forum

library

tutorial

contact

Climate Change Poses Threat

to Northwest Electricity

by Staff

Washington Examiner, May 16, 2014

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Climate Change Poses Threat

by Staff

|

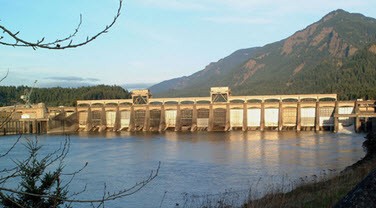

BONNEVILLE DAM, Ore. -- The snowpack along the Columbia River Basin isn't what it used to be, and that's creating problems for the Bonneville Power Administration.

BONNEVILLE DAM, Ore. -- The snowpack along the Columbia River Basin isn't what it used to be, and that's creating problems for the Bonneville Power Administration.

"Average hasn't really been average," Michael Hansen, a Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) spokesman, said of the federal utility's water levels during an interview at the administration's Portland office.

Hydropower is a major presence in the Northwest, as is BPA, which provides one-third of the region with electricity. The Energy Department has big plans for hydropower. Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz announced last month that the agency identified 65 gigawatts of undeveloped potential and that it hopes to double U.S. hydropower capacity by 2030.

But hydropower is looking different than it ever has because of climate change.

Warmer weather has shifted the peak runoff period for BPA a month earlier, from April through August to March through July. Snowpacks are lighter. Rainfall is heavier. Water levels will be lower year round, even as temperatures rise.

This particular mid-May day may be a testament to that. It's nearly 90 degrees Fahrenheit and sunny at the Bonneville Lock and Dam, some 40 miles east of Portland, a city more known for its mist and overcast skies. The chinook salmon run is just about ending, but shad is coming. This annual lull is at least typical.

In recent and future Augusts, when power demand usually spikes, BPA is looking at far fewer resources to draw upon than in previous years. The utility, which produces 7,000 megawatts of hydropower -- enough to power about 5.25 million homes -- in dry years, failed to meet its electricity obligations in 2010.

The faster-melting snowpack, combined with precipitation that used to be snow falling instead as rain, has at times overwhelmed BPA's dams. The utility simply doesn't have the reservoirs to bank all that water flowing into the upper reaches of the Columbia River Basin.

That presents a conundrum for the Energy Department, as the agency must marshal whatever forces of carbon-free energy it can to meet President Obama's goal of cutting greenhouse gas emissions 17 percent below 2005 levels by the end of the decade. As such, the department is assessing how climate change affects water resources.

"The problem hasn't gone away," Moniz said at a recent Washington event. "These uncertainties affect long-term capital planning horizons, which again could threaten our goal of doubling."

The Bonneville Power Administration anticipates that Pacific Northwest temperatures will rise between one and three degrees Fahrenheit from 2010 through 2039, and two to five degrees between 2030 and 2059. It already has experienced precipitation and water flow changes, and is looking into forecasting models to better track those developments.

"If we continue to see extreme change in climate, we'd have to adapt infrastructure or do things differently," said Andy Traylor, fisheries research coordinator at the Bonneville Dam.

Traylor pointed to heavy flooding in May and June 2011 that pushed water levels so high that the dam's two powerhouses were running at full capacity. It had to let much of that water spill out.

On top of power generation, climate change also has posed threats to fish and wildlife management -- BPA spends more than $600 million annually on such programs -- and flood control at federal dams.

During the 2011 floods, juvenile fish died from gas bubble trauma, a product of the vented water combining with gases. The spill water rushing out of the dam also complicated the journey adult fish must make through the dam, Traylor said.

Flood management is a growing concern throughout the federal dam system, said Michael Coffey, a spokeswoman with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers whose district runs from the Pacific Northwest all the way to St. Louis.

That climate change, because of changing water flows, had put pressure on storage reservoirs and increased the risk of winter flooding has been under discussion at the federal level for years. A 2008 BPA white paper on climate change, for example, cited a report from three years earlier that noted the development.

That issue was clear in May 2011 in the drought-prone Missouri River Basin, which was suddenly beset by major flooding, Coffey said.

Coffey said the region encountered an "unprecedented" confluence of high mountain snowpack -- the National Weather Service put it at 212 percent more than average in the Rocky Mountains -- with high plains snowpack and roughly one year's worth of rain during the second half of May alone in the upper basin. All six federal dams had to release record amounts water to prevent overflow, posing flooding threats to nearby towns.

That happened shortly after a tornado leveled Joplin, Mo., while others raged through Alabama, a hurricane threatened the Gulf Coast and the Puget Sound was flooding, only complicating matters.

Coffey wouldn't go as far as to say all those events occurring at the same time was a direct result of climate change, though she did note that an Obama executive order now requires the Army Corps to consider climate change in all its decisions.

"We've not seen that many disasters occurring within months of each other," Coffey said about May 2011. "We were running out of people to send."

Related Sites:

View the vintage films from BPA online.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum