forum

library

tutorial

contact

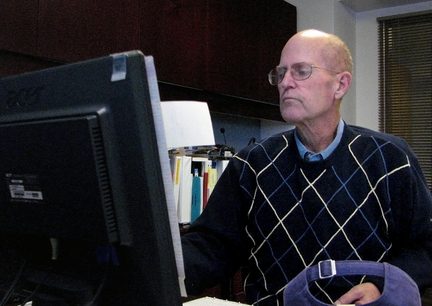

Tim Weaver, Yakama Tribes'

Salmon Champion, says His Goodbyes

by Matthew PreuschThe Oregonian, January 1, 2010

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Tim Weaver, Yakama Tribes'

by Matthew Preusch |

His words crackled a bit over the speakerphone, but when Tim Weaver spoke to the packed federal courtroom, everyone listened.

His words crackled a bit over the speakerphone, but when Tim Weaver spoke to the packed federal courtroom, everyone listened.

The lawyer for the Yakama tribes has spent nearly four decades fighting over salmon. Many people in Judge James Redden's court for the most recent hearing on the Northwest's signature fish recognized that Weaver knew as much as anyone about salmon and the laws that relate to them.

What most also knew is that Weaver was dying.

"This is kind of a goodbye, your honor," came Weaver's voice. "This is the last time I'm going to appear in this court."

Judge Redden, who has spent years grilling lawyers such as Weaver about how to keep salmon from going extinct, visibly softened. The legal arguments paused.

"You've been a friend for a long time, Tim," Redden said.

Those were tender words from a judge on the bench to a lawyer arguing before him, especially a lawyer who has been described as a fireplug, bulldog and other, less-printable terms. Weaver's opponents and allies in the court followed the judge's farewell with their own.

Then Weaver hung up, and the arguments continued.

Weaver, 65, has terminal colon cancer. He's expected to live another two months, maybe three. When he dies, the Northwest will lose one of its foremost legal experts on salmon, a walking library on how tribes' rights relate to that endangered and sacred fish.

"You can tell that everybody in that room -- all of the other lawyers -- have a great response to Tim," Redden said. "He says what the law is, and everyone agrees."

When fish managers sit down to divvy up the year's run of Columbia River salmon, or dam managers decide how much water to divert around power-producing turbines, they are likely playing by rules that Weaver had a hand in negotiating or litigating.

"He's an historic figure, really," Redden said.

What's more, Redden and others say, the courtrooms, backroom negotiations and post-litigation bull sessions will be a little less lively without Weaver, known as much for his turns of phrase as acute legal skills.

"He's such a personality," said Lynn Hatcher, who directs salmon recovery in much of the Columbia Basin for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. "People just gravitate to him."

The colon cancer Weaver thought he'd whipped over a decade ago has returned. He officially retired Friday.

As Weaver himself might quip, he's sort of like a one-legged man in a butt-kicking contest. He can't win.

But he has plenty of victories to look back on.

Advocate for tribes

Weaver grew up in Ellensburg, Wash., the great-grandson of wheat farmers who homesteaded a tributary of the Yakima River when you could still pull salmon from central Washington creeks with a pitchfork.

After graduating from the University of Washington and Willamette University's law school, he moved to Yakima with his wife, Gail, his high-school sweetheart. They have two sons, 35 and 39.

This fall and winter, federal officials, lawyers and judges have been making pilgrimages to Weaver's office overlooking the snow-covered Yakima Valley to say goodbye, maybe share one last laugh over an old war story.

In 1971, Weaver took a job representing the Yakama tribes so he could live where he could fish and hunt when not in the office or courthouse.

Back then, portions of tribal council meetings were still held in the native language. Weaver's legal training didn't prepare him for the nuances of representing his Native American clients. But he was a quick study, and his sense of justice has made him a tireless advocate for the tribe.

"I grew up in a family of sportsmen, and I had the understanding that the Indians were taking all the fish," Weaver said. "It took me about two months to figure out that was wrong."

In the course of Weaver's career, the fight about salmon has gone from who gets to catch how many fish to whether the fish are going to survive at all.

When he started his practice, his clients, the Yakama tribes, had no fisheries program. Now their fish department has about 180 full- and part-time employees, and tribal leaders have a seat at the table with entrenched powers in the basin, namely the Bonneville Power Administration.

They can largely thank Weaver, who is not a tribal member, for that.

"I've had a lot of fun beating up the BPA in the 9th Circuit (Court of Appeals)," Weaver said. "And I softened them up enough that they wanted to take a seat at the table."

Salmon are central to the tribes' religion and their diet. And Weaver has spent decades making sure the Yakama have access to salmon.

He's become a consigliere to tribal leaders, Yakama or otherwise, on regional and national issues, but also the guy they could call for personal legal matters.

"He's really been an unwavering advocate for the tribes and the fish," said Lorraine Bodi, senior salmon adviser for the BPA, who first met Weaver in the late 1970s when she was an attorney for the National Marine Fisheries Service. "It can't have been easy when he first started."

His first big case for the tribes began when he took over the lawsuit Settler v. Lameer, from his mentor and law partner, James Hovis.

"At the time, things were really jumping in the fish business," Weaver said. People were being arrested. There were protests. It was a time when tribes were asserting their rights and embracing their culture, proudly wearing long braids.

"Jim's philosophy was to put you in the pond to see if you could swim," Weaver recalled.

A it turned out, Weaver was a fine swimmer.

He argued the case successfully all the way to the 9th Circuit, which ruled in 1974 for the first time that tribes could enforce their fishing laws outside the boundaries of their reservations.

"I'm still proud of that," he said.

Fighter and negotiator

Though he's not afraid to go to court -- he's appeared before the U.S. Supreme Court twice -- he's known for his willingness to negotiate, as well.

"Most people are either feisty fighters or collaborators," said the BPA's Bodi. "Tim can switch gears."

His toughness helped him play two positions -- linebacker and offensive lineman -- for Ellensburg High School's football team, though he's just 5 feet 6 inches tall.

"When I first came to work here, I immediately starting hearing about Tim Weaver, Tim Weaver," said Steve Parker, head of Yakama fisheries since 1986. "I was expecting someone about 8 feet tall. I was about half right."

Cancer has shrunk Weaver. Though his blue eyes are clear, his handshake strong and his mind sharp, he's down to 130 pounds from 195. His gap-toothed grin is set in a less-rounded face.

Judges and lawyers describe how Weaver used that grin, and the occasional off-color phrase, to lubricate contentious negotiations or ease the tensions in a courtroom.

"For instance, when the court starts, you stand up and look to the other attorney," Redden said. "And he says, 'Why isn't you don't ever have a shotgun when you need one.' That's his way of saying, 'Good morning, counselor.'"

Redden first met Weaver when the judge was Oregon's attorney general, representing the state and fighting the tribe in a long-running litigation over divvying up the catch of salmon called U.S. v Oregon.

In that case, Judge Robert Belloni ruled that Northwest states needed to make sure enough fish reached tribes' historic fishing areas upriver, and a subsequent ruling by Belloni set the tribes' share of the annual runs at half of the total catch.

It started the tribes on a path to a place of prominence in salmon management. But the catch was still fought over every year in court. And Weaver, working with attorneys from other tribes, was at the forefront of advocating tribal interests.

"When he spoke, I listened very carefully, because he knew what he was talking about," said U.S. District Court Judge Malcolm M. Marsh, who handled the case for 14 years beginning in 1987.

Motivated by his belief in tribes' treaty rights, Weaver used the law to subvert the "well-entrenched status quo," he once wrote. The law, he said, gives his clients power not commensurate with their wealth or numbers.

When Weaver dies, the tribes will hold a traditional Seven Drum ceremony in the Winter Lodge in Toppenish, a rare honor for a nontribal member.

Weaver's planned the whole thing out. That's one nice thing about seeing death coming: You can set things in order, say your goodbyes.

"I've certainly gotten a lot of laudatory comments," Weaver said. "And I tell these folks, 'Boy, that's nice, but I wish you would have told me earlier.'"

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum