forum

library

tutorial

contact

Dam Removal:

Too Little, Too Late for Salmon?

by Margot Higgins

Environmental News Network, November 3, 2000

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Dam Removal:

by Margot Higgins

|

Dam breaching may not be enough

to reel salmon and steelhead back

from the brink of extinction,

according to a controversial study

published in today's issue of the

journal Science.

Dam breaching may not be enough

to reel salmon and steelhead back

from the brink of extinction,

according to a controversial study

published in today's issue of the

journal Science.

Wild salmon populations on the Snake River have plummeted to less than 10 percent of their original range over the past four decades. Eight species of salmon and steelhead that use the Columbia and Snake rivers as migration corridors between the ocean and their upriver spawning grounds are listed under the Endangered Species Act.

In July the National Marine Fisheries Service released a long-awaited plan to save endangered salmon populations by restoring fish habitat, overhauling hatcheries, limiting harvest and improving river flow. The plan, which did not call for the immediate removal of dams, received heavy criticism from the conservation community.

Using a matrix model, which provides a mathematical description of the salmon life cycle, NMFS researchers have returned with a report that says the best options for salmon recovery may be within the first year of life.

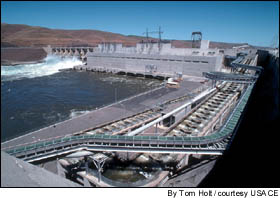

While the authors agree that the construction of four dams on the lower Snake River during the 1960s and '70s "altered salmon spawning habitat, elevated smolt and adult migration mortality and contributed to severe declines of Snake River salmon populations," they argue that other recovery options should be considered.

"We did the study to synthesize information on the stage-specific mortality of salmon and to explore the opportunities for reversing salmon declines by improving survival while the fish were migrating from their birthplace to the ocean," said Peter Kareiva, a senior ecologist for the Northwest region of the National Marine Fisheries Service and lead author of the study. "Science is only part of the (dam removal) debate. Since there are many sources of risk for salmon, the question for public policy-makers may involve examining priorities. Where do we get the greatest benefits for salmon per unit of societal cost?"

Efforts to mitigate mortality associated with dams such as the artificial transportation of salmon around dams have worked to a certain extent, the study notes.

According to Kareiva, there are many more potential ways to increase the first year survival of Snake River salmon and steelhead. Those measures include reducing water pollution, lowering water temperatures and not stocking streams with non-native trout.

"I think these other options simply haven't gotten as much attention as the dam-breaching option," said co-author of the study Michelle Marvier, a biology professor at Santa Clara University. "I think that is the biggest contribution of our work ... we're trying to look at the whole picture. The fact that these salmon face many different threats is not new, people have realized this all along, but there has generally been a myopic focus on the dams. We've tried to place the dams in the context of the whole salmon life cycle. When we do this, we find that fairly small reductions in mortality occurring during the first year and in the estuary could have a large impact."

But favoring first-year recovery strategies over dam removal sounds an alarm in the conservation community, which contends that the majority of salmon mortality occurs after the first year of life. Conservationists claim the NMFS continues to downplay the importance of dam removal by underestimating dam-related salmon mortality.

"A model is only as accurate as the assumptions that go into it," said Scott Bosse, a fisheries biologist at Idaho Rivers United. "This study assumes there is little to no mortality associated with the hydrosystem ... It was conducted by two authors that work for NMFS. This is an in-house process that is subject to very little peer review."

According to Bosse, there is scant proof that egg-to-smolt survival, which occurs during the first year of life, has decreased since the four lower Snake River dams were constructed. Most scientific evidence points to a major decrease in smolt-to-adult survival, which occurs in the migration corridor and in ocean and estuary habitat, he said.

Since there is little scientific data on the survival within estuary and ocean habitat, conservationists say recovery efforts should target the migration corridor, which has been greatly impacted by the four lower Snake River dams.

Bosse points to a study conducted by the Plan for Analyzing and Testing Hypotheses, a 25-member group of biologists, engineers and statisticians representing federal entities, states and tribes, that compared upriver stocks of salmon to downriver socks.

"If the problem was in the ocean or the estuary, both populations would have been

in trouble," Bosse said. "There has been a major difference in the survival of upriver

versus downriver stocks over the last 30 years. The only difference for the Idaho

(upriver) stocks is that they have to go through four more dams. That is the

migratory corridor. That is the smolt-to-adult stage of salmon life."

"If the problem was in the ocean or the estuary, both populations would have been

in trouble," Bosse said. "There has been a major difference in the survival of upriver

versus downriver stocks over the last 30 years. The only difference for the Idaho

(upriver) stocks is that they have to go through four more dams. That is the

migratory corridor. That is the smolt-to-adult stage of salmon life."

Environmentalists point to a February 1999 report by the Independent Scientific Advisory Board, which oversees Columbia basin salmon recovery efforts. The board criticized the U.S. Army Corps for barging the vast majority of juvenile salmon. "It is impossible to reconcile a maximum transport approach to salmon recovery with protection of the remaining diversity of salmon and steelhead populations in the Snake River basin," the report notes.

"It is easy to juggle the numbers to make a particular point," said salmon activist Scott Levy, director and producer of the documentary film RedFish BlueFish. "The authors say that if the estuary and early ocean mortality is reduced by 9 percent that the populations will increase by 10 percent each year. The 'modest improvements' to estuary habitat, noted in the report, would actually require an improvement of over 600 percent in estuarine survival."

Ultimately, salmon recovery might depend on dam removal and several other recovery efforts, conservationists claim.

"Science is only part of the debate for public policy-makers who want to consider the societal cost of losing those dams, but societal cost is not considered in the Endangered Species Act," Levy said. "How will wildlife managers respond if it can be shown that society benefits from dam removal? The list of improvements (to salmon recovery) goes on with recommendations of everything possible short of dam removal, but will these second-place actions together be enough to recover Idaho's salmon and steelhead?"

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum