forum

library

tutorial

contact

Sockeye Get Their Wildness Back

by Rocky BarkerIdaho Statesman, November 24, 2014

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Sockeye Get Their Wildness Backby Rocky BarkerIdaho Statesman, November 24, 2014 |

In his essay "Walking," Henry David Thoreau wrote, "In Wildness is the preservation of the World." That sentiment grew into the philosophical foundation on which the modern environmental movement was built.

In his essay "Walking," Henry David Thoreau wrote, "In Wildness is the preservation of the World." That sentiment grew into the philosophical foundation on which the modern environmental movement was built.

"From the forests and wilderness comes the tonics and barks which brace mankind," Thoreau wrote. The farther from wildness we get, he was telling us, the weaker and less fit we are to handle the sickness and adversity nature throws at us.

Biologists have long been able to actually measure the value of this wildness genetically. Species with genetic diversity, developed in the wild often over thousands of years, display more fitness, more ability to survive, than those species that lose diversity through a natural or human-caused event,

Studies have shown, for instance, that it takes salmon five generations to restore this fitness, or wildness, if raised in a hatchery and returned to the wild to spawn.

Idaho saw this happen once. Sockeye salmon were cut off from their spawning grounds in Redfish Lake when Sunbeam Dam was built in 1911. When the dam was removed in 1931, sockeye began returning to Redfish, almost miraculously.

They likely came from the resident sockeye that biologists later learned lived and spawned in the lake, a few every year heading downstream looking for the Pacific. The sockeye thrived until the late 1950s, when the final dams were built on the Snake and Columbia rivers. By the early 1990s, Lonesome Larry and 15 other sockeye were taken into captivity - all that was left of the natural sockeye population.

In 2006, geneticists questioned whether the sockeye-restorationprogram was worth the money. They worried that there wasn't enough genetic diversity left to produce salmon that could survive the rough life in the Pacific and the 900-mile migration from Redfish to the ocean and back.

Even if the four dams on the Lower Snake River were removed, which some fisheries biologists still believe is necessary to recover the sockeye, the fish might need five generations to get back their fitness to survive, the geneticists argued.

Paul Kline, the assistant chief of fisheries at the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, never gave up his belief in their genes.He was able to bring the rest of the Pacific Northwest along with him. A new paper published in the journal Fisheries by Kline and Thomas Flagg of NOAA Fisheries shows that his faith paid off.

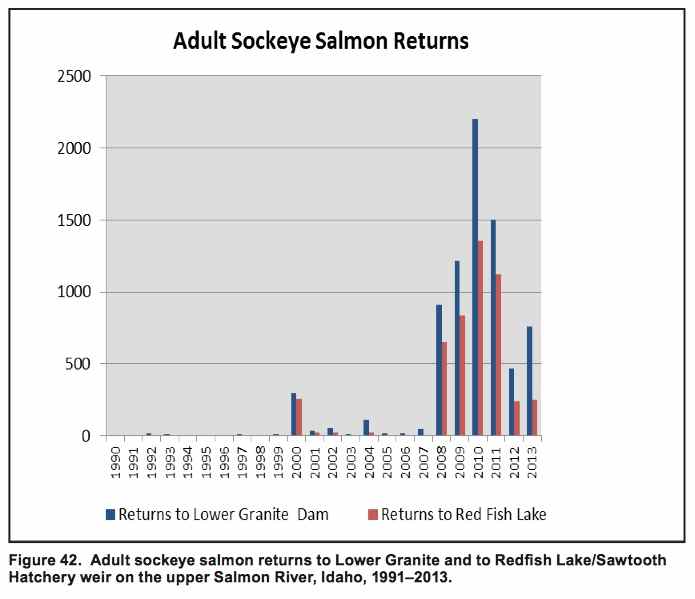

Naturally spawning sockeye today return at a rate three times higher than smolts raised in the hatchery and released in the rivers and at 10 times the rate of hatchery-raised sockeye placed in the lake. The naturally spawning sockeye are producing at least one offspring - and some years averaging two - that make the return trip to Redfish. That means the population is more than replacing itself in only one generation in the wild due to the techniques used.

It is still too early to declare success, but the results suggest the sockeye program has restored the fitness - yes, the wildness - in the sockeye in just one generation.It's a feat that Columbia tribal biologists are reaching in some of their own restoration programs, though perhaps not as quickly.

All of these programs will be tested in the next few years, as cycles in the Pacific Ocean change to warmer temperatures off the Northwest, conditions that can reduce food, increase predators and cut salmon production by a magnitude of 10.

But the success of the sockeye, which in 1990 only Idaho's Shoshone-Bannock Tribes cared to fight for,provides hope for a larger world facing a future biological bottleneck in climate change.

Perhaps what we are learning will help us restore some of the wildness we are destined to lose as ecosystems change or disappear. It may be, as Thoreau said, our preservation.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum