forum

library

tutorial

contact

Removing Dams, Restoring Rivers

by Elizabeth GrossmanEnvironmental News Network, December 7, 1999

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Removing Dams, Restoring Riversby Elizabeth GrossmanEnvironmental News Network, December 7, 1999 |

"Salmon are now extinct

in almost 40 percent of

the rivers in which they

historically spawned in

Oregon, Washington,

Idaho and California,"

according to fisheries

biologist Jim Lichatowich.

"The salmon populations

in 44 percent of the

remaining streams are at

risk." Twenty-six distinct

populations of Pacific

salmon are now listed

under the Endangered

Species Act. Many factors

have contributed to the

decimation of Pacific salmon, but the most obvious impediments to their natural

survival are dams.

"Salmon are now extinct

in almost 40 percent of

the rivers in which they

historically spawned in

Oregon, Washington,

Idaho and California,"

according to fisheries

biologist Jim Lichatowich.

"The salmon populations

in 44 percent of the

remaining streams are at

risk." Twenty-six distinct

populations of Pacific

salmon are now listed

under the Endangered

Species Act. Many factors

have contributed to the

decimation of Pacific salmon, but the most obvious impediments to their natural

survival are dams.

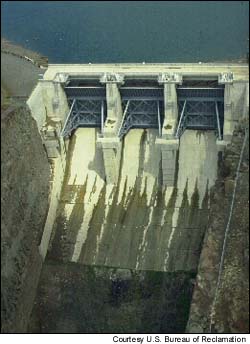

Serious dam building began with the European settlement of the Northwest. More and bigger dams were built without real knowledge of their devastating effect on anadromous fish. Now, in an attempt to restore native fish runs at what may be the Pacific salmon's 11th hour, dams in the Northwest are beginning to come down.

On Nov. 8, Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt announced plans to remove five Pacific Gas and Electric Company dams, and restore chinook salmon and steelhead in Battle Creek, a major Sacramento River tributary in northern California. The $50.7 million Cal-Fed project involving state and federal agencies and local conservation groups calls for new fish protection on several other Battle Creek dams. If successful, this will be the first such stream in California where salmon will be able to return to their historic spawning grounds.

"Wild salmon," said Babbitt in a press statement, "are not merely commodities," but "vital members of creation who enrich our lives and landscapes."

Removal of another obstacle for salmon, on the Elwha River on Washington's

Olympic Peninsula, was announced on Oct. 20. The agreement reached by Babbitt,

Sen. Slade Gorton, R-Washington, and Rep. Norm Dicks, D-Washington, allows the

federal government to purchase and plan demolition of the Elwha and Glines

Canyon dams. Both dams lack fish ladders and have thus blocked the river's salmon

runs since completion of the second dam in 1927. Babbitt and Dicks want both dams

removed, but Gorton would delay removal of the Glines Canyon dam. He questions

"whether the results are going to be worth" the estimated $60 million the project

will cost.

Removal of another obstacle for salmon, on the Elwha River on Washington's

Olympic Peninsula, was announced on Oct. 20. The agreement reached by Babbitt,

Sen. Slade Gorton, R-Washington, and Rep. Norm Dicks, D-Washington, allows the

federal government to purchase and plan demolition of the Elwha and Glines

Canyon dams. Both dams lack fish ladders and have thus blocked the river's salmon

runs since completion of the second dam in 1927. Babbitt and Dicks want both dams

removed, but Gorton would delay removal of the Glines Canyon dam. He questions

"whether the results are going to be worth" the estimated $60 million the project

will cost.

The Condit, another Washington state dam, blocking fish passage on the White Salmon River, a tributary of the Columbia known for its whitewater rapids, is also slated for demolition. The Condit's removal, due to begin in 2006, was announced in September by the dam's operator, PacifiCorp, the Yakama Nation, Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, American Rivers and state and federal agencies. The final years of the dam's operation will generate some of the project's $17.15 million budget. Talks between stakeholders began nearly 10 years ago when it was discovered that bringing the dam up to environmental standards would make its operation unprofitable.

While restoration of fish runs on other Northwest rivers progresses, contentious

debate — some would say a stalemate — over the four lower Snake River dams

continues. Communities whose livelihoods have come to depend on the benefits of

the lower Snake dams, particularly irrigators, those who ship goods by barge and

whose jobs have grown up with these industries, fear that altering current use of

the dams will mean severe economic hardship. Yet studies by American Rivers, Trout

Unlimited and EcoNorthwest exploring alternatives to current uses of the river are

under way and have shown their costs to be no greater than the cost of

subsidizing, maintaining and operating the dams.

While restoration of fish runs on other Northwest rivers progresses, contentious

debate — some would say a stalemate — over the four lower Snake River dams

continues. Communities whose livelihoods have come to depend on the benefits of

the lower Snake dams, particularly irrigators, those who ship goods by barge and

whose jobs have grown up with these industries, fear that altering current use of

the dams will mean severe economic hardship. Yet studies by American Rivers, Trout

Unlimited and EcoNorthwest exploring alternatives to current uses of the river are

under way and have shown their costs to be no greater than the cost of

subsidizing, maintaining and operating the dams.

Only months ago, the National Marine Fisheries Service called removal the best way to restore the Snake's endangered fish. Yet, in a document recently released, NMFS emphasizes the restoration of spawning habitat instead of dam removal. Meanwhile, ruling is awaited on a lawsuit filed by a coalition led by the National Wildlife Federation, charging that the dams violate the Clean Water Act by raising water temperatures and levels of dissolved gas. An EPA study recommends partial removal in order to cool Snake River temperatures sufficiently for healthy fish runs. It remains to be seen if bringing back Columbia Basin salmon will include the restoration of natural conditions on the lower Snake, or if dams will continue to be a permanent part of the landscape.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum