forum

library

tutorial

contact

What is Obama's Plan for the

Northwest's Imperiled Salmon?

by Matthew PreuschThe Oregonian, September 13, 2009

|

the film forum library tutorial contact |

|

What is Obama's Plan for the

by Matthew Preusch |

More than a century ago, the Columbia River and its tributaries so roiled with wild salmon it was said that in places you could walk across the water on their backs.

More than a century ago, the Columbia River and its tributaries so roiled with wild salmon it was said that in places you could walk across the water on their backs.

No more. Canneries, mining, cities and many dams later, it's all changed. Generations have argued about how to bring the fish back from the edge of extinction. More than $1 billion a year is spent trying, but there are no more fish returning to the river now than there were two decades ago.

What's holding the fish back?

On Tuesday, the Obama administration will reveal how it thinks we can have the many hydroelectric dams that bring us cheap power, navigation routes and flood control without pushing salmon past the brink.

But dams aren't the only suspect. A changing climate, warmer water, competition from nonnative fish, outdated hatchery operations -- all have been blamed at one time or another for the decline of the Northwest's signature fish.

Many hope the new administration -- with Oregon ecologist Jane Lubchenco leading its top fisheries agency -- will hasten a productive change in the nation's most expensive species recovery conundrum.

"The phase we're stuck in now is the dithering phase, and it's a difficult phase because we are going to have to reallocate resources. And that takes political courage," said Michele DeHart, director of the federally funded Fish Passage Center.

The administration has until Tuesday to explain to U.S. District Court Judge James Redden how its plan to offset the damage done to fish from federal power-producing dams differs substantially from the approach employed by the Bush administration -- an approach that Redden has attacked, in his court, as inadequate.

Redden outright rejected previous plans, called biological opinions, in 2000 and 2004.

The administration Tuesday will announce its revisions to a plan released last year.

That plan won broad support among most Northwest tribes and states, key parties to repairing the Columbia's salmon runs. Tribes alone have treaty rights to the fish.

"There's clearly been an evolution in the government's (Endangered Species Act)-based plan," said John Ogan, an attorney for the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs. "It was developed with our input, collaboratively, with really unprecedented public access."

Even so, the state of Oregon, the Nez Perce Tribe and conservation groups continue to fight in court, arguing the federal government's approach is illegal and doesn't do enough for fish.

Based on interviews with those familiar with the Obama administration's discussions, Tuesday's unveiling will not dramatically alter the approach we've known from the previous administration.

"I'm not anticipating an earth shift," said Ed Bowles, fish division administrator for the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Two weeks ago, federal officials showed their plan to opponents at a secret meeting in Portland. While details are scant, it will likely address specific requests Redden made of the U.S. government earlier this year:

But the key task for Redden is to decide whether federal government's latest approach satisfies requirements of the Endangered Species Act.

"The sense of the (biological opinion) is it's the best available science, which is what the ESA calls for," said Lorraine Bodi, senior policy adviser for fish and wildlife for the Bonneville Power Administration.

Doing what the ESA calls for, however, is getting more expensive all the time -- and with mixed results.

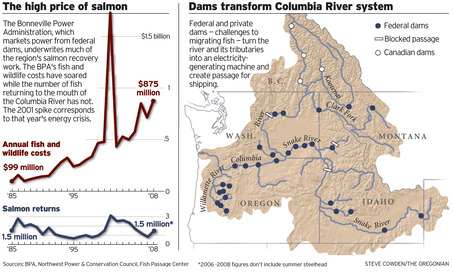

The BPA, which markets power from 31 federal dams, provides the bulk of salmon recovery funds in the Columbia Basin and says it spent $875 million last year on fish and wildlife costs, mostly for salmon.

That figure is controversial. It includes the cost of power sales the BPA couldn't make because of limits to dam operations forced by helping salmon. And it includes power the agency had to buy from out of the region to make up for power lost from its fish program.

The total spent by the agency since 1978 is about $12 billion. That spending shows up in your power bill. About 15 percent, or $11, of the average Nortwesterner's monthly electricity charges goes towards salmon, according to the Northwest Power and Conservation Council, which develops the regional strategy to balance fish and power needs.

Over 20 years ago, the council set a goal of doubling the number of salmon and steelhead entering the mouth of the Columbia River from the 2.5 million it was then to 5 million, still only a third to a half of historic runs, estimated at 10 to 15 million.

But the region is no closer to that goal now. And there is still no monitoring program in place to tell whether all the money we're spending and work we're doing is helping.

"The only stocks that are showing better numbers are the Sockeye and the Fall Chinook, and that's because we are flooding the system with baby hatchery fish," said Jim Martin, salmon advisor for former Gov. John Kitzhaber.

The prospects for salmon don't look good. Global warming is expected to reduce regional snowpacks, meaning less water in our rivers to carry the salmon to and from the ocean, where they mature.

Increasing human population could continue to erode the habitats of the fish as we build homes, roads and businesses besides the rivers and lakes.

"Fundamentally, salmon need the same things that humans need. So it's a competition, and it's a zero sum game," said Robert Lackey, a former senior fisheries biologist at the Environmental Protection Agency and a professor at Oregon State University.

More recently the council set a deadline for doubling fish runs of 2025, and they are working on developing a uniform monitoring plan for fish across the basin.

But it's anyone's guess when the fish might be healthy enough to come off of the list of endangered species.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association, led by Lubchenco, estimates the fish closest to recovery, mid-Columbia steelhead, might be ready to come off the list in 25 to 50 years. And that's if everything goes as planned.

"There are a lot of ifs," Elizabeth Holmes Gaar, NOAA's regional recovery coordinator for salmon, said. She and others caution it will take time to see the benefits of recent work.

"But if we are aggressive about implementing and taking these steps, I believe we can recover these fish," she said.

learn more on topics covered in the film

see the video

read the script

learn the songs

discussion forum