forum

library

tutorial

contact

Columbia River Fall Salmon Surge, But Endangered

Chinook and Sockeye Runs are Still Struggling

by Casey O'Hara and Keith Ridler

The Oregonian, September 19, 2014

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Columbia River Fall Salmon Surge, But Endangered

by Casey O'Hara and Keith Ridler

|

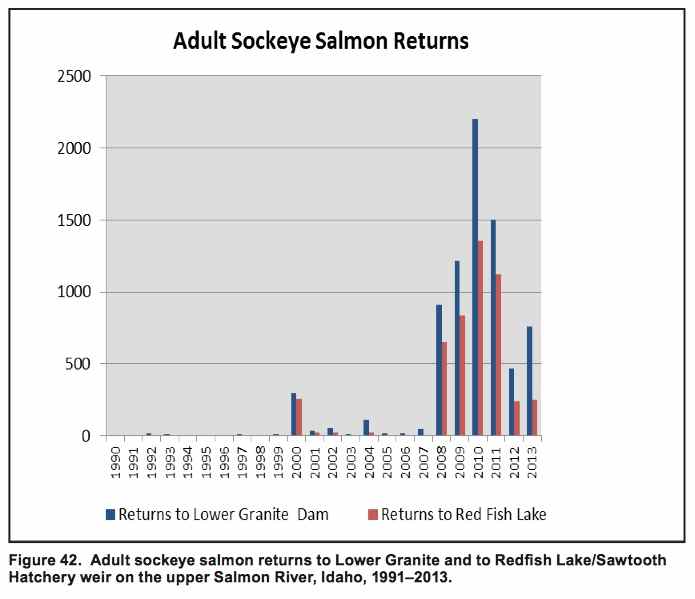

More endangered sockeye salmon have made the 900-mile journey from the Pacific Ocean to central Idaho's high-elevation Redfish Lake this fall than in any previous year going back nearly six decades.

More endangered sockeye salmon have made the 900-mile journey from the Pacific Ocean to central Idaho's high-elevation Redfish Lake this fall than in any previous year going back nearly six decades.

Some 1,400 fish have returned so far from a population that in the 1990s barely survived -- some years with no returning fish -- ultimately becoming the focus of an intense state and federal effort to pull the unique population back from extinction.

The news comes at the same time as Northwest fishery managers report other record, or near-record runs this fall.

More than 600,000 sockeye salmon have leapt Bonneville Dam's fish ladders on the lower Columbia River – most heading to the Okanagan River in north central Washington. And scientists continue to expect a huge fall Chinook run as well, perhaps equaling last year's 1.27 million record.

Most of these fish, however, aren't part of any endangered fish runs.

But the rise in the Redfish Lake sockeye, plus the return of a few thousand imperiled Chinook also heading up the Snake River, is giving scientists, hydropower managers and tribal leaders fresh hope that progress toward recovery is finally being made after decades of divisive litigation.

"As for restoring salmon runs in their entire historic range," said Paul Lumley, executive director of the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission and citizen of the Yakama Nation, "there are so many more things we can do to bring the fish back from where they've been blocked."

At Redfish Lake, fishery managers even envision a potential sport and tribal fishery being discussed within a decade.

"For about 20 years it has operated as a brood-stock program, a safety net program to prevent the extinction of this fish," said Jeff Heindel of the Idaho Department of Fish and Game. "I don't think anybody ever dreamed of where we're at now."

A dam on the Salmon River built in the early 1900s blocked salmon for several decades from reaching Redfish Lake, itself named after the red-colored sockeye that once arrived there in abundance. Additional dams on the Snake and Columbia rivers added to the fish's challenges in succeeding years.

The last time sockeye numbers exceeded the current run was 1955 when 4,361 fish returned to Redfish Lake, Fish and Game records show.

Through recent discoveries made possible by genetic testing, Heindel said, biologists have come to believe that one of the reasons the population didn't blink out in the following decades is due to non-migratory sockeye that never left Redfish Lake. There they survived through brutal winters with limited food resources and grew into adults -- smaller than their ocean-going relatives -- and produced offspring.

Some adventurous percentage of those offspring, however, made the risky journey to the food-rich ocean. The result, biologists say, is that the current fish are genetic descendants of the sockeye that first reached the 6,800-foot elevation lake in the Stanley Basin after the last ice age. The population represents the longest distance traveled to the highest elevation of any sockeye salmon run.

The run was listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act in 1991. That kicked off a hatchery program that at first had only a handful of returning fish to propagate the species. The program received a big boost last fall with the opening of the Springfield Fish Hatchery in eastern Idaho.

The 200,000 juvenile salmon, called smolts, produced at the hatchery will double the number of sockeye released into the system this spring. By this time next year the hatchery aims to be at full production with about a million eggs, Heindel said.

Wild fish are also increasing. Ultimately, Heindel said, the recovery plan is to have 1,000 or more fish spawning in Redfish Lake for multiple generations, and at least 500 spawning in one of four other lakes in the basin. About 2,000 adult sockeye, a combination of wild and hatchery fish, are in Redfish Lake this year. They typically start spawning in early October.

Fall Chinook traveling up the Snake River are a different story.

In 1992, Snake River Chinook were listed as threatened under the federal Endangered Species Act. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration asked the tribes to curtail their fishing activity, setting up a potential battle between the ESA and tribal treaty rights.

"We were prepared to go to court to fight the battle," says Becky Johnson, director of fish production for the Nez Perce Tribe. "But instead of going to court, the tribes proposed a hatchery plan to supplement wild populations."

Started in mid-90s, the Nez Perce Tribal hatchery program, in collaboration with Oregon, Washington and Idaho fish and wildlife agencies, has paid careful attention to the genetic stock to minimize the risk of weakening wild populations, a common criticism of typical hatchery operations.

The hatcheries have introduced young fish into tributaries above the Lower Granite dam, farthest upstream of the four Snake River main-stem dams. As these fish return to spawn, their offspring add to the formerly depleted Snake River stocks.

"I'm optimistic," Johnson said. "I think that things can line up well, for instance if you have good outmigration conditions, good ocean conditions and good river conditions as the fish come in."

"The fall Chinook is a good example of what can happen," she said. "We went from 78 fish in 1990, to last year's 50,000 adults. This year, we predict more than 50,000 adults and we project 27,000 of those will be natural-origin fish."

Johnson said tribal program releases "millions of fish a year, but it's all to mitigate for the dams. About 50 percent of those juveniles make it. ... There's a lot of mortality that occurs between here and the ocean."

"If we didn't have the dams, we wouldn't need the hatchery program up here," she said.

Related Sites:

Preliminary Survival Estimates Memo from Director Richard W. Zabel to Ritchie Graves

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum