notes: The EIS contradicts this editorial comment that Lower Snake River dams "ease power transmission limits." Indeed, the opposite was found to be the case, as reported in the EIS.)

How would we replace that power? More wind and solar are of course possible, but they are variable and have far less reliability and cost much more than hydropower. Do we really want to replace carbon-free hydropower with combustion-based power generation, such as natural gas? Just where is the electricity going to come from to power up all those battery-powered cars we want to help reduce carbon emissions and stop global warming?

Rising power costs due to the need to protect salmon already have contributed to the shut down of the region's aluminum industry and undercut one of our incentives for attracting new industry: low-cost electrical power.

The report notes that the Snake River dams are among the most cost-effective in the entire Columbia River hydroelectric system. And they offer competitive advantages for farmers and lower river ports to ship wheat and other commodities through navigation locks of the Snake and Columbia River dams.

Breaching the four lower Snake River dams would be costly, disruptive and probably would not result in dramatic fish recovery. At a certain point, the expense and hardship will erode public support for salmon and other conservation efforts.

(bluefish notes: This editorial contradicts itself, "The report acknowledges that removing the dams would provide the runs the best chance of recovering. And it also admits its 'flexible spill' plan would only preserve but not rebuild fish numbers." (see bold text above))Dam removal also could set a precedent. When would the dam breaching on the Columbia River system stop?

Low-cost hydropower led to the development and expansion of the Pacific Northwest. It's part of our economic lifeblood. We can't turn back the clock, especially when we're trying to get control of climate change, which is itself a grave threat to salmon and the web of life that supports them and many other critters.

Like all environmental problems, recovering the salmon is a complex scientific and public policy challenge. Steps have been taken. More are needed. But breaching the lower Snake River should not be among them.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum