forum

library

tutorial

contact

To Recover Salmon Populations,

We Need to Think Bigger

by Kurt Miller

Portland Business Journal, March 25, 2022

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

To Recover Salmon Populations,

by Kurt Miller

|

A legitimate case can be made that these (LSR) hydropower projects

are not the limiting factor for sustainable salmon populations.

Four vessels and more than 60 scientists backed by NOAA Fisheries are headed to sea as part of the largest expedition ever to study salmon in the North Pacific Ocean.

Four vessels and more than 60 scientists backed by NOAA Fisheries are headed to sea as part of the largest expedition ever to study salmon in the North Pacific Ocean.

Their goal is to better understand extreme climate variability in the ocean and its impact on Pacific salmon. The expedition will focus on an area of salmon research that remains woefully sparse and underfunded, yet critical for recovery efforts.

Notably, this expedition has a mere $10 million in funding. It's a drop in the ocean compared to the billions of dollars invested in freshwater habitat projects and research over the years. The fact is, even though salmon spend most of their lives in the ocean, very little is known about where they migrate to during the marine phase or where the highest degree of mortality occurs once they reach the ocean.

We believe this context around salmon recovery is vitally important. Likely, you're already aware salmon were nearly fished into extinction by European settlers and their descendants, well before the first federal dam was built on the Columbia River in 1938.

Still, many people blame dams -- especially the lower Snake River dams -- for hampering salmon recovery. Such is the case with Miles Johnson and Les Welsh's recent op-ed.

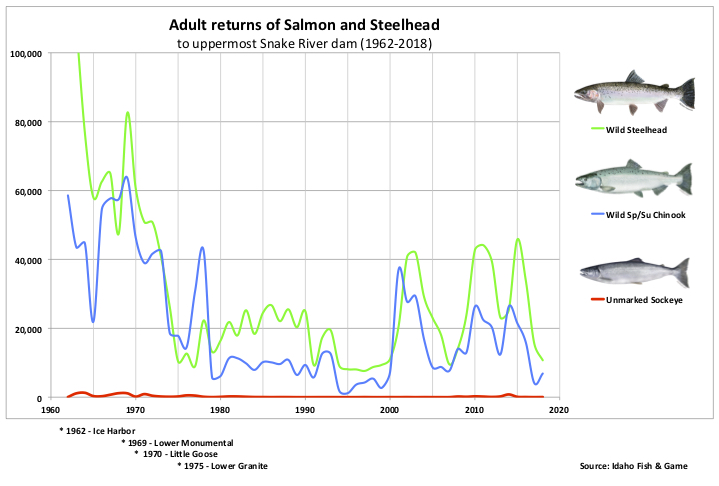

However, that blame may be misplaced. A 2020 peer-reviewed study showed Chinook salmon populations up and down the West Coast of North America have seen average survival rate declines of 65% over the past 50 years, whether salmon originate from free-flowing rivers or rivers with dams.

The study noted survival rates for Snake River Chinook are consistent with Puget Sound-area rivers, the free-flowing Fraser River in Canada, and even nearly-pristine rivers in southeast Alaska. This time period coincides with what the UN's IPCC refers to as a 50-year period of unabated ocean warming.

Last year, NOAA Fisheries published a peer-reviewed study which predicted key Chinook populations may go functionally extinct by 2060 if ocean conditions continue to increase at their current trajectory. The study also noted ocean warming poses a much greater threat than river temperatures to the viability of salmon.

That isn't to say that mitigating the impacts of the hydropower system isn't important. Over $2 billion in improvements have been made to the fish passage systems at the lower Columbia and lower Snake dams over the past two decades. These improvements have resulted in impressive gains in juvenile salmon survival. At this point, a legitimate case can be made that these hydropower projects are not the limiting factor for sustainable salmon populations.

We recognize those who want free-flowing rivers have good intentions, but there are major societal implications, not the least of which is losing a vital source of zero-carbon electricity during a climate crisis that imperils salmon. The lower Snake River dams, by themselves, produce almost as much electricity as the output from all of the wind turbines in Oregon -- combined.

Before taking the drastic action of removing modernized, highly beneficial dams, it's important to be certain about the trade-offs. If we want to help salmon, we must more adequately invest in unveiling the mysteries of salmon in the marine environment where they spend most of their lives.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum