forum

library

tutorial

contact

Puget Sound Orcas' Plight

Linked to Snake River Dam Removal

by K.C. Mehaffey

NW Fishletter, September 4, 2018

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Puget Sound Orcas' Plight

by K.C. Mehaffey

|

"There's a sense of bewilderment of why creating goals is important."

Some orca proponents say recovering Chinook runs in the Snake and Columbia rivers through increased spill and removal of the four lower Snake River dams is a vital component to saving southern resident killer whales from extinction.

Some orca proponents say recovering Chinook runs in the Snake and Columbia rivers through increased spill and removal of the four lower Snake River dams is a vital component to saving southern resident killer whales from extinction.

However, NOAA Fisheries scientists maintain that recovering salmon stocks throughout the killer whale's entire range, from Northern California to Canada, is important and that no single basin will save the whales.

The agency also says hatcheries produce more than enough Chinook--the pod's main prey--in the Columbia and Snake rivers to offset any losses caused by dams.

The focus on Columbia River Basin dams comes as the population of 75 killer whales that summer in Puget Sound attracted international attention when a mother whale gave birth to a calf, which died in less than an hour.

For more than two weeks, the mother was seen pushing her baby to the surface in what some observers have interpreted as a demonstration of her grief. During that time, biologists noticed a 3-year-old female in the pod was emaciated, and attempted to feed her, provide her with medicine and observe her condition continue.

Efforts to recover this population of killer whales have been underway for several years. Southern residents were initially listed as endangered in 2005, and NOAA Fisheries completed a recovery plan in 2008.

This year, in March, Washington Gov. Jay Inslee signed an executive order forming a task force to develop an action plan to recover the whales and ensure a sustained population into the future.

Both NOAA Fisheries and the governor's proclamation identify three primary causes of the orca's decline: prey availability, toxic contaminants, and disturbance from noise and vessel traffic.

NOAA spokesman Michael Milstein said none of the three problems are considered a leading cause of the orca's decline.

"We think they're all essentially important in different ways," Milstein said. In some cases, the problems compound one another. For example, he said, "When there's a lot of ship noise, whales can't use their echolocation to find fish," so in that case, the availability of prey is secondary.However, a July 31 news release from the Orca Salmon Alliance claims, "An extreme shortage of prey--primarily Chinook salmon--is the leading cause for their decline in recent years."

Joseph Bogaard, executive director of Save Our Wild Salmon Coalition, which is part of the Alliance, said food is a daily need, and if the whales had enough prey, impacts of vessel noise and toxins wouldn't be as severe.

"The fact that there aren't many fish means the vessel issue is worsened," Bogaard said. Toxins, too, are more of a problem for the whales because they don't have enough to eat, since whales store toxins in their blubber, and when they don't have enough food, they start burning up the blubber." If we were able to get those guys a lot more food, in the near term, then those other issues would not go away, but they're lessened," he said.

The Alliance news release said the whales should now be foraging on Fraser River salmon, and that research has shown a direct correlation between the size of the Fraser River salmon runs and the presence of southern residents in their core summer habitat, the San Juan Islands and surrounding waters and the mouth of the Fraser River near Vancouver, British Columbia.

The news release also says southern residents have, at best, five more years of reproductive potential, and that urgent actions are needed to improve Chinook salmon stocks throughout their range, from central California to British Columbia, and "especially the Columbia-Snake River system."

"The Columbia basin was once the most productive salmon basin on the planet. It produced upwards of 20 million fish returning as adults every year," Bogaard said. He said in the populous Salish Sea basin, it will take a complicated approach to restore salmon habitat. But in the Columbia and Snake rivers, he said, "The restoration potential is really high," he added. "Upstream, it doesn't need to be restored. It needs to be effectively reconnected to provide salmon access."

While the Alliance's news release does not mention removing dams or spilling more water, the Save Our Wild Salmon Coalition is pushing for Inslee's task force to include both measures in its recommendations.

In an Aug. 7 statement, the Coalition said Washington state should work with Oregon and federal dam managers to increase spill to 125 percent of total dissolved gas at the lower Snake and lower Columbia river dams, beginning in 2019.

And, the statement said, Inslee should support removal of the four lower Snake River dams to provide better access to thousands of miles of prime salmon habitat.

The push for more spill and dam removal on the Snake River doesn't sit well with Terry Flores, executive director of Northwest RiverPartners. "If people are genuinely serious about helping orcas--which I hope we all are--using spill or dam removal is not helpful to the orcas," she said. "We are in complete agreement that this iconic species should not go extinct on our watch, or anyone's watch. And what that means is, you really need to focus and [home] in on those things that have some scientific basis, and can be accomplished quickly," she said.

Flores said that there's no scientific basis for claiming that additional spill or removing lower Snake River dams will improve Chinook runs. And, removing the dams would take far too long to make a difference. She said some groups with a long-held agenda to remove the Snake River dams appear to be using this emotional issue to advance their goals. "I find that disheartening because it simply doesn't help the orca situation, and if anything, it undermines it. It distracts from potential solutions that could be implemented in the short term," she said.

Bogaard said historically, the Snake River produced roughly half of the basin's spring Chinook. He said removing the lower Snake River dams would allow more adults and juveniles to pass the dams and survive, and help cool water temperatures. He acknowledged removing the dams would take years, but a decision now would put the whales on a path to recovery. "It's not a decision for the governor to make," he said, "but he's in a position to bring stakeholders together and say, 'This is what we need to do.'"

But scientists at NOAA Fisheries say that, while Snake River Chinook are part of the whale's diet, they are not the only or most important part. Milstein said scientists don't know what percentage of the orca's diet consists of Snake River Chinook. He said a recent study rating 31 Chinook stocks that southern resident orcas consume highlights the importance of all the stocks, because they rely on different runs at different times of the year.

Milstein said the Fraser River in British Columbia and rivers emptying into Puget Sound have long provided orcas with a major source of Chinook, especially because the whales have access to those areas much of the year. But, he added, "It's not about any one river, it's about the diversity of rivers and stocks over the course of any year. It's not intended to show that one stock is more important. It's about how much of a role each one plays in their food supply and survival."

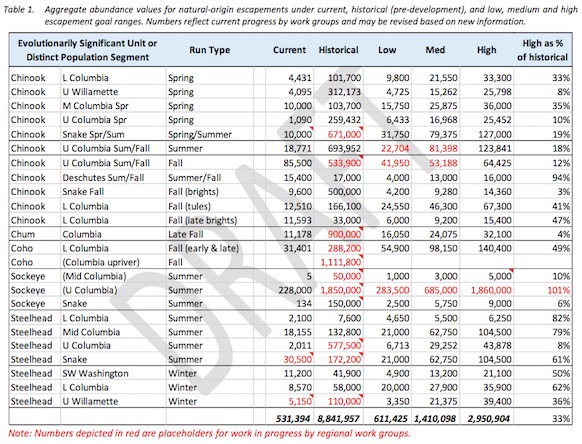

More importantly, Milstein said, the Snake River is a bright spot in terms of production of Chinook salmon, when hatchery fish are included. Numbers of returning adults--both wild and hatchery--passing Lower Granite Dam hovered around 50,000 fish in the 1960s and early 1970s, and then suffered declines until about 2000, when hatchery fish began to fill in the losses. Average returns from 2005 through 2015 totaled more than 92,000 adults. Similarly, fall Chinook passing Lower Granite Dam have increased dramatically since the 1970s, and in recent years have numbered between 30,000 and 60,000 adults. The numbers represent escapement after harvest and losses to predators.

Milstein added there's no indication the orcas prefer wild Chinook over hatchery fish. "Essentially, the whales have access to as many or more fish from the Columbia River Basin as they would have otherwise," he said. "And hatchery fish have been documented in their diet. They prey on both," he said.

This isn't the first time groups have eyed the lower Snake River dams in relation to orca recovery. A 2016 NOAA Fisheries fact sheet outlines the issue, and Milstein said his agency's position hasn't changed since then.

"We think all of these stocks are important, and we're moving with a lot of different partners to recover them, through a lot of different means, whether it's managing hatchery production in a way that protects wild fish, managing harvest to the extent that we can make a difference, and dam passage, which is much improved," he said.

K.C. Mehaffey

Puget Sound Orcas' Plight Linked to Snake River Dam Removal

NW Fishletter, September 4, 2018

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum