forum

library

tutorial

contact

Nez Perce Honor 'Warriors'

who Fought for Fishing Rights

by Tim Woodward

The Idaho Statesman, June 9, 2005

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

Nez Perce Honor 'Warriors'

by Tim Woodward

|

'It changed the whole country.

It was the beginning of co-management of fisheries'

RAPID RIVER -- Elmer Crow and Bill Snow swapped jokes Monday beside the river where they came close to trading gunfire 25 years ago.

RAPID RIVER -- Elmer Crow and Bill Snow swapped jokes Monday beside the river where they came close to trading gunfire 25 years ago.

The occasion was the 25th anniversary of a standoff over the tribe's right to fish for salmon in its homeland. The confrontation, one of the most intense in recent Idaho history, came close to bloodshed and is sometimes referred to as the "Second Nez Perce War."

Members of the tribe held the commemoration to honor those who took part and because they want Idahoans to remember their battle to exercise the fishing rights guaranteed in their Treaty of 1855 with the U.S. government.

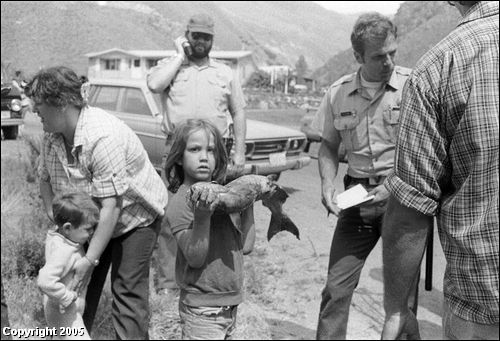

Concerned over declining returns of salmon to the Rapid River hatchery, the state banned fishing for salmon in the summer of 1980. Crow and 31 other members of the tribe defied the ban by fishing anyway. Law enforcement officers were prepared to use deadly force to stop them; the fishermen vowed to fight to the death to preserve their treaty rights. Respective arsenals included clubs, knives, rifles and shotguns.

Snow, now retired, was an Idaho Fish and Game officer at the time.

"It could have been wicked," he said.

"The state had snipers up on the hill ready to shoot us," Crow told a crowd of about 200 at the commemoration. "Unbeknownst to them, we had snipers on the hill behind their snipers."

"It was hard times," Wilfred Scott, then tribal chairman, added. "I think we had more firepower here than we have in Iraq today."

At the heart of the confrontation was one of the smallest salmon returns ever at the Rapid River hatchery. The Idaho Department of Fish and Game ordered fishing closed, a ban members of the tribe saw as an infringement on their treaty rights and way of life. Salmon are an important element in the tribe's culture and traditional spirituality. Nez Perce leaders had restricted fishing to weekends, imposed a limit on the number of fish taken per family and maintained that its practices weren't to blame for the low return.

"We knew we weren't the reason the fish were being wiped out," said Virgil Holt, then a 29-year-old fisherman and now chairman of the Nez Perce Tribe's Fish and Wildlife Commission. "It was the dams and the management that were hurting the fish runs. We weren't responsible for either."

The Rapid River hatchery was built in 1964 to compensate for salmon runs lost to Idaho Power Co., dams on the Snake River.

Bloodshed was avoided when law enforcement officers opted to use citations rather than bullets.

"If a person on either side had done something crazy, Rapid River would have run red," Holt said. "There were some scuffles and clubbings, but that was about the size of it. We were ready to die if we had to. Instead, we got tickets."

Sonny Bybee was among those ticketed. He was jailed twice in Grangeville and released on bail within a few hours both times.

"Then I went fishing," he said.

Monday's commemoration was a far cry from the tensions that existed 25 years ago. Law officers and members of the tribe chatted amiably and exchanged gifts. Members of the Umatilla and Warm Springs tribes attended in support of the Nez Perce. Spiritual leader Horace Axtell gave an invocation entirely in the threatened Nez Perce language. The mountains where snipers once lay in wait rang with the sounds of Native American singing and drumming.

Monday's commemoration was a far cry from the tensions that existed 25 years ago. Law officers and members of the tribe chatted amiably and exchanged gifts. Members of the Umatilla and Warm Springs tribes attended in support of the Nez Perce. Spiritual leader Horace Axtell gave an invocation entirely in the threatened Nez Perce language. The mountains where snipers once lay in wait rang with the sounds of Native American singing and drumming.

Six of the Nez Perce fishermen have died since 1980, but 14 journeyed to Rapid River to be honored along with descendants of the original 32.

"This is part of our heritage, part of our spiritual being," Crow said. "We're here to honor those warriors who stood their ground."

Though the confrontation itself is history, some of the factors that led to it remain. The state and tribe continue to have differences over licensing for steelhead fishing in the Clearwater River, approaches to hatchery, wolf and grizzly bear management.

"I thought we were right then, and I still think so," Snow said. "But I respected the Nez Perce people for standing up for their treaty rights. And I respected the Fish and Game officers for doing what they believed in."

Crow respectfully disagreed.

"What happened here 25 years ago didn't just change Nez Perce country," he said. "It changed the whole country. It was the beginning of co-management of fisheries. Our Nez Perce fisheries department is a good example. It started with three people. Now we have 260."

Today, the state and tribe both decide how many fish will be taken on Rapid River. With returns lower than expected so far this year, according to tribal fisheries manager Dave Johnson, the number allowed for the tribe and general recreationalists has been set at 1,300 each. That's down from 7,000 each last year, he said. An estimated 6,000 fish are expected to return this year.

At this time of year in 1980, only about 600 adult fish had returned to the hatchery.

The "Second Nez Perce War" ended peacefully in 1982. Illegal fishing charges were dismissed when Idaho District Judge George Reinhardt ruled that the tribe's treaties -- another in 1863 affirmed its fishing rights -- gave its members the right to fish in their ancestral streams regardless of the state's actions.

"It was scary here 25 years ago with all those guns around," Linda Crow, Elmer's wife, said. "We were all worried, but the men were doing what they felt they had to do. And they made a difference."

Aaron Penney remembers coming to Rapid River as a boy, one year after the treaty rights challenge. "Watching my dad fish, just the way I'm fishing now," he says. "Fishing's always been in my family."

Many of Philip Johnnie Jr.'s uncles were involved in the fishing rights conflict 25 years ago. "Every year I come to fish. I remember our warriors who sacrificed their lives so we can fish," he says, raising his fist in memory of those who have died in subsequent years. "I'm here to represent them -- who were representing me (back then)."

The NimiipuuThe Nez Perce call themselves Nimiipuu, which means the "real people" or "we the people." The tribe got the name "Nez Perce" through an interpreter with the 1805 Lewis and Clark expedition. The French Canadians interpreted the name as "pierced nose," even though this cultural practice was not common among the Nez Perce.

The tribe once occupied more than 17 million acres of what is now Idaho, Oregon and Washington. Its original homeland included most of the Clearwater, Tucannon, Grande Ronde, Imnaha and Salmon river drainages and much of the Snake River Basin. Today, the tribe's reservation consists of 750,000 acres, 13 percent of which is owned by the tribe.

- Members: About 3,000

- Headquarters: Lapwai

- Land and waters

Treaty rights

In 1855, Nez Perce tribal leaders signed a treaty with the U.S. government presented by Washington Territorial Gov. Isaac Stevens that handed over title to millions of acres of tribal lands to the government. In exchange, the Nez Perce were promised payments and allowed to keep 7.5 million acres. More important, the tribe was allowed to continue hunting, fishing and gathering berries where they had traditionally.

The treaty granted:

In 1974, U.S. District Court Judge George Boldt decided in favor of the tribes and guaranteed them half of the fish caught off reservations. Many opposed the ruling and made an appeal. Finally, in 1979, the case was heard and upheld before the Supreme Court of the United States.

- "The exclusive right of taking fish in all the streams where running through or bordering said reservation is further secured to said Indians: as also the right of taking fish at all usual and accustomed places in common with citizens of the territory."

- In the 1970s, 27 tribal groups brought a lawsuit to federal court, claiming the 1855 treaty had been violated.

Dam promises

- In 1958, Idaho Power Co. began building Oxbow and Brownlee dams, two of the three Hells Canyon dams. The license for the dams required the company to build a system to get salmon up and down the river through the dams so anglers, including tribal fishermen, could continue to catch salmon. Thousands of fish died when the system didn't work and eventually Idaho Power offered to build and pay for hatcheries to offset the losses of habitat.

- Rapid River Hatchery was built in 1964 and Idaho Power is required to release 3 million salmon smolts annually into the Snake and Salmon rivers. The spring chinook raised at the hatchery are from stocks that had lived above the Hells Canyon dams.

Idaho Statesman reporter Rocky Barker contributed to this report.

Nez Perce Honor 'Warriors' who Fought for Fishing Rights

The Idaho Statesman, June 14, 2005

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum