forum

library

tutorial

contact

Solar Energy Shakeout:

Concentrating vs. Photovoltaic

by Ken Wells and Mark Chediak

Bloomberg Business Week, November 14, 2013

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Solar Energy Shakeout:

by Ken Wells and Mark Chediak

|

Sometime next year, BrightSource Energy's $2.2 billion Ivanpah solar power station will become fully operational and begin feeding enough green electricity to California's two largest utilities to power 140,000 homes. Located in the Mojave Desert, 45 miles south of Las Vegas, the 392-megawatt plant works like a giant reflector. Its 173,500 computer-guided solar mirror arrays focus sunlight onto three 45-story towers. The heat generated by the sun's concentrated rays boils water inside, creating steam to run electrical turbines. Spread across 3,500 acres of public land, Ivanpah is the largest plant of its kind. It may also be among the last of its kind ever built in the U.S.

Sometime next year, BrightSource Energy's $2.2 billion Ivanpah solar power station will become fully operational and begin feeding enough green electricity to California's two largest utilities to power 140,000 homes. Located in the Mojave Desert, 45 miles south of Las Vegas, the 392-megawatt plant works like a giant reflector. Its 173,500 computer-guided solar mirror arrays focus sunlight onto three 45-story towers. The heat generated by the sun's concentrated rays boils water inside, creating steam to run electrical turbines. Spread across 3,500 acres of public land, Ivanpah is the largest plant of its kind. It may also be among the last of its kind ever built in the U.S.

Ivanpah was one of the projects financed in part by $9 billion in federal stimulus funds President Obama directed toward green energy in 2009. Anxious to comply with requirements that power companies get as much as a third of their electricity from renewable sources within the next decade, utilities in California and other Western states rushed to sign long-term power purchase agreements (PPAs) with developers, including concentrating solar farms such as Ivanpah. At that time, concentrating solar power was favored by many developers over its rival technology, photovoltaic (PV) solar, where panels convert the sun's rays directly into electricity. PV was too pricey, and big projects that relied on the panels required far more land to generate the same amount of power as a concentrating solar plant.

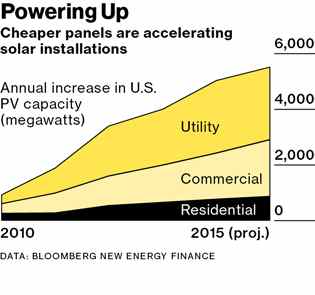

In the last three years, however, the economics have turned decidedly in favor of PV technology. A glut of PV panels, made mostly in China, has pushed their prices down 62 percent since Ivanpah's construction began in 2010, sinking from $1.87 per watt to about 71¢. While at least three other concentrating solar plants are set to join Ivanpah by 2016, many others are being converted to PV or canceled. "Right now, PV is the favored technology," says Ben Kallo, an energy technology analyst with Robert W. Baird, a Milwaukee-based investment bank. "You are getting pretty close to fossil-fuel-type costs with PV technology in about 50 percent of the world, anywhere with high electricity prices and lots of sun." At the same time, "no one's quite mastered concentrating power," Kallo says. Even though the supply glut has diminished, analysts expect PV panel prices to continue to decline, in part because panels are getting more efficient at producing power.

According to the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA), 84 percent of all industrial-scale solar projects under development in the U.S. use PV, while only 16 percent use concentrating technology. The biggest PV plant in the world, with 5.2 million solar panels, is the Agua Caliente station in Yuma County, Ariz. Built by Tempe (Ariz.)-based First Solar (FSLR), the largest solar panel manufacturer in the U.S., the $1.8 billion power plant has a 25-year agreement with Pacific Gas & Electric (PCG) and already adds almost 250 Mw of capacity to the grid. That will rise to 290 Mw once it's completed in 2014.

This shift toward PV has shaken up the industrial-scale solar industry, known as Big Solar, and diminished the triumph of BrightSource getting Ivanpah online. Large photovoltaic plants can now produce power at rates up to 52 percent cheaper than concentrating solar, according to Bloomberg data. "Utilities have very little reason to contract with a [concentrating] solar project when they can contract with a PV project at a cheaper rate," says Stefan Linder, an analyst with Bloomberg New Energy Finance. Earlier this year, BrightSource canceled two multibillion-dollar projects in California that would have employed concentrating solar technology. The company declined to discuss whether it suffered losses on the projects. The one advantage concentrating solar still has over PV is the ability to store power and dole it out at night or on cloudy days. That storage doesn't come cheap, though, and not many concentrating power projects have it. Ivanpah was built without storage to lower costs.

This turmoil has opened the door for what's called distributed generation, where rooftop PV panels generate power that gets consumed close to where it's made. Some 90,000 homeowners and businesses in the U.S. installed rooftop photovoltaic systems in 2012, enough to generate 1.5 gigawatts of power, the equivalent of one large coal-fired power plant. With rooftop installation costs dropping 15 percent a year, an additional 100,000 residential systems could be added by the end of 2013, according to the SEIA. Worldwide, the PV industry may install as much as 42.7 Gw of total capacity in 2013, 40 percent more than in 2012, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance. That includes commercial and residential rooftop systems as well as industrial-scale PV plants. The shift toward distributed rooftop power hasn't yet made a big dent in the profits of large utilities, but they're beginning to feel the bite. Pinnacle West Capital (PNW), whose Arizona Public Service is Arizona's largest utility, recently reported quarterly electricity sales had dropped 1.3 percent from a year earlier, in part due to distributed generation. To head off the threat of rooftop solar, utilities in at least five states have asked regulators to begin taxing rooftop solar installation or tacking on fees to connect to the regular grid in order to recoup lost revenue.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum