forum

library

tutorial

contact

The Great Salmon Debate

by Mary Carmichael & Karen SpringenHealth & Lifestyle, Newsweek, October 28, 2002

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

The Great Salmon Debateby Mary Carmichael & Karen SpringenHealth & Lifestyle, Newsweek, October 28, 2002 |

When you think about how good salmon really is for you, you have to wonder, why would you ever eat anything else? That, at least, appears to be the premise behind Dr. Nicholas Perricone’s “Nutritional Face-Lift,” the three-day regimen described in his new best seller, “The Perricone Prescription,” which calls for six to nine meals of grilled salmon.

And it is the theory on which Isabel Lamb, a Chicago cosmetics saleswoman and devotee of Perricone’s first book, “The Wrinkle Cure,” has made salmon (baked in the oven or microwaved with “just a teeny-weeny bit of butter”) her lunch choice virtually every single day. She credits this diet with making her skin look so much younger than her real age that she won’t give it out because nobody would believe it. Even Dr. Dean Ornish, the famously stringent health guru, will occasionally let himself go to the extent of having a small helping of poached salmon. But then why does Nicole Cordan, 36, of Seattle, who bikes to work and doesn’t eat red meat, look on the fish with utter suspicion? Because chances are the salmon on the plate, underneath its frizzle of dandelion greens and verjus reduction, is nothing like the familiar star of a thousand nature documentaries, heroically flapping up a pristine river to spawn. Instead, it is likely to be the product of an industrial-agricultural system not that different from the one that produced the steak on the next table.

And it is the theory on which Isabel Lamb, a Chicago cosmetics saleswoman and devotee of Perricone’s first book, “The Wrinkle Cure,” has made salmon (baked in the oven or microwaved with “just a teeny-weeny bit of butter”) her lunch choice virtually every single day. She credits this diet with making her skin look so much younger than her real age that she won’t give it out because nobody would believe it. Even Dr. Dean Ornish, the famously stringent health guru, will occasionally let himself go to the extent of having a small helping of poached salmon. But then why does Nicole Cordan, 36, of Seattle, who bikes to work and doesn’t eat red meat, look on the fish with utter suspicion? Because chances are the salmon on the plate, underneath its frizzle of dandelion greens and verjus reduction, is nothing like the familiar star of a thousand nature documentaries, heroically flapping up a pristine river to spawn. Instead, it is likely to be the product of an industrial-agricultural system not that different from the one that produced the steak on the next table.

Cordan, the policy director of Save Our Wild Salmon, is in the anomalous position of fighting what most nutritionists view as one of the few positive trends in American eating habits over the last decade—an increase averaging roughly 20 percent a year in the consumption of salmon, now the third most popular seafood in America behind tuna and shrimp. The boom has been fueled in part by an expansion of salmon farming, which made fresh fish available year-round. Surprisingly, it is canned salmon, the raw ingredient of school-lunch salmon croquettes, that is always wild; the filet you buy at the fish market or the restaurant is usually farmed. “Alaska” salmon is wild; in the United States, fresh “Atlantic” salmon—the name refers to the species, not the fish’s origin—is generally farm raised. (Most farmed salmon sold in America is imported; Canada, Norway, Chile and Britain are the major producers.) But the trend has engendered a backlash by critics who charge that salmon farms are bad for the environment, bad for fishermen—and bad for the people who eat the fish.

‘Radiant’ Skin

Even people who don’t like salmon know by now that it contains omega-3 fatty acids, which are believed to protect against cardiovascular disease and cancer. It was Perricone, though, who elevated another boring piece of nutrition news into a full-blown craze by asserting that omega-3’s can get rid of wrinkles, something he discovered himself years ago when he ate a large salmon dinner and woke up the next day with skin that looked “absolutely radiant.” This is a claim that dermatologists without best-selling books regard with skepticism. “Salmon and other fish, as well as some plants, supply oils that are useful for skin health,” Dennis West, director of dermatopharmacology at Northwestern University, agrees. “I don’t think I would take it as far as clinically reversing a wrinkle.”

If your face really matters to you, Perricone says, you should go to the trouble of finding wild salmon, which he says has two to three times as much omega-3 as farmed fish, higher levels of a potent antioxidant called astaxanthin and less fat. Kevin Bright, operations manager at Cypress Island Salmon Farm near Anacortes, Wash., concedes that farmed salmon are fattier, but, he says, consumers prefer it that way. On the other hand, farmed salmon would be the color of halibut without the addition of a synthetic dye to their feed, which farmers calibrate from a chart to achieve the desired degree of pinkness. There’s no evidence it poses a health risk, but, says Cordan, “who wants to be eating dye?” Dr. Joseph Hibbeln, a researcher at the National Institutes of Health, doesn’t think the differences, while real, are worth worrying about in a country where people still eat an average of just over two pounds of salmon a year, compared with 63 pounds of beef: “It’s better than a hot dog.”

Meanwhile, chefs have discovered that if you cook salmon with enough butter, you can charge almost as much for it as a lamb chop. Alfred Portale, the chef-owner of New York’s esteemed Gotham Bar and Grill, says salmon sales have consistently risen during his 18 years in the kitchen; as an entree choice on his $20.02 prix-fixe lunch, it outsells pasta, the other option, by two to one. Marcus Samuelsson of Aquavit, New York’s only high-end Swedish restaurant, notes that “even people who don’t eat other fish eat salmon.” Like Portale, he cooks with farmed salmon, but uses the wild Alaskan product, when he can get it, for his gravlax, cured and smoked recipes.

Meanwhile, chefs have discovered that if you cook salmon with enough butter, you can charge almost as much for it as a lamb chop. Alfred Portale, the chef-owner of New York’s esteemed Gotham Bar and Grill, says salmon sales have consistently risen during his 18 years in the kitchen; as an entree choice on his $20.02 prix-fixe lunch, it outsells pasta, the other option, by two to one. Marcus Samuelsson of Aquavit, New York’s only high-end Swedish restaurant, notes that “even people who don’t eat other fish eat salmon.” Like Portale, he cooks with farmed salmon, but uses the wild Alaskan product, when he can get it, for his gravlax, cured and smoked recipes.

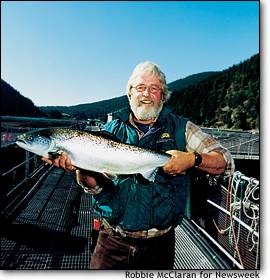

But, Portale notes, he can buy farmed salmon for about $3 a pound, less than a third the price of a good piece of wild fish. That’s one reason salmon farms are prohibited in Alaska, where fishermen blame the farms for undercutting their price. The fishermen have also found allies, somewhat unexpectedly, among environmentalists, including the Audubon Society, which has added farmed salmon to a list of species to avoid. A large fish farm may have more than 2 million 10- to 12-pound fish in net pens covering several hundred acres. Salmon produce a lot of waste, which can build up and combine with uneaten feed into a bacteria-breeding layer on the seabed. The unnatural population densities in the pens can result in epidemics, which could spread to the wild stock. And the fish themselves have been known to escape and interbreed with local populations, with potentially harmful consequences.

Recently the industry has begun to address many of these concerns. Preventive antibiotics, once routinely added to feed, have been largely discontinued; instead, fish are inoculated against common diseases while they are still in hatcheries. Pens can be left fallow for part of the year to allow the waste to disperse. A visit to the Cypress Island farm suggests that, pound for pound, raising salmon is not noticeably worse for the environment than, say, cattle ranching. “There’s a lot of money tied up in these fish,” says Bright. “A bad environment is bad for us.” The Atlantic salmon grown here cannot interbreed with the local Pacific species, and escapees are usually found with empty bellies, suggesting they’re unlikely to survive for long on their own. And if they don’t get rid of all your wrinkles, well, there’s always cold cream.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum