forum

library

tutorial

contact

Snake River Dam Removal

Still a Bad Idea

by Andre Stepankowsky

The Daily News, June 15, 2022

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Snake River Dam Removal

by Andre Stepankowsky

|

Perhaps these dams shouldn't have been built half a century ago,

but that's no reason to tear them down today.

Later this summer, Washington Gov. Jay Inslee and United States Sen. Patty Murray will weigh in on a question that has vexed the Northwest for more than a quarter century.

Later this summer, Washington Gov. Jay Inslee and United States Sen. Patty Murray will weigh in on a question that has vexed the Northwest for more than a quarter century.

Should the four lower Snake River hydroelectric dams be breached to help restore endangered and threatened salmon runs?

Here's hoping common sense prevails and the two leaders steer away from that radical and massively expensive idea.

Much is at stake: The four dams generate enough power to supply about 900,000 homes. Their ship locks make it possible to ship grain, wood and other commodities between lower Columbia River ports and the Rocky Mountain region. They are pivotal to operation of the Northwest power electrical grid.

On the other side is the preservation of rugged and once-abundant salmon species that swim 700 miles or more twice in their lifetimes, helped feed generations of native peoples and are an essential part of the river economy and ecosystem.

Federal fisheries managers and hydro system operators repeatedly have rejected the dam breaching idea, and they've been challenged by conservation groups who say hydropower operations jeopardize the fish in violation of the Endangered Species Act.

It's not an easy decision. Few issues are as complex as salmon, especially when their needs collide with the operations of the Northwest hydropower system. Assertions are followed by counter assertions and counter-counter assertions that can leave one bewildered and frustrated.

I've followed this issue for decades, and while my appreciation of the dam-removal argument is more sympathetic, I still oppose the idea. Here's why:

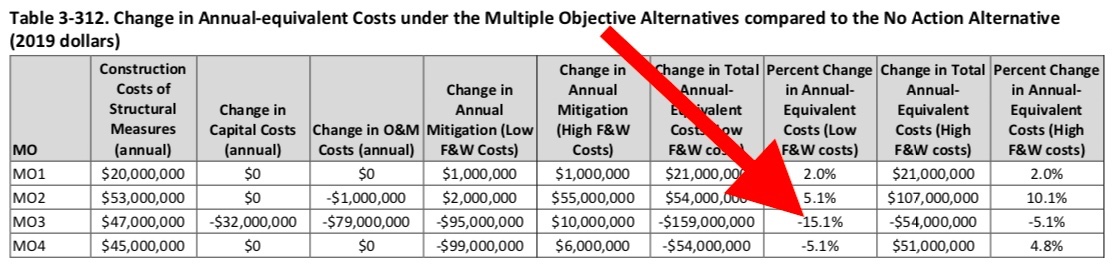

One: The price tag. Removing the dams would cost $1.3 billion to $2.6 billion, and then there are billions of more dollars needed to replace the power they generate.

A report commissioned by the governor and Murray, released last week, estimated that replacing the power, irrigation and transportation capacity the dams now provide would cost $10.3 billion to $27.2 billion.

The money would be better spent on habitat restoration projects, such as the recently completed $32 million project at Steigerwald Lake National Wildlife Refuge east of Washougal, Washington. That 1,000-acre project -- the largest wetland restoration effort completed on the lower Columbia -- planted a half million trees and shrubs and reconnected a creek to the Columbia River. It now provides critical rearing and shelter habitat for juvenile salmon and also benefits many other bird, fish and mammal species.

Imagine how many more of these habitat projects could be funded instead of ripping down the dams.

I doubt a significant number of Northwest electric ratepayers -- who paid for the dams and also would shoulder the cost removing them -- support breaching the structures.

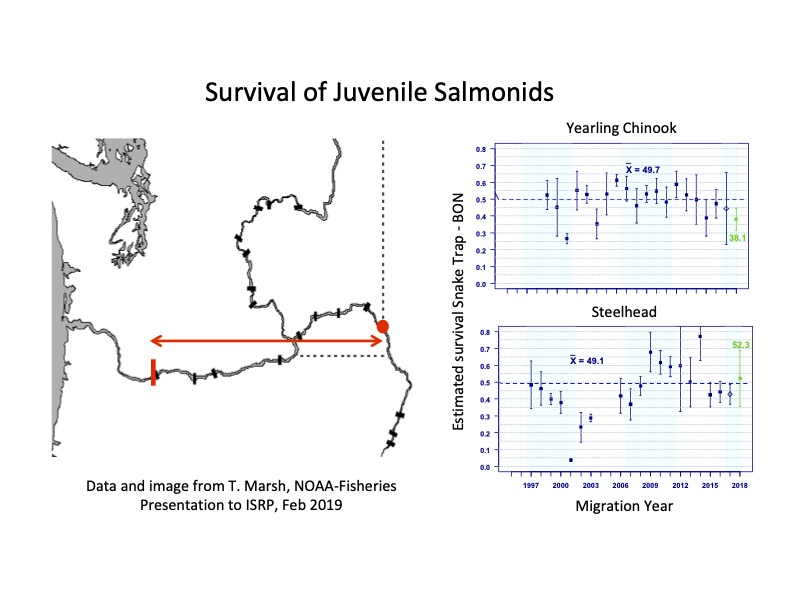

Two: Modifications to the dams to make juvenile salmonids' passage downriver faster and safer -- through turbine screening, additional spills of water and other measures -- have been shown to sharply improve Chinook and salmon survival.

Snake and Columbia rivers' salmon runs improved steadily between 1980 and about 2015, boosted by these passage improvements, tribal hatchery programs and favorable ocean conditions. For example, the 10-year-average return of Chinook at Lower Granite Dam (the uppermost of the four Lower Snake River dams) in 2010 was 83,000, up from 35,000 in 1980). Chinook returns to the Columbia system in 2015 were 1.3 million, a record for a third year in a row.

Runs have collapsed since then as ocean conditions declined.

Nevertheless, history shows the salmon can rebound if other factors -- especially climate and ocean conditions -- cooperate.

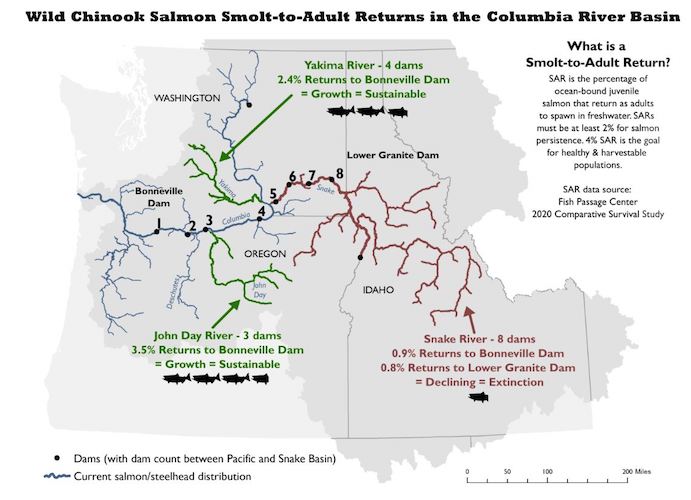

Three: No doubt, removing the dams would help the fish. Some advocacy groups estimate a doubling or tripling of runs is possible.

Yet there's room for skepticism: Even if the dams are removed, the Snake River runs still need to pass through the four lower Columbia dams. The upper Snake River would continue to be blocked off to salmon by the Hells Canyon dams, and the two historically prodigious Snake Basin fish producers -- the Salmon and Clearwater rivers -- already are accessible through fish ladders on the lower dams -- even if some fish advocates' rhetoric subtly implies they are not.

Four: We need the dams' renewable power as we try to wean ourselves off fossil fuels and combat climate change, which is perhaps the greatest threat to salmon. Climate change affects every stage of the salmon life cycle.

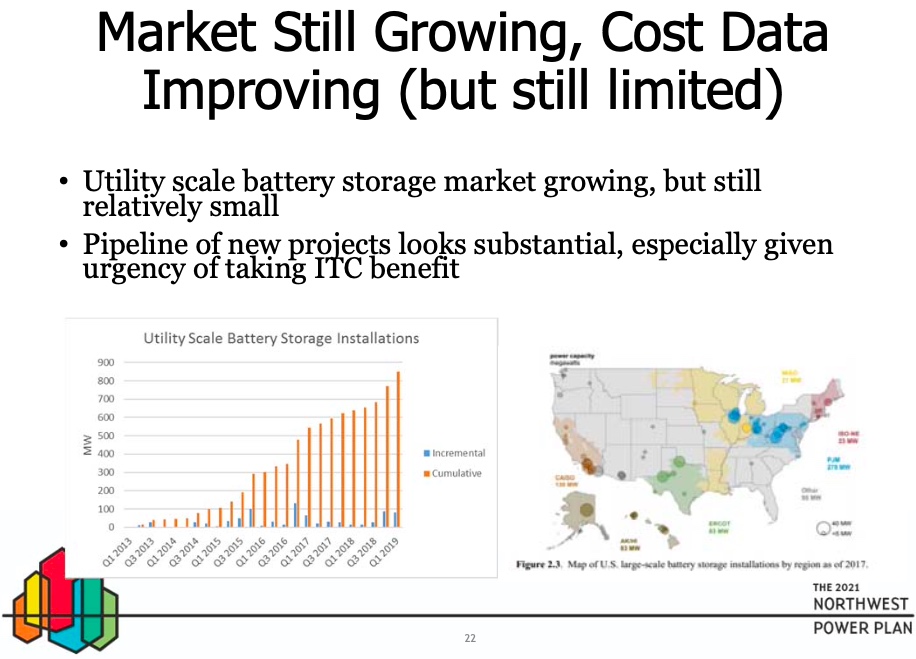

It's true the four Snake dams account for only about 7% percent of the hydropower generated in the Columbia Basin, but every watt will be needed. Northwest energy demand -- flat for two decades -- will zoom as people adopt electric vehicles. The average electric car, for example, uses as much energy as an average home.

Solar and wind are not as reliable as hydropower, even though battery storage technology is advancing and the cost of those sources is declining.

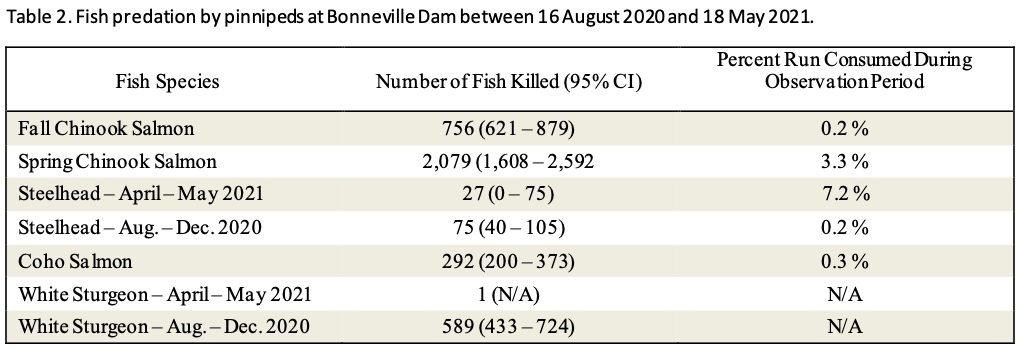

Five: There's still a lot of work to do to reduce predation of salmon by sea lions, cormorants and other species.

Six: The fate of Puget Sounds' Southern Resident Orca population does not hinge on Snake River salmon abundance, despite attempts to link the two. Even if their numbers increased, Snake River chinook would not be a major part of the orcas' food supply, according to federal biologists.

Even if we dismantle a small part of the hydropower system, Columbia Basin salmon runs never will approach their historical highs of 10 million to 20 million returning adults. So what constitutes adequate recovery -- mere survival and perpetuity, or enough abundance to sustain abundant tribal and commercial fisheries?

The choice is made even more difficult because some judgments can't be made with complete scientific certainty, and some factors are beyond human control.

In truth, it's a humbling issue to contemplate. To be sure, perhaps these dams shouldn't have been built half a century ago, but that's no reason to tear them down today.

Andre Stepankowsky retired in August 2020 after a 41-year career as a reporter and city editor at The Daily News. He has won or shared in many prestigious journalism awards, including the staff's 1981 Pulitzer Prize for coverage of Mount St. Helens.

Snake River Dam Removal Still a Bad Idea

The Daily News, June 15, 2022

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum