the film

forum

library

tutorial

contact

|

|

Will Governors' Pledge to Seek 'Collaborative Framework'

Change Trajectory of Columbia Basin Salmon Recovery?

by Bill Crampton

Columbia Basin Bulletin, November 25, 2020

|

The Council is directed to assure an adequate, efficient, economical, and reliable power supply

while protecting, mitigating, and enhancing fish and wildlife affected by hydropower dams.

There is a lot of talk now about finding a new way to coordinate and improve Columbia Basin salmon recovery. A diverse group of river users, utilities and environmentalists is calling on Northwest governors to lead the way in finding collaborative solutions to recover Columbia/Snake River Basin salmon and steelhead populations listed under the federal Endangered Species Act.

There is a lot of talk now about finding a new way to coordinate and improve Columbia Basin salmon recovery. A diverse group of river users, utilities and environmentalists is calling on Northwest governors to lead the way in finding collaborative solutions to recover Columbia/Snake River Basin salmon and steelhead populations listed under the federal Endangered Species Act.

The group called on the governors and Northwest congressional delegation "to foster a new dialogue with all sovereigns and constituents" to develop a strategic plan to recover the fish.

It's nothing new. Back in the day, when the Northwest was first coming to grips with the reality of basin salmon and steelhead being listed under the ESA, then-Oregon Gov. John Kitzhaber said, "The Columbia River is our own answer to the Balkans. It is controlled in various fashions by two nations, four states and 13 sovereign tribes."

"We must create a new forum of state, federal and tribal representatives to decide Columbia River issues," said a frustrated Oregon governor in a October, 1997 speech. "This forum may be a modification of the existing Northwest Regional Power Planning Council, or it may be a new entity. In any event, it must include participation of the four states, tribal interests and the federal government -- and it must have real authority to make decisions on the allocation of resources and the coordination of activities in the Columbia River Basin."

In other words, to be successful a new forum must reduce the Balkanization plaguing salmon recovery.

It didn't used to be so complicated. Before the listings river governance was largely a matter of three operating agencies -- Bonneville Power Administration, Army Corps of Engineers, and Bureau of Reclamation -- coordinating power production and flood control. Salmon recovery could be summed up in two words: Hatcheries, Barging.

Management of this salmon-saving strategy was relatively simple. Federal agencies and Congress worked together in routinely doling out millions of dollars a year to build and operate high-output hatcheries, with most facilities located below Bonneville Dam. Farther upstream the Corps at Lower Snake River and McNary dams collected as many juvenile hatchery and wild fish as possible (up to 90 percent some years) and moved them by barge and truck downstream, presumably from degraded, lethal habitat.

It didn't work. Traditional methods of artificial production and transportation could not sustain, much less recover, populations of wild salmon.

As the fish decline continued throughout the 1980s, the Northwest Power Planning Council -- created by the 1980 Northwest Power Act to balance hydropower with fish and wildlife protection -- attempted to craft "integrated" recovery plans to be implemented by state and federal agencies and tribes. This half-hearted effort to use "subbasin planning" as a way to achieve the Council's goal of "doubling the fish runs" dissipated in a mist of bureaucratic and political failure. Battles over reservoir drawdowns, flows and spill continued at a stalemate pace.

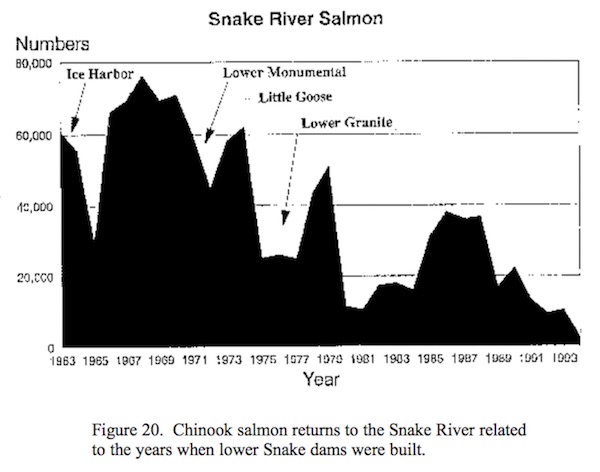

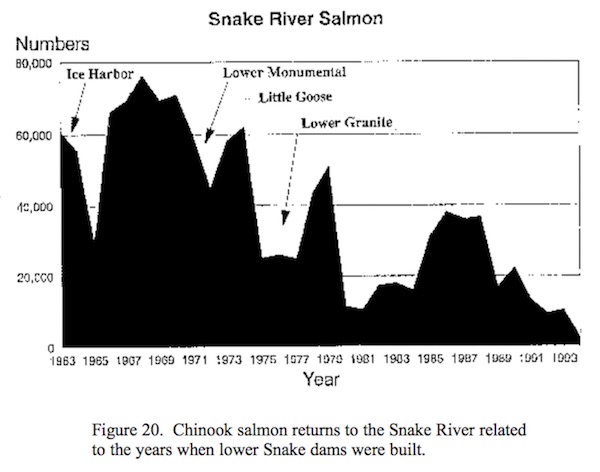

By 1990, 80 percent of Basin salmon were artificially produced. Depending on the year and species, 60 to 90 percent of juveniles originating above McNary Dam were being collected and transported. Hydropower, harvest, poor hatchery practices and habitat degradation from the Rocky Mountains to Portland kept smolt-to-adult return rates below sustainability.

Wild salmon headed for extinction. In 1991 only four Snake River sockeye survived to spawn, while spring/summer and fall chinook had declined to less than 0.5 percent of historical numbers.

Salmon advocates gave up on the Council as an effective salmon-saving institution. Instead, tribes and environmental groups petitioned the National Marine Fisheries Service to list Snake River salmon under the ESA. By 1992 NMFS had listed three Snake River stocks as threatened or endangered and declared one Columbia River stock as extinct.

The federal fisheries agency began to work on biological opinions and recovery plans that would make the basin more fish friendly.

Previously a state-driven process through the Council (two members from each Northwest state appointed by governors), salmon recovery in the 1990s shifted to a federal operation. The Council -- chronically disabled by internal disagreements, regional differences and lack of authority to actually force anybody to do anything -- began to lose its place as the top salmon recovery agency.

NMFS' aggressive entry into Basin salmon recovery represented a profound change in institutional arrangements. Federal agencies, state fisheries managers, tribes and environmentalists looked to NMFS to craft and implement recovery plans for Snake River salmon.

But NMFS, no surprise, faced the same conundrum that stymied the Council. Restoration of nearly extinct wild salmon requires coordination and consensus from headwaters habitat to ocean harvest, and from Congress to counties. Yet management was diffuse and consensus elusive.

Therefore, improved "governance" became the stated imperative. Existing institutions and arrangements were considered ineffective. Establishing a new institutional structure adequate for implementing salmon recovery seemed to be a nearly universal sentiment.

After surveying the chaotic nature of Basin salmon governance, NMFS said, "an organization is needed which will assume the task of properly managing the overall Columbia-Snake River Basin an anadromous resources. The intent is that a single organization will be empowered to make final decisions when consensus cannot be obtained."

So for mainstem operations, NMFS created the "Regional Forum" in 1995. In the beginning, NMFS' Regional Administrator Will Stelle managed to get all parties at the same table -- tribes, states, federal agencies, even the (somewhat wary) Council.

But by late 1996, the spirit of cooperation and consensus began to erode. The major mainstem issues at the time -- reservoir drawdowns, flow augmentation, funding, spill for fish and smolt transportation -- divided the parties. In the spring of 1997, the lower Columbia treaty tribes and the state of Montana pulled out of the Regional Forum, leaving it hobbled as a governing body. Environmentalists, too, considered the Forum flawed, largely because of NMFS' continued emphasis on barging during the spring/summer migration season. The notion of a single organization "properly managing" Columbia Basin salmon recovery was dead, never to be revived.

Until today? Well maybe. Sort of.

The four Northwest governors last month signed the "Agreement Between The States Of Oregon,Washington, Idaho,and Montana To Define A Future Collaborative Framework To Analyze And Discuss Key Issues Related To Salmon and Steelhead With The Purpose Of Increasing Overall Abundance."

The agreement stresses that the states will work together "to rebuild Columbia River salmon and steelhead stocks and to advance the goals of the Columbia Basin Partnership Task Force."

The NOAA-led partnership is focused on the recovery of salmon and steelhead listed under the ESA, addressing the biological aspects of the issue -- pretty much the same thing the old, failed 1996 NOAA-led Regional Forum tried to do. But the partnership does have a far wider range of representation sitting at the table.

Yet, just as in 1996, diverse parties are at the partnership table with strong views about restoring fish runs, or preserving intact multiple economic uses of the river. If any "future collaborative framework" can keep together interests who are often at loggerheads -- most often in federal court -- and lead to meaningful steps toward recovering wild fish, well that would be a sea change for salmon. History wouldn't be repeating itself.

Related Sites:

"Columbia Basin Partnership Develops Preliminary Abundance Goals For Salmon, Steelhead," Columbia Basin Bulletin, August 24, 2018

"Connecting Salmon Recovery Efforts: Columbia Basin Partnership Releases Vision Statement, Goals" Columbia Basin Bulletin, July 20, 2018

"NOAA Kicks Off Columbia Basin Partnership Task Force: Can Salmon Recovery Efforts Be Integrated?" Columbia Basin Bulletin, January 27, 2017

"Feds Seeking Nominations For New Salmon/Steelhead 'Columbia Basin Partnership Task Force'" Columbia Basin Bulletin, July 22, 2016

"NOAA Fisheries Forms 'Columbia Basin Partnership' To Provide Collaborative Forum On Salmon/Steelhead" Columbia Basin Bulletin, Oct. 30, 2015

"NOAA Launches 'Situation Assessment' Of Columbia River Basin Salmon, Steelhead Recovery" Columbia Basin Bulletin, Dec. 14, 2012

"Salmon Recovery Assessment: Who Leads The Long-Term Way? A Re-Defined NW Power/Conservation Council?" Columbia Basin Bulletin, Dec. 20, 2013

Bill Crampton Editor, Columbia Basin Bulletin

Will Governors' Pledge to Seek 'Collaborative Framework' Change Trajectory of Columbia Basin Salmon Recovery?

Columbia Basin Bulletin, November 25, 2020

See what you can learn

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum